Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a Contributing Editor of City Journal.

Americans are concerned about crime. In the lead up to the 2022 elections, violent crime was a top issue on voters’ minds. In a recent Politico survey of mayors, half said that public safety was the most pressing issue in their communities.

Though voters’ perceptions of crime don’t always match reality, today they’re not far off. Homicides have risen sharply since 2019, by as much as 30 percent through 2021, and rates have only recently begun ticking down. Motor vehicle theft remains elevated nationwide. And while the pandemic suppressed lots of street crime, criminologists Aaron Chalfin and Maxim Massenkoff have argued that robbery and assault also rose after controlling for the drop in foot traffic.

To this, some retort that while the upticks are real, they are relatively small compared to the 1980s and 1990s when homicide rates were almost double those of today. This is true, but also not the full story. Many major cities have seen record homicide figures. And among young Black men — already most at risk of homicide death — rates are approaching prior peaks.

At the same time, those peaks are not necessarily the right baseline. Even during the pre-pandemic lows, America was a much more violent place than many of our peer countries. Among the countries of the OECD for which I could find data, America has the fourth-highest homicide rate and the fifth-highest serious assault and rape rates. By one estimate, our gun homicide rate is 25 times higher than that of other developed nations. America is much more dangerous than our level of prosperity suggests we should be.

There are lots of popular explanations for this disparity. As Matt has observed, some of it is attributable to the large number of guns we own. Some of it may be cultural or sub-cultural — the persistence of southern honor culture explains part of why that region has a higher homicide rate, e.g.

In a recent Atlantic article, Reihan Salam and I suggested a different perspective: identifying the “root causes” of our comparatively high rates of violence is less important than adequately applying the tools of policy to the problem of controlling violence. The level of violence should be understood primarily as a function of the extent to which state capacity is exerted to stop it. Violence, that is, is a policy choice.

A corollary of this is that reducing violence — to pre-pandemic levels or to the lower levels of other nations — requires the more vigorous exercise of policy. As I argue, below and in a recent Manhattan Institute report, we have in recent years gone the other direction, deprioritizing the criminal justice system and allowing its problems to fester. What is needed instead is a serious investment, one that offers real promise for making America safe.

Our struggling criminal justice system

Some readers might object that America already invests a lot in its criminal justice system. But the numbers tell a more complicated story. Per the Bureau of Economic Analysis, we spend a relatively small share of public dollars — about four percent across all outlays — on police, prisons, and judges. Budget share tells us something about budget priorities. Through the 1980s and 1990s, public safety became a greater focus of the budget process, reflecting concern about high crime rates; it peaked around six percent in 2002. As crime declined, the budget share receded, particularly following the Great Recession.

Such aggregate figures obscure another challenge for funding criminal justice: how decentralized the system is. There are over 18,000 police departments in the United States, compared to 43 in the U.K. and 19 in Germany. We have thousands of prosecutors’ offices and tens of thousands of trial court judges. This diffusion means both that local governments pay for a larger share of the criminal justice system than for other budget functions and that limited super-local dollars are not targeted as efficiently as possible. Perhaps as a result, poorer and less white jurisdictions have less police protection than richer and whiter ones.

More generally, the decline in funding share since the Great Recession has mirrored a number of declines in the capacity of the criminal justice system. If the level of violence is a function of how well the system is running, then we should not be surprised that we have seen violence spike in recent years.

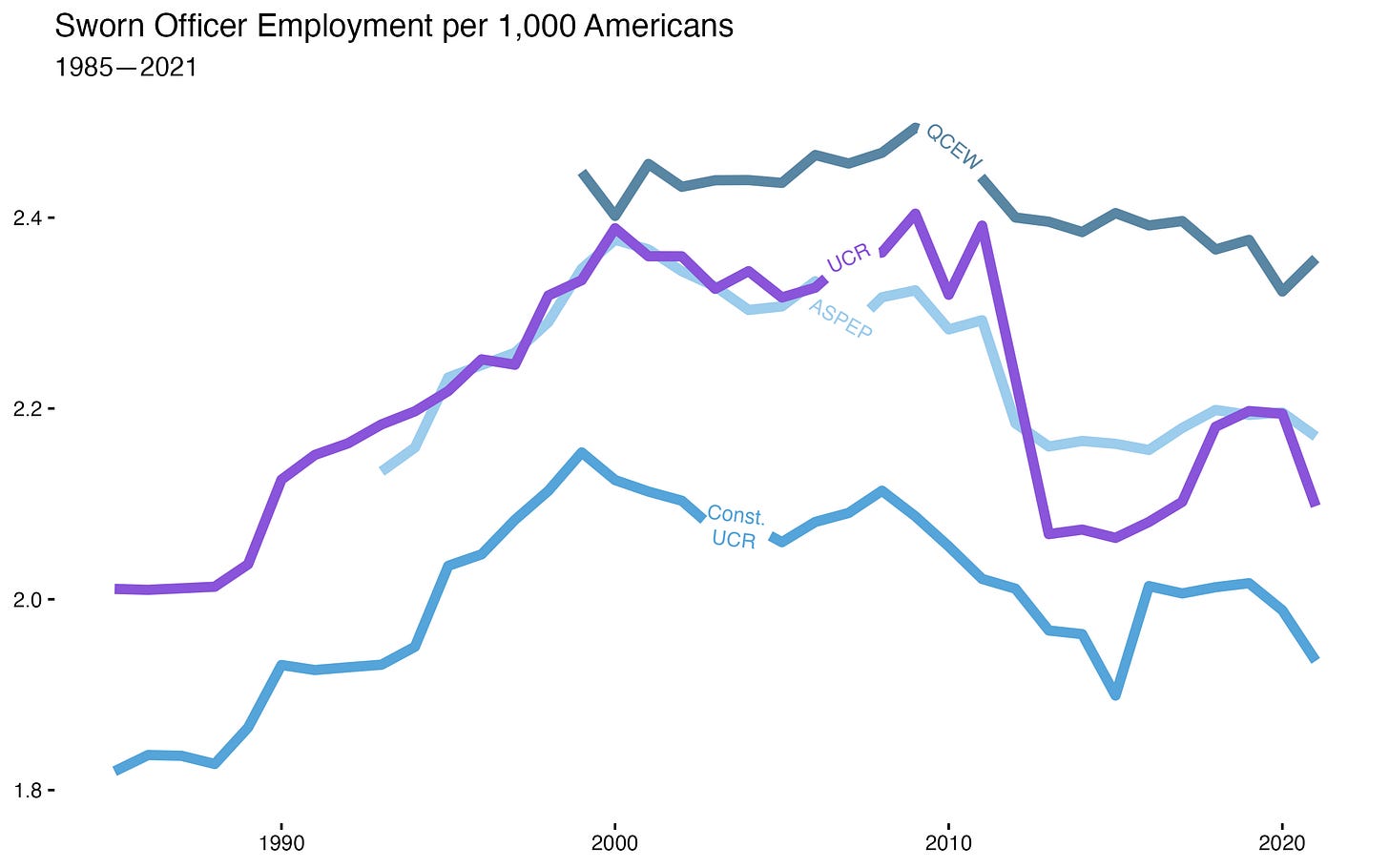

Take, for example, policing. The above figure charts four different measures of police employment rates (for source details, see the report). While they provide different estimates of the level, they all indicate the same basic trend: since the Great Recession, the ratio of police to population has declined significantly. Given the overwhelming evidence that police reduce crime, all else equal, we should expect more crime from this trend.

American prisons and jails have long had deep problems: endemic gang violence, widespread drug use, and frequent staff abuse. But they’ve gotten worse in recent years, as suicide, overdose, and homicide deaths have all risen even as populations have declined. Our courts are also running much more slowly, the National Center for State Courts has found. This slowdown contributes to jail overcrowding, reduces the swiftness essential to deterrence, and endangers defendants’ constitutional right to a speedy trial.

We’re even doing less to understand our criminal justice system. The FBI’s recent transition to a new system for collecting crime data has left us with almost no idea how crime changed in 2021. And even under the old — and far from perfect — system, data were released on a year-plus lag. We spend a pittance on basic scientific research on crime. Funding for the DOJ’s “research, evaluation, and statistics” account — which funds the National Institute of Justice and Bureau of Justice Statistics — has plummeted in recent years. NIJ research funding totaled just $76 million as of the most recent annual report.

We could address these issues. And we could do it at a relatively low price, compared to both current commitments and the truly enormous social costs of crime. In the aforementioned report, I propose a package of modest investments which could put a serious dent in our sky-high rates of violence.

More cops, faster courts, better prisons

The Department of Justice already doles out police hiring grants every year, primarily through the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) office. The office was authorized about $300 million in grants in FY 2023, a dramatic decline in nominal and real terms from the $1.4 billion per year it was first handed in 1995. Supercharging COPS-funded hiring is a proven way to bring crime down.

This isn’t just a guess. Numerous studies have exploited randomness in receipt of COPS grants to investigate how they affect crime. They have consistently found significant crime reduction: a 10% increase in employment reduces violent crime rates by 13% and property crime by 7%, by one estimate.

How much to spend? A very rough estimate is that returning to pre-Great Recession staffing ratios would require about 80,000 new police officers and would run about $10 billion, or $2 billion annually over five years. That’s more than what we currently spend but less than the original outlays adjusted for inflation.

We could maximize benefits by earmarking at least 10 percent of the funding for detectives who, as Matt has noted, are an under-attended way to bring down violence. Congress could also end the requirement1 that half of funds go to small jurisdictions. While spreading the wealth is laudable, the reality is that big cities need more police because they have more crime.

Problems with our detention and court systems merit attention, too. It’s hard to run down why deaths are rising in prisons and jails, but they aren’t rising everywhere. A targeted prison remediation program, combining funding with the threat of federal monitorship or receivership if prisons don’t shape up, could improve prison conditions — which in turn can reduce recidivism.

A faster court system, meanwhile, probably entails some fairly technocratic fixes. In their exhaustive study, the National Center for State Courts found that the fastest courts practiced “active case management,” with the judge taking a deliberate interest in expeditious procedure. A 2019 pilot project in Brooklyn followed similar principles and cut time to disposition by 22 percent. It’s not clear that more money would solve what is ultimately a best practices problem. But the federal government could certainly lead the way by promulgating national standards for efficient case management.

Work smarter, not harsher

Like any policy area, criminal justice involves lots of trade-offs. The harsher your system is, the more false positives you’ll get; the more lenient, the more false negatives. But a smarter criminal justice system reduces the risk of both outcomes, meaning the system can be more effective without also necessarily being more punitive. Investment in criminal justice data and research, in other words, is almost a free lunch — all it costs is money. In the report, I propose bulking up research and statistics funding with an additional $300 million per year.

Some of that money should go to getting better crime data. At the very least, cities need to update their crime records systems to comply with the new data reporting standards — an update they’ve known was coming since 2015. Consider a carrot and stick model: allow states to use any DOJ funding on the upgrade, but also claw back an increasing percentage of their funding each year they fail to comply.

Even then, though, the system will be slow and therefore not very helpful. One solution is an idea first outlined by crime analyst Jeff Asher: create a “sentinel cities” program, under which major cities report monthly, or even weekly, crime data to the federal government. These figures, Asher and his colleague Rob Arthur have shown, tend to predict national crime figures pretty well. It would also be cheap, because many cities already track and publish crime data, albeit in a disorganized way.

The bulk of new funding, though, should go to seriously expanding NIJ’s research and development capacity. Experimental criminology is still a relatively young field — it wasn’t until the 1990s, for example, that we got decent evidence of the effect of cops on crime. Better research could yield large, durable crime-reduction gains and permit more experimentation with unproven but promising approaches like violence interruption. One way to lean into this orientation would be to give the NIJ its own flexible, highly experimental ARPA equivalent, much like the NIH’s new ARPA-H.

Upgrading the criminal justice system should be — and has been — a bipartisan priority

Violence is a large and persistent problem in the United States. But it seems like there is little appetite for a significant investment in bringing it down. On the right, fiscal conservatism makes any spending hike unpopular, while the contemporary left is more skeptical of the criminal justice system than ever. This coincidence of (dis)interests has driven the criminal justice conversation for the past decade and contributed to our system’s current disrepair.

But this isn’t how things have always been. Historically the federal government has responded to surges in crime with significant investments in the criminal justice system, often on a bipartisan basis. In response to growing organized crime, the Roosevelt administration sought and Congress authorized a slew of modernizing bills.2 In 1968, a wave of national disorder and violence produced the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act, which authorized hundreds of millions for training and hiring police officers. And when violent crime was peaking, Congress met President Bill Clinton’s call for 100,000 police officers with the “single largest piece of federal criminal justice legislation in U.S. history,” the 1994 crime bill.

All three of these measures were passed with bipartisan support, two overwhelmingly so.3 They were also the work of Democratic White Houses and Democratic majorities in Congress. There is no particular reason that the Democrats, with their greater appetite for government spending, cannot co-opt tough-on-crime rhetoric once again — particularly because the 1994 bill’s chief architect is now president. Republicans, meanwhile, talk a tough game about the need for law and order. And most conservatives agree that public safety, if nothing else, is a job for the government. Putting their money where their mouth is would be advantageous for the right as well.

Most importantly, though, it would make everyone’s lives better. Crime, especially violent crime, is a serious social ill, the harms of which can last for years or a lifetime. We, as a nation, have too much; we could choose to have far less. Why shouldn’t we?

See 34 U.S.C.§ 10381(h), which incorporates 34 U.S.C. § 10261(a)(11)(B).

From the O’Reilly article, linked above: “Congress approved without even taking a record vote six bills requested by Cummings and drafted by the Justice Department.”

You can find 1968 vote totals here, and read more about 1994 (a tighter vote, but still passed on a bipartisan basis) here.

"The level of violence should be understood primarily as a function of the extent to which state capacity is exerted to stop it. Violence, that is, is a policy choice."

I endorse many of your proposals -- collect more data, speed up the court system, prioritize spending in cities, etc. But the quotation and the framing reek of mid-60s hubris. E.g.:

"The level of illegal drug use should be understood primarily as a function of the extent to which state capacity is exerted to stop it. Drug use, that is, is a policy choice."

"The level of communist influence in Indochina should be understood primarily as a function of the extent to which state capacity is exerted to stop it. Letting Hanoi win, that is, is a policy choice."

This attitude that we can simply apply "state power" in ever-increasing quantities in order to win a War On X has proven to be a bad guide to policy in the past.

At the very least, policy should be guided by the understanding that "as a function" will mean "as a linear function" only for the easiest parts of the curve, and may mean "as a logarithmic function" or even "as an asymptotic function" for most of the curve. Reducing violence by a third (e.g.) may be a "policy choice" that requires non-infinite resources; eliminating violence is probably not one.

I'm asking for more incrementalism in the approach and the rhetoric -- at least a little bit more.

I appreciate the meta-discourse of this article: A liberal writer gives a conservative writer a platform, and the conservative writer tries to persuade a (presumably) left-leaning audience of his policy agenda, using both data and appeals to liberal concerns (e.g., Black people are disproportionately the victims of crime).