The case for vaccinating chickens

Let's get serious about bird flu

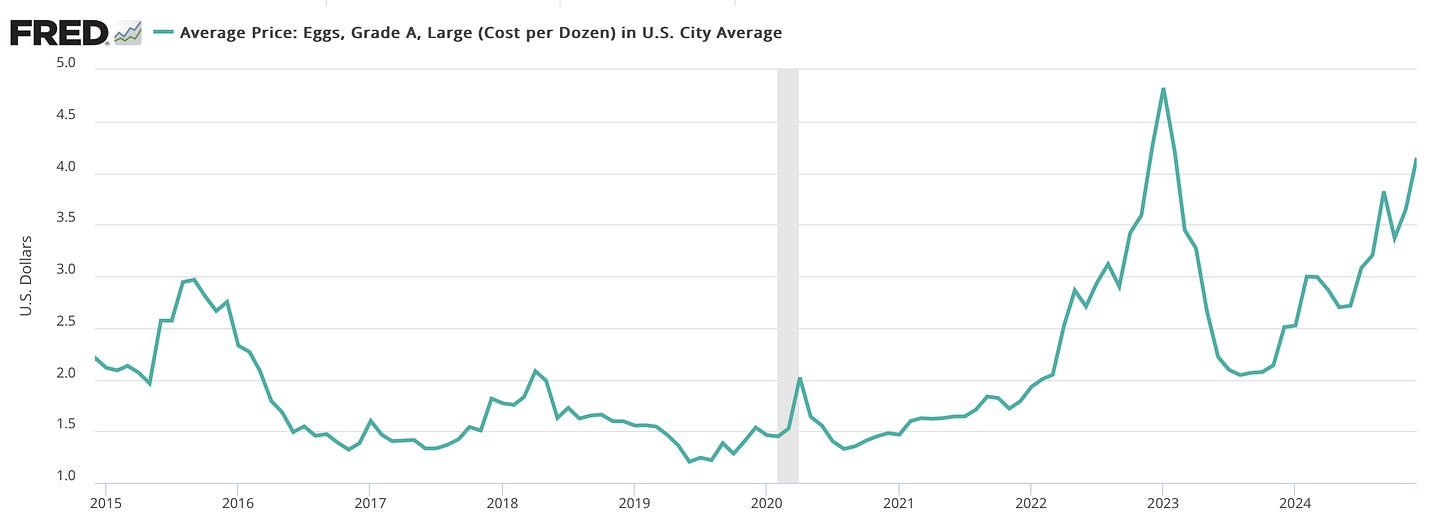

Egg prices soared in 2022, only to crash in 2023 and then pick up again across most of last year. These fluctuations, which are way out of line with historical norms, are not really “inflation” in a macroeconomic sense, but instead represent supply-side shocks to the poultry ecosystem due to the spread of H5N1 influenza among America’s chickens.

This is probably going to get worse.

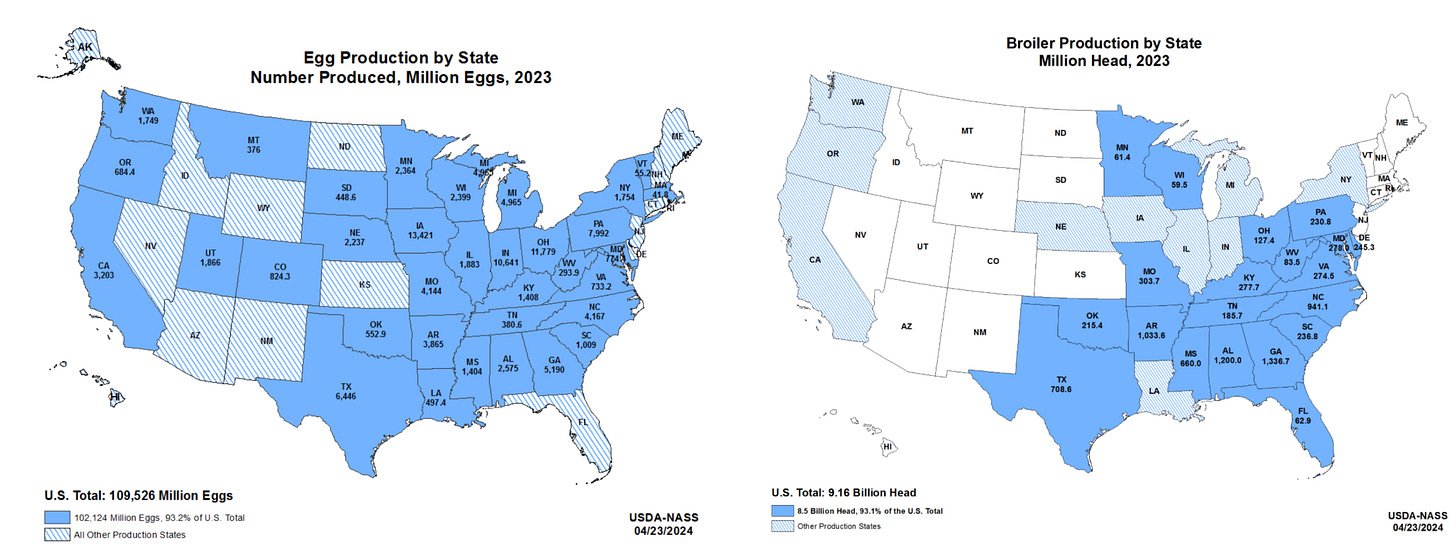

Last Friday, the state of Georgia announced its first case of H5N1 in a commercial poultry operation and has broadly suspended the state’s chicken industry as they do culling and testing of additional flocks. Georgia is responsible for nearly fifteen percent of America’s broiler chickens, plus about five percent of the eggs. We’re looking at potentially very large disruptions to an already turbulent industry.

I think we also need to acknowledge at this point that while the risks to human health from H5N1 appear to remain relatively modest, there’s no good news on the pathogen control front. It keeps spreading to more dairy herds, and we’re not in any meaningful sense on top of the situation. The good news is that we haven’t yet seen human-to-human transmission and also that while the virus is dangerous, it does not appear to be super-deadly.

Still, even if nothing worse happens than spikes in grocery prices, it turns out that spikes in grocery prices are pretty bad and the government should try to address them.

New senator Ruben Gallego pointed out to me over the weekend that during the last great egg price spike, Americans in border states were driving to Mexico to buy eggs and bringing them back home. This is illegal, so please don’t do it; this observation is not financial advice.

Gallego’s point was that H5N1 has not been spiking the Mexican chicken industry because Mexico vaccinates its birds. This has a certain up-front cost, but it also means they don’t need to do flock-wide cullings any time a bird tests positive. Leading a large-scale vaccination campaign (one that the relevant industry stakeholders are skeptical of) doesn’t sound like the kind of thing Donald Trump would do. But unlike in 2017, he’s enjoying a honeymoon period, so I think it’s worth suggesting that this is something the administration might want to look at. The tradeoff is basically more stable domestic prices (and less animal cruelty) offset by the potential reduction of profit opportunities for exporters, and I think any administration that thinks it through will see that stable domestic prices are a win.

Supply shocks and inflation

This seems as good a time as any to address a lingering concern about the relationship between supply shocks and inflation:

Trump advisors last week explained that tariff increases can’t be inflationary, because they impact relative prices not the general price level.

The Biden White House, by contrast, continues to attribute most of the inflation of recent years to supply chain problems rather than demand-side policy.

As a pedant and a guy who’s read some undergraduate macroeconomics textbooks, I prefer Trump’s way of looking at this.

Let’s say the administration levies broad, across-the-board tariffs and we don’t get exchange rate adjustment. Well, everything that Americans buy from abroad will get more expensive. What’s more, lots of domestic producers will raise prices, too. Almost all coffee is imported and will get more expensive thanks to tariffs. But there’s a little bit of coffee grown in Hawaii that’s not subject to tariffs. Those plantation owners are going to take advantage of the tariff situation to raise their prices and reap a windfall. Stuff gets more expensive.

But do we get inflation? Most people only have so much money. If the price of coffee goes up, they might respond by buying less coffee. Whether total coffee spending goes up or down in response to a price hike is actually completely ambiguous. But supposing that demand is relatively inelastic and coffee spending rises, that still implies offsetting cutbacks in spending elsewhere. If you make imported goods expensive enough, you might crash rents since nobody has money left to spend on housing.

And that’s true of supply shocks generally.

During the pandemic, the supply of low-end computer chips was disrupted. This meant that production of new cars took a hit for several months. That caused new car prices to rise, and also spiked the price of used cars — an incident with valuable lessons for housing policy — which a lot of people said contributed to inflation. But why did soaring car prices lead to inflation? Why didn’t people either cut back spending on cars in the face of higher prices, or else shift spending out of other categories into cars leading to offsetting price drops elsewhere? You can’t explain a rise in the overall price level with a rise in the cost of one specific thing. The story isn’t just supply shocks. It’s supply shocks occurring in the context of a situation where most people had extra cash stocked up after cutting back in 2020, where almost everyone was getting extra cash from the American Rescue Plan, and where the Fed’s problematic Flexible Average Inflation Targeting framework meant they weren’t going to try to cut off extra spending at the first sign of inflation.

The supply shocks were real, but supply shocks aren’t a sufficient explanation of inflation.

So narrowly, I think Trump’s team has this right. Raising taxes on imports need not lead to inflation per se. Neither will mass killings of chickens. Or mass removals of agricultural workers. The bad news about all of this is that negative supply shocks are actually worse than inflation. We (re-)learned the lesson recently that voters really, really do not like inflation. But part of why inflation happened is that policymakers were trying to help the economy ride out adverse shocks. They maybe went too far with this. But imagine a world in which the price of chicken and eggs is soaring and there’s also upward pressure on beef and dairy, but policymakers keep a tight lid on the economy to ensure that spiking grocery prices don’t lead to an increase in the average price level. The only way to engineer that is to make sure people are cutting back a lot in other areas — not dining out, not traveling, not buying subscription newsletters — such that prices start to fall.

This is, for most people, going to be strictly worse. The price of eggs is soaring and you can’t get enough shifts at work because demand for your services is collapsing.

That’s a long digression, but the point is that quibbling aside, it’s a really good idea to try to avoid negative shocks to the supply side of the economy rather than spend your time worrying about whether they’re actually inflationary.

The barriers to vaccinating chickens

Jess Craig wrote a great overview of poultry vaccination for Vox last May, and I just want to add one basic observation that’s not in her piece: From the standpoint of the poultry industry, the fact that the current “stamping out” approach to flu control leads to sporadic destruction of flocks is a little bit economically ambiguous.

On the one hand, yes, you might have to kill a bunch of your chickens and lose your investment.

On the other hand, when prices spike due to stamping out, you secure windfall profits — your cost basis hasn’t risen, but the market-clearing price soars.

Factor two is especially important, because in the grand scheme of things, chicken and eggs are pretty cheap. Even when chicken gets expensive, it’s cheaper than beef, for example, so demand is likely to be pretty inelastic in the face of price increases. Because eggs are a thrifty food, it’s the kind of thing where if the price rises, people tend to just pay more, complain, and cut back elsewhere rather than buying less.

Of course, if it’s your chickens that get wiped out, that’s bad for you. But you don’t know ex ante whether it’ll be your chickens that are killed or someone else’s. And the prospect of someone else’s chickens being killed has a meaningful upside for you. Which isn’t to say that poultry farmers are secretly plotting to encourage H5N1; it’s just to underscore that their economic incentive to fight it may be less than you’d think at first blush.

This intersects with Craig’s main point — if we started vaccinating chickens, it would kill our poultry exports:

The biggest sticking point is around trade. The US exported more than $5 billion in poultry meat and products on average every year for the past three years. The USDA enters into trade agreements with each individual country it trades with, explained Upali Galketi Aratchilage, a senior economist at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Each agreement outlines specific biosafety and production requirements that both countries agree to follow. The USDA said, in an email to Vox, that many of those agreements do not allow bird flu vaccination.

The ostensible biosafety concern here is that stamping out ensures you won’t export an infected chicken, whereas with a vaccination based approach, you might export an asymptomatic bird. Today, though, farmers and regulators actually rely on molecular tests, so this is completely outdated. The USDA also cautions that the current vaccination regime “continue[s] to rely on a two‐dose regimen, which can be impractical for distribution to flocks.”

These are real obstacles, but they’re hardly insurmountable. On the first point, you would, in fact, either need to make American chicken exporters take a hit or else take the time to renegotiate various agreements. There’s no good reason we couldn’t renegotiate the agreements, but any time a change is made, there’s the potential for problems. No administration really wants to expend time, effort, and energy on something as picayune as poultry export protocols, and they also don’t want to infuriate the industry.

The alleged logistical problems with the two-dose regimen really just seem like a cost issue. Chickens already get lots of vaccines. But the industry doesn’t see the economic benefits of vaccination as worthwhile, especially given the export complications.

From a public interest standpoint, I think the calculus is flipped. Having more stable chicken prices without the risk of shortages that generate windfall profits for producers would be good. But beyond that, even though the risk of this flu strain becoming a deadly human pandemic seems low, it’s not zero. As we learned during Covid-19, the economic cost of deadly pandemics is really high. Spending modest amounts of money to make unlikely events even less likely is a good deal.

The challenge of time-consistency

Unfortunately, politics is hard.

I find that smart people who get interested in a particular policy issue often wind up becoming intensely frustrated with the political system and the bad politicians and “unelected bureaucrats” who populate it. But I think in practice, these are mostly well-meaning people of above-average ability who are struggling with some pretty fundamental issues.

We all know that “a stitch in time saves nine” and that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” But the basic asymmetry is that while voters care about issues, most of them are only paying attention to a handful of things at a time. And the vast majority of the people paying attention to poultry-related issues at any given time are industry stakeholders who like the way things are going. If you pick a fight with them, you’ll probably lose. If you try to buy them off, you’ll run into the fact that other people who are fired-up about other things don’t understand why you’re wasting time and money on this. If you tell people that a short-term increase in baseline poultry prices is worth it for greater long-term stability, they’re going to tune you out.

There was a brief period when all kinds of people were fired-up about the FDA’s approach to regulating home-based virus tests, because in the spring and summer of 2020, this felt urgent and pressing to them. But within a few months, most of these people were on to arguing about different aspects of the pandemic. And then soon enough, they were done arguing about Covid altogether.

If your efforts at aversion succeed, the problem doesn’t arise, and no one gets credit for solving problems that never arise. One of the things people in my line of work can do, though, is call attention to issues before they become urgent and encourage more long-term thinking. But the shift of more and more attention to social media spaces makes that harder than ever. I’m not sure I have a solution, other than offering a reminder that each of us, as individuals, have some agency regarding what we talk about and click on and subscribe to and write our members of Congress about. We have vaccines that work. We have an example next door of a country where they are used. Whatever anti-vax mania is sweeping the country, I don’t think people are worried about autistic chickens. We could do this if we bothered to care.

"I don't think people are worried about autistic chickens"

absolute banger of a line, a master at work

As someone who works in agriculture, I believe this article undercuts the importance of exports for the U.S. poultry industry. While exports only account for 15-20% of poultry production, they play an outsized role in the value of the bird, as the 15-20% is not distributed evenly across all bird parts.

Americans love to eat chicken wings and chicken breasts, but you can't grow a chicken that's only wings and breasts. Other countries prefer different parts of the bird including legs, dark meat, and "paws" (chicken feet). By exporting those parts of the bird, we limit food waste and create a market for chicken parts that otherwise of little value. Without these export markets bringing value to all parts of the bird, the overall value of producing an individual bird will plummet - and make the parts Americans love (wings and breasts) significantly more expensive as production declines.