Skilled immigration is good

But bad housing policy can ruin anything

Sriram Krishnan, an Indian-born venture capitalist at Andreessen Horowitz who worked with Elon Musk on the Twitter takeover, tweeted shortly after the election that he wants to “unlock skilled immigration.”

About a month later, he was tapped by the Trump administration to serve as an artificial intelligence advisor in the White House, setting off a flurry of discontent among the nativist right. Musk and other members of the newly ascendant right-wing faction of Silicon Valley went to bat for Krishnan personally and for skilled immigration in particular. The ensuing debate largely focused on the H-1B program, which brings a lot of Indian-American computer programmers to the United States, though I think it’s worth noting that Krishnan’s initial tweet did not actually mention this program.

Donald Trump himself also weighed in on the controversy, saying, “I have many H-1B visas on my properties. I’ve been a believer in H-1B. I have used it many times. It’s a great program.” The transition team was not able to identify for journalists which Trump properties employ people on H-1B visas. I’m fairly certain that what Trump actually meant was that his hotels employ people on H-2B visas, which is a totally different program (Trump is older today than Joe Biden was at his inauguration, but when it comes to this kind of memory lapse, he always benefits from the perception that he’s a huge liar who has no idea what he’s talking about). Bernie Sanders also chimed in to say that “Musk is wrong” and the purpose of the H-1B program is “to replace good-paying American jobs with low-wage indentured servants from abroad.”

Interestingly, though, in subsequent discussion, Sanders and Musk both endorsed the same reform to the program: raising the minimum salary floor.

This seems like a good idea to me, broadly speaking, and I’m happy to see both fans and critics of the program to agree to agree on that change. But I think it’s worth discussing the virtues of the current version of the program, not because H-1B is so great, but because the fact that even a badly flawed program is beneficial tells us something important.

The flawed but good H-1B

The initial round of intra-right discourse on this topic was pretty amusing to anyone in the left-of-center camp: A bunch of nativist types were saying predictably racist stuff, and a bunch of right-wing tech guys were shocked (shocked!) to learn there’s racism and xenophobia in the MAGA movement.

But beyond irritable mental gestures, the thing that both H-1B haters and tech industry moguls can agree on is that even though these visas are reserved for people with specialized technical skills, the program design is flawed and they don’t always go to the most talented people. For a company to hire an H-1B worker, the role needs to meet various criteria: a minimum salary, both in absolute terms and relative to the prevailing wage for the job category, and a requirement for specialized skills, among other things. But all the applications that meet the criteria are entered into a lottery, and 85,000 winners are picked at random rather than based on any assessment of merit.

So while many of these visas ends up going to really skilled engineers working at top tech companies, many of them do not. Instead, a reasonably large share end up in the hands of people making high five-figure salaries doing pretty banal IT or accounting work. And a very large share goes to IT outsourcing companies that maintain a small staff in the United States working with clients, but send the majority of their work to India.

This is sort of a dumb system, but it’s worth noting that while it’s dumb, it’s clearly beneficial on net.

Michael Clemens did a study of one of these much-derided Indian “bodyshops” and showed that when an Indian IT firm wins the right to bring an Indian programmer from India to one of their American offices, they increase the employee’s pay by two- to six-fold. The way this works, the company has to want to bring the guest worker over. It’s not like the programmer comes to America and that gives him leverage to demand a higher salary. The worker’s work is just so much more valuable to the outsourcing company if he can be located in the United States that it’s worth paying him dramatically more. That’s a very large productivity increase we’re talking about. It’s true, of course, that the main beneficiaries of the productivity increase are the immigrant himself and his employer. But unless you’re a person who has a strictly zero-sum view of the economy, you have to acknowledge that any time you can see a worker’s productivity double, triple, or even quintuple, something pretty impressive is happening for overall growth.

Of course, in the context of immigration, someone always raises the concern that this benefit to foreign-born wage earners generates downward pressure on native-born wage earners.

But H-1 workers’ earnings are well above the national average, so they can’t be pulling down average wages. If they’re doing anything, they’re reducing inequality by reducing wage dispersion. And for people in the bottom half of the wage distribution, they are pulling up demand — whether that’s in retail or food service or whatever else. Again, this is not to deny that the critics are raising valid points about program design. The point is just that visas for skilled workers are very good, so much so that even a program with design flaws is beneficial.

A broader view of immigration and skills

Handing out a fixed pool of work visas on a random basis is, however, fundamentally pretty dumb.

The simplest improvement we could make would be to raise the minimum salary threshold, which would reduce the number of applications for the 85,000 visas. The salary profile of the recipients would be mechanically higher. Tax revenue would be higher, because that’s how the tax code works. The demand-side benefits of the program would be larger, because we’d have higher-earning workers. This is such a clearly good idea that despite their differing perspectives on the overall merits of H-1B, both Musk and Sanders ended up arguing that we should raise the salary floor.

That said, I do still think the difference in underlying perspective is important.

If you see H-1B as beneficial, then you probably think that we should expand the pool of visas, and if we reform the program to make it more beneficial, you’ll be inclined to say that the case for expansion is even stronger. By contrast, if you think the program is bad, you’ll be inclined to restrict it quantitatively. You might agree that helping the very most talented foreigners come here is good, but that only underscores the case for raising the bar while shrinking the program. And I think that’s a mistake. Basically anyone who moves here for work and is a net contributor of tax dollars is an economic win for the United States. Anyone earning an above-average salary is both a win for growth and for reducing inequality. It’s good to have a meaningful bar for immigrants to clear, but the bar does not need to be particularly high.

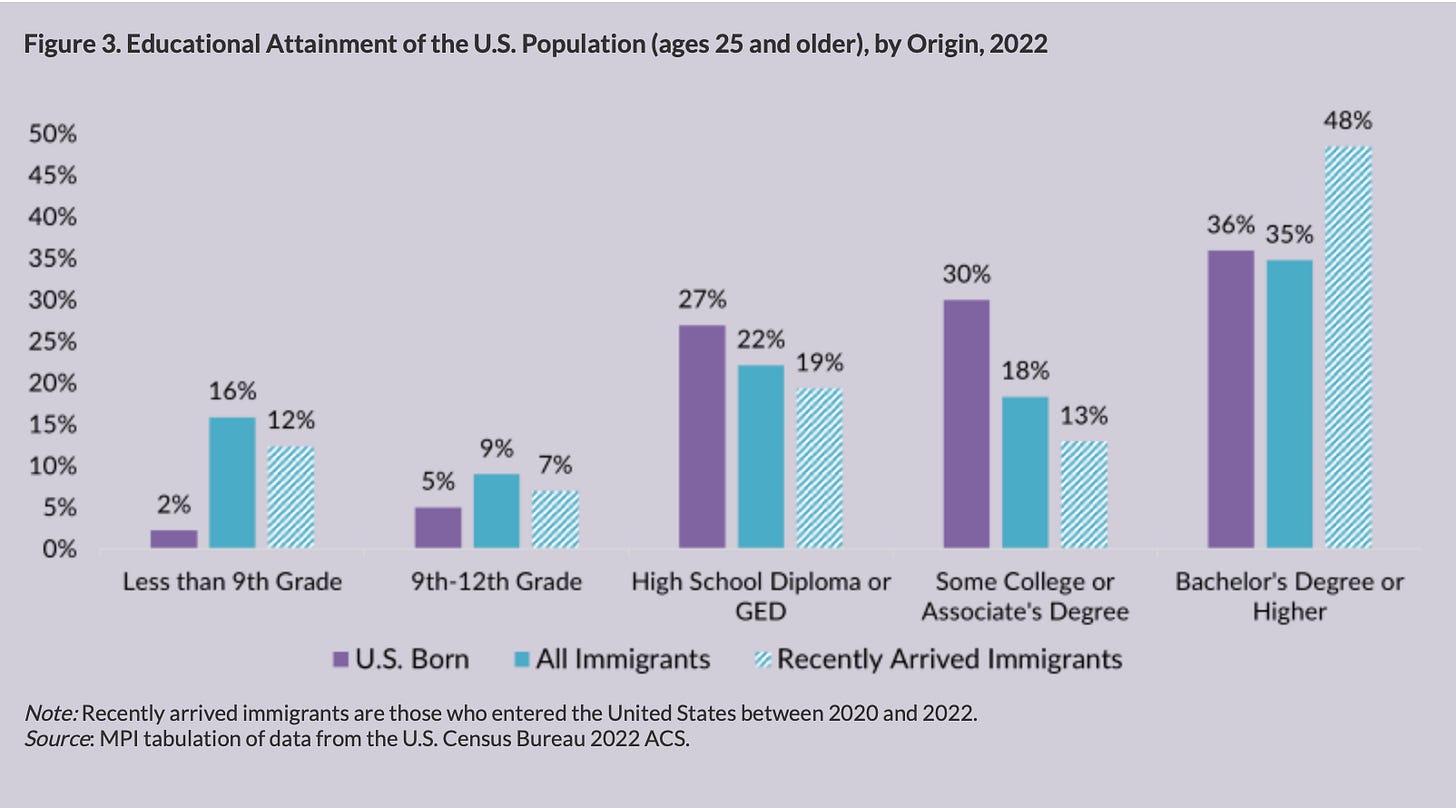

This is one reason why I’m generally pretty complacent about the overall state of legal immigration programs for the United States. Before the huge Biden-era surge in asylum seekers, recently arrived immigrants were, in the aggregate, better educated than native-born Americans.

Even a widely criticized program like the diversity visa lottery ends up admitting a pool of people with a higher skill profile than the population average. Illegal immigration creates a lot of problems, and it’s too bad that Trump killed a bipartisan bill that would have closed asylum loopholes. But while America’s system of legal immigration could be improved, it is, on the whole, “good enough,” and if we simply made it larger, that would be a big win for the economy. If we improved the allocation of visas, that would be great. But it would only make the case for expansion of legal migration even stronger.

Bad policy begets bad policy

All that said, over the past five years, immigration restrictionists have finally come up with an argument that I think is factually accurate: The more immigrants we have, the more housing scarcity pinches.

You see the same problem in a domestic migration context, where people worry about gentrification and displacement. In principle, a company deciding to make a big investment in your town and hire lots of people at high wages should be great news for the local economy — the quintessential economic development success story. Realistically, though, the lowest-wage workers in your town aren’t going to be qualified for the new high-wage jobs. And if new high-wage jobs just cause new rich people to move to town and start bidding up the price of housing, that may even be bad for the incumbent group of low-wage workers who find themselves needing to accept longer commutes. This is why a state like California has seen net domestic outmigration over the past 20 years, even as the California-based technology industry thrives. An economic growth dynamic that should be win-win turns into a zero-sum scramble for a fixed pool of housing.

I mention the California case, though, because restrictionists have started invoking housing scarcity as a case against immigration when it’s really something more like a generalized case against growth and prosperity. I would rather get $1,000 than see you get $1,000. But in a healthy economy, you getting $1,000 isn’t bad for me. At worst, it’s neutral — you have money and I don’t. But your $1,000 should have some upside for me. Maybe I can sell you something. Maybe I can benefit from your contributions to the tax base.

Housing scarcity throws this off. Your $1,000 may just bid up my rent and leave me worse off.

Note that from a strict housing point of view, skilled immigration is worse than unskilled. An asylum-seeker is likely to end up in a shelter or on the streets, while a programmer earning a six-figure salary is competing in the rental market.

I mention all this because while it’s true that immigration exacerbates housing scarcity, I think the conclusion that we shouldn’t have immigration is pretty flawed. It’s as if a city were to deliberately keep crime high as an affordable housing strategy. All kinds of good policies can be transmogrified into “potentially harmful to low-income renters” via regulatory constraints on the supply of housing. But that just shows that regulatory constraints on the supply of housing are really bad!

And I think there’s a more general point here. There are lots of ways to enrich specific groups of people with supply-side restrictions. If you don’t let foreign computer programmers move here, that boosts earnings for native programmers. If you don’t let people build new houses, that boosts the wealth of incumbent homeowners. If you don’t train more doctors, that boosts earnings for doctors. If you ban port automation, that boosts earnings for longshoremen. But you can’t make the country as a whole richer with these piecemeal handouts for everyone — the more you try to add up supply constriction, the poorer everyone gets.

“ someone always raises the concern that this benefit to foreign-born wage earners generates downward pressure on native-born wage earners.

But H-1 workers’ earnings are well above the national average, so they can’t be pulling down average wages.”

What? Matt brought up a concern and then answered a different concern. If an H1B comes in at $150k to a job that would ordinarily pay $200k, and into a country in which the average wage is $100k, then he is creating downward pressure on wages but increasing the average wage IF the position would have gone unfilled without an H1B. Otherwise he is creating downward pressure on BOTH native-born and average wages.

"Housing scarcity throws this off. Your $1,000 may just bid up my rent and leave me worse off."

Tangentially-related, this is basically the second reason I sometimes feel so personally peeved about student loan forgiveness (the first being that it is poorly targeted). I paid off my loans at the expense of saving up for a down payment. When I did ultimately buy a house (which I waited to do until my 40s), I had a very tight budget and could only afford a fixer-upper -- which I now actually can't afford to fix up. Like, we literally have a shower we haven't been able to use for over a year because the toilet leaked on the floor, the floor had to be removed to fix it, and I can't afford the additional renovations needed to put everything back into working order. (And no, Dad, I'm not competent to do it myself, nor do I have the time to teach myself plumbing, tiling, electrical, and flooring as the parent of two young kids with a full-time job.)

Considering that I'm pretty much smackdab in the middle of the population cohort targeted for loan forgiveness (older Millennial), it was hard for me to escape the feeling that my peers getting significant loan forgiveness wouldn't actually put me at a disadvantage when it came to competition in the housing/renovation market. So when people asked, "Why does it bother you if others get help?", my answer was, "Because it hurts ME!"

I probably wouldn't mind loan forgiveness at all if I personally wasn't struggling so much with housing costs as a result of paying off my own loans. Alternatively, if I could get retroactively reimbursed for loans that would have been qualified for forgiveness today, that would also make me feel better.