Earlier this month I spoke to Andrew Marantz for this laudatory New Yorker piece on the Sunrise Movement. I think his angle made it hard to really fit my point of view in, but speaking with Marantz was an opportunity to gather my own thoughts more clearly and explain both why I’m so critical of Sunrise and why I think this is important.

Before getting into that, though, I want to be clear that I think Sunrise is a symptom rather than a cause of problems: the organization reflects a framework that’s baked into the world of progressive climate philanthropists, and that has generated strategic and tactical failures that predate Sunrise, including the movement to get Barack Obama to stop the Keystone XL pipeline.

And it’s worth stepping back from the debate about specific tactical decisions and bad tweets to examine that underlying framing. This is the way I think the left sees the climate issue:

There is a latent desire among the mass public for sweeping change in general and for sweeping climate-related change in particular.

The main impediment to change is an elite cabal of special interests, most of all the fossil fuel companies, who wield power through campaign contributions and buying ads to distort the media agenda.

Due to the corrupting influence of fossil fuel money, not only do Republicans take bad stances on climate-related issues but so do Democrats, which means highlighting Joe Manchin’s personal financial relationship to the coal industry is crucial to communicating the legislative dynamics at work.

The upshot of this framework is that we need a broad grassroots movement that can push the political system (including corrupt and wayward moderate Democrats) into taking the drastic action the planet needs and the people demand.

And my view is that this is all wrong.

The real world of climate politics

The vast majority of people believe that climate change is a real problem and would like to see politicians and elected officials do something about it.

But popular commitment is fairly shallow for a number of reasons:

Most people are somewhat selfish and somewhat short-sighted, and the worst impacts of climate change occur in the future and afflict other people.

Climate is a global problem and solutions require global coordination, which is inherently difficult and involves players who want to free-ride and also those who worry about others free-riding.

Humans are often arbitrarily averse to change. If you tell people “instead of X you can have Y,” they have a strong tendency to be suspicious that Y is worse than X.

So is the climate issue completely hopeless? Averting 1.5 degrees Celsius of climate change as the world’s governments have formally agreed to probably is hopeless. But largely as a result of policy changes, worst-case climate outcomes have become less likely over time. And there is plenty of scope for further policy breakthroughs. That’s largely not because the mass public is demanding change; it’s because political elites are pretty bought-in on climate as a serious problem.

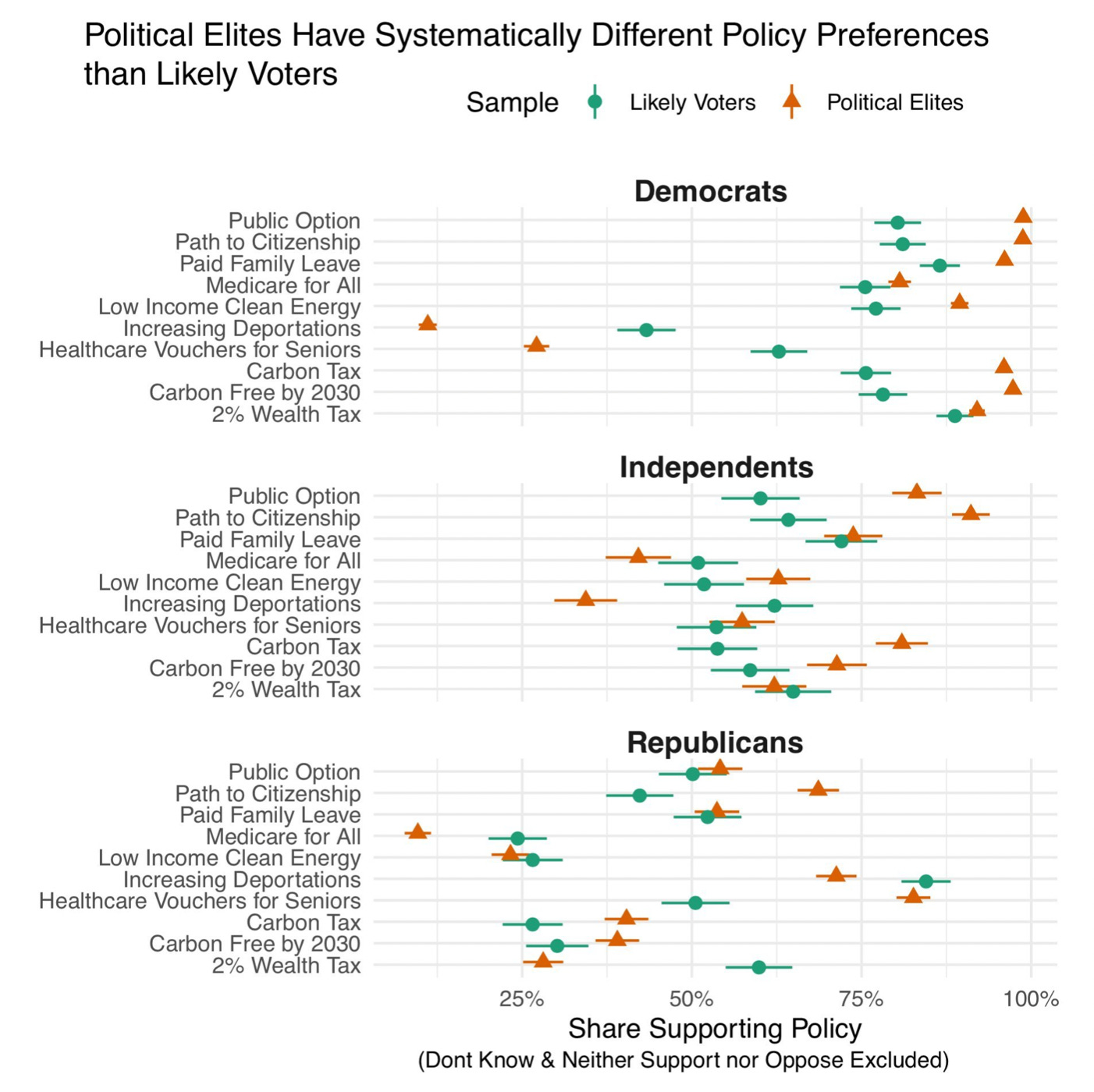

I’ve referenced this Alexander Furnas and Timothy LaPira survey previously, but it’s very interesting. They surveyed a class of “3,500 political elites and public servants” defined to include “thousands of unelected bureaucrats, judges, media pundits, campaign consultants, lobbyists, think tankers, commissioned military officers, lawyers, scientists, and business and nongovernmental organization leaders.” They then segmented the elites into Democrats, Republicans, and independents and compared elite views to those of rank-and-file voters. They found that Democratic elites are systematically more left-wing than rank-and-file Democratic voters. But while Republican elites are more right-wing than GOP voters on most issues, climate change is an important exception.

Independent elites, similarly, are more supportive of aggressive climate policies than are rank-and-file independents.

That is the saving grace of climate politics.

The scientists who say that climate change is a real problem with negative consequences that will compound over time are correct, and they produce arguments and evidence that are persuasive to well-informed people. And elite actors have a somewhat more long-term orientation than the mass public and thus are more attuned to this scientific evidence.

That elite buy-in is why one of Secret Congress’ major actions was to pass an energy bill that included important climate provisions during the lame-duck session in the winter of 2020-21. Same for the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework.

Climate progress is driven by elites

The point is not that low-key bipartisan climate bills are enough or that this level of change is adequate.

But their contents reveal that the progressive theory of climate politics is fundamentally backward — bipartisan dealmaking behind closed doors is not dominated by fossil fuel interests and does not feature moderate Democrats selling out to join with Republicans to promote dirty energy. On the contrary, Democrats consistently prioritize climate in these negotiations and some Republicans are sometimes willing to make concessions.

Consider Elon Musk, who leftists on the internet hate. Why do they hate him? Well, he has an annoying Twitter persona. But more broadly he’s a super-rich guy who — like most other super-rich people — thinks capitalism is good and labor unions and high taxes are bad.

And those are the fundamental organizing blocks of democratic politics — under capitalism, the median income is lower than the mean, so it’s possible to organize electoral majorities in favor of redistribution, and then conservatives organize a coalition that’s capable of blocking that redistribution coalition. A blocking coalition can be against same-sex marriage when being against same-sex marriage is politically useful but drops the issue like a rock as soon as it becomes a vote-losing embarrassment. You can have a clean energy future in which there are lots of rich guys who own companies that make EVs and solar panels and don’t like labor unions or progressive taxation. So climate is something conservative elites are willing to compromise on.

But of course the real key here is Democratic elites.

Everyone is mad at Joe Manchin all the time, and indeed Manchin is not great on climate issues. That being said, he’s not terrible on climate issues either. He’s better than every single Republican, for example. He’s not a hard no on promoting clean energy the way he is on D.C. statehood or banning assault weapons. He has every incentive in the world to say “fuck this, I’m ride or die for fossil fuels” and go full-tilt climate denialist. But he doesn’t.

Of course, most Democratic elites are more progressive than Manchin (and specifically more progressive on the climate topic), and that reflects a broader divide in American society. When Navigator Research helped me look at differences between college graduates and non-college Dems, we saw that college Democrats place more emphasis than their non-college co-partisans on voting rights, the pandemic, “jobs and the economy,” and climate. Non-college Dems care more about Social Security and health care.

In common sense terms, this is good news for climate activism.

If you imagine a policy problem with the same broad structural features as climate, but where elites in both parties were more hostile than the mass electorate and where support was disproportionately concentrated among people without a college degree, it would be totally doomed. The reason the climate has a fighting chance is that people who care about this issue have disproportionate power in the system.

But to fully take advantage of that dynamic, climate activists need a correct analysis of the situation.

Climate advocates should be good allies

The idea of allyship is hot in progressive circles, but it’s typically interpreted to mean that each member of the coalition should vocally support the most extreme demands of every other member of the coalition.

That’s great if you want to assemble a coalition that loses elections constantly.

Instead, climate advocates should acknowledge to themselves that Democrats basically have their backs, and they should try, in turn, to be good allies to them. Activists often like to analogize themselves to the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, but the actual situation they face is completely different. The Democratic Party of 1961 was not on autopilot to prioritize civil rights issues in bipartisan negotiations. Nor was it even clearly the better party on civil rights; the biggest segregationists in Congress were all Democrats. Manchin — bad as he may be on climate — is better than all the Republicans, while in the ‘50s and ‘60s, tons of Republicans were better on civil rights than at least some of the Democrats.

So that thorn-in-the-side, good-trouble model of activism is wholly inappropriate.

Climate philanthropists have invested huge sums of money in sponsoring activist groups that generate lots of bad press for Democrats. The idea is that while bad press helps Republicans win elections and thus damages the climate, the threat of bad press for Democrats forces them to be more aggressive on climate than they otherwise would be. That would make sense if it were genuinely true that corrupt elites are sabotaging popular climate policy, but it’s not true. On the contrary, what we see is that highly ideological elites are more aggressive on climate than their own base wants. Pushing Democrats to be even more aggressive risks harmful electoral backlash. And punishing Democrats for being prudent makes things even worse.

Many millions of dollars have been invested over the years in this style of activism, and if all that money had been piled up and set on fire, we’d be in a better place today.

The folly of back-door carbon pricing

Despite what push polls say, carbon pricing has always been very ugly politically.

I don’t think a carbon tax is a bad idea on the merits or even necessarily something that’s politically impossible. But the circumstances under which it could come to pass are pretty specific and driven by elite dynamics. Back in the mid-aughts, lots of people believed the United States was likely to face some kind of budget deficit crisis in the near future requiring a bipartisan austerity deal along the lines of the one hashed out between George H.W. Bush and congressional Democrats in 1990. In a deal like that, basically all of your options are unpopular, so the fact that a carbon tax is unpopular isn’t necessarily dispositive. And in terms of possible deficit-reduction ideas, Republicans like the carbon tax more than taxing the rich and Democrats like it more than cutting domestic spending, so it works as a compromise.

But in a world where there isn’t an urgent need for austerity, deliberately making people’s energy prices higher is toxic.

What’s weird is that climate activists acknowledged that direct carbon pricing was bad politics, but then wouldn’t acknowledge why it’s bad politics because they were stuck on the idea that the masses yearn for sweeping action on climate change. So they settled on the idea that while passing a bipartisan bill to price the externalities associated with greenhouse gas emissions was too hard, they should try random gambits to kneecap fossil fuel production. So even though blocking the Keystone XL pipeline mostly serves to divert oil to less-safe, train-based modes of transportation, it was a thing the Obama administration had the authority to do, so activists lobbied to do it. They campaigned to get universities to divest from fossil fuel companies. They got Sarah Bloom Raskin to write an op-ed suggesting that the fossil fuel industry should be cut off from the Fed’s emergency lending programs during the pandemic.

The problem with these measures is that to the extent that they are politically viable, it’s because they don’t work. Right now with energy pricing spiking, lots of conservatives are scolding Biden over the Keystone issue. The administration replies, accurately I think, that their actions here don’t meaningfully impact oil supply or gasoline prices. But that’s just to say that they also don’t meaningfully impact CO2 emissions. If they did impact emissions (and the Raskin Plan to force the entire oil and gas industry into liquidation certainly would have), the mechanism would have been through higher prices. But unlike a carbon tax, randomly increasing the price of energy by handicapping production at the source doesn’t generate any revenue.

The only advantage to this form of back door carbon pricing is that it lets activists play games with themselves, keeping fingers crossed that their ideas won’t actually be effective enough to spike prices and generate a backlash.

Sustainable climate politics

In defense of climate philanthropists, the two main good ideas in climate policy — pushing Democrats to invest money in lowering the cost of zero-carbon electricity and keeping the carbon tax alive on the back-burner in the event of a budget crisis — are also things that they are supporting.

But I think the trick is to admit that this really is the strategy. It’s true that there are some specific fights about blocking specific fossil fuel projects that are winnable at least at certain moments in time. But philanthropists have to consider how specific fights relate to the larger battle. If you convince yourself that there’s a hidden majority of climate fanatics, then you can talk yourself into the idea that getting Joe Biden to pledge to stop fracking on public lands was a critical organizing success story. At the end of the day, though, you either think that driving up the cost of energy on a partisan basis is politically viable or you don’t. If you do think it’s viable then you’re mistaken, but the right way to do it would be with a carbon price that generates revenue you can spend on other priorities (this was the Waxman-Markey idea). But if you decide it’s not viable, then you want to just let it go and stop wasting time. If you do that, you can own the energy abundance brand and focus on moving from clean energy R&D to clean energy deployment, making common cause with conservatives where necessary to eliminate regulatory barriers.

None of this is particularly original, but it requires accepting that climate advocacy is an elite-driven effort to foist good ideas on a somewhat indifferent public rather than an effort to mobilize a silent majority against a corrupt elite.

The “we need to make sacrifices” gets “activists” dicks hard way more than it should.

Battery and solar panel prices are falling to the point where folks can be self sufficient in energy, including vehicle charging. A world where the average American comes home and plugs in his F150 Lightning and reads about some revolution in Saudi Arabia or Iran and thinks, “To think we used to worry about that.” Is a wonderful vision you could sell to voters.

As someone whose work is trying to implement decarbonization, one of the things we've been grappling with for the past few years is a complete refusal from the advocates to admit that decarbonization is hard, and that it's hard for legitimate reasons. As you say, the "a shadowy cabal of elites is preventing us from carbon-free utopia" view is predicated on the idea that most people actually want to decarbonize but often there is no ability to admit that decarbonization requires "sweeping climate-related change". Part of this is because we've made most of our progress in the electric sector, in a way that's basically invisible to most people (even allowing for slightly higher electric rates, many regions saw lower growth in electric rates over the same time period due to low gas prices).

But honestly a lot of it is magical thinking, just straight up denialism around the practical realities of what we need to do. I would be overjoyed if I never needed to have another conversation trying to explain why only doing a bunch of 5 kW rooftop solar systems is not going to get us to a zero carbon electric fleet, or "replace your heating system" is just not something most homeowners get excited about under any circumstances, or that drop-in electric replacements for the most popular cars in America are just not available right now, or that actually most people buy used cars! And good luck finding a used EV! I have yet to hear any of the advocates lay out a path for decarbonization that's realistic for suburban Ohio for example. It's incredibly frustrating as a practitioner -- we need to be trying to make this as easy as possible for people, but that starts with admitting that it's hard for real reasons.