Kyrsten Sinema must be stopped

The most dangerous possibility — she believes everything she says

Progressives should love and cherish Joe Manchin. If you look at West Virginia’s underlying partisanship, he is clearly the person with the highest Value Over Replacement in the whole Senate.

Beyond his stellar VOR, though, Manchin is clearly yesterday’s man. I can remember when Al Gore’s performance in West Virginia in 2000 was considered surprisingly weak in a traditionally Democratic state. Very recently, Dems held two Senate seats there despite the state’s sharp rightward tilt in national politics. Democrats are lucky Manchin got re-elected in 2018, and realistically, it would take a miracle for him to win again in 2024.

And then there’s Kyrsten Sinema.

Her home state is much less red than West Virginia. And her electoral performance is unimpressive compared to the partisan fundamentals. Beyond that, her objections to the Biden agenda — as far as we can tell — don’t really come from a standpoint of political prudence or electoral calculation at all. Instead, she largely seems to object to the most popular, most populist ideas that Biden has.

It’s extremely hard to forgive. And it’s also alarming. Because while I don’t believe Kyrsten Sinema will be the future of the Democratic Party, one can at least squint and sort of see it. So far, most of the newly elected Democrats from favored quarter suburbs are pretty solid liberals who still back taxing the rich and expanding the welfare state. But Sinema and a handful of her allies in the House do portend a possible alternate route where Democrats try to turn themselves into a pro-business identity politics movement that mostly just gets creamed by the populist right.

It’s a very alarming development, and unless she changes course quickly, it would be very advisable to mount a primary challenge to her.

Sinema’s electoral performance is nothing special

Arizona is a less conservative state than West Virginia, but I was impressed by Kyrsten Sinema’s 2018 victory. The state has a pretty conservative track record, Democrats hadn’t been doing well there recently despite high hopes, and honestly, you take any wins you can get when you’re running against the badly skewed Senate map.

That said, we wound up getting an unusually direct comparison because after Sinema beat Martha McSally, Arizona governor Doug Ducey turned around and appointed McSally to fill the vacancy in the state’s other Senate seat. So in November 2020, Mark Kelly also beat Martha McSally in an Arizona Senate race.

Sinema beats McSally 50-47.6 — a 2.4 percentage point margin —and Sinema gets 51.2% of the two-party vote.

Kelly beats McSally 51.2-48.8 — a 2.4 percentage point margin — and Kelly gets 51.2% of the two-party vote.

Those results are eerily identical. Normally in politics people can argue all day about comparative electoral performances, but Sinema and Kelly did the exact same, and they did it against the exact same opponent.

Now what you can say for Kelly is he’s an astronaut, which is awesome, and there aren’t that many astronauts out there you can recruit. But we also know that the overall national political climate for Democrats was considerably stronger in 2018 than it was in 2020. Quite a few House members managed to win Trump-leaning seats in 2018 only to lose them in 2020. And there’s good reason to believe that a bunch of Senate Democrats who won in 2018 (Jon Tester, Sherrod Brown, the aforementioned Manchin) would have lost in 2020’s climate.

I firmly believe that the evidence shows moderates do better at winning elections in general, so I really am trying to make a specific point about Sinema here. In general, moderate Democrats are not nearly as popularist as they should be. But Sinema takes this to some unusual extremes.

Sinema’s objections to the reconciliation bill are politically unsound

Sinema has been the key objector to Democrats’ prescription drug pricing proposal, which (as we saw from David Shor’s polling earlier this week) is literally the most popular item on the Democratic agenda.

She also said she’s opposed to any kind of increase of corporate or individual income tax rates, even floating the insanely unpopular idea of a carbon tax as an alternative.

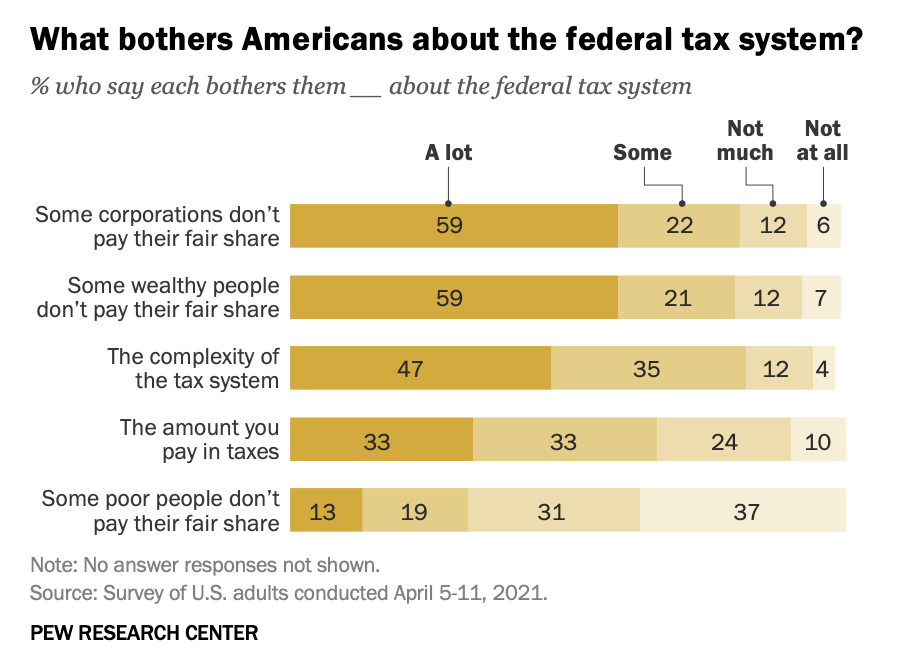

The idea that wealthy people and corporations pay too little taxes is Americans’ number one complaint about the current tax code.

Remember that strong national political environment Democrats enjoyed in 2018? A big reason it was so strong is that Trump and congressional Republicans pushed through a giant business tax cut that was hideously unpopular. Trump’s low point in the polls had nothing to do with Covid or Russia or scandals or inappropriate behavior — it was when his top political priority was revealed to be helping rich people and global businesses.

I don’t particularly want to be a white knight for this reconciliation package per se, as it includes a few half-baked ideas and in general seems to be to reflect a party-wide failure to set priorities. But the broad strokes of “partially roll back Trump’s tax cuts, reduce prescription drug prices, and use the money to fund some programs” is perfectly sound politics and policy whether or not you get all the way up to $3.5 trillion.

Sinema maybe loves regressive tax cuts

Speaking of TCJA, the GOP engaged in some trickery when putting it together. They paired a bunch of unpopular, regressive tax cuts with some popular tax cuts with benefits for the middle class. But to make the bill look cheaper, they scheduled those middle-class tax cuts to expire after a few years, making only the unpopular ones permanent.

Of course, once it was enacted, they immediately started pressing to make the other tax cuts permanent.

I don’t really approve of that, but I didn’t find it particularly surprising that Sinema, along with several other House members who were either in frontline seats or else running for higher office (hi, Jacky Rosen!), voted yes on permanence the first time this came up.

But there’s something very interesting about Sinema’s explanation as to why she voted yes.

My big complaint when the tax bill passed last November was that it didn't provide permanency for small businesses who use pass-through taxes to run their businesses and it didn't provide permanency for middle-class families, so I voted no.

The bill that Congress passed recently extended those two provisions, my chief concerns, which is why I voted yes.

Sinema could have — but did not — say she voted against the original bill because she opposed the huge regressive tax cuts that it made permanent, but she had no objections to the temporary provisions she was now extending. Instead, she said that the temporariness of the temporary provisions was her “big complaint” about the bill, raising no objection to the large, unpopular regressive tax cuts.

That’s consistent both with her current negotiating position on the reconciliation package and also her status as a bad popularist.

Is Sinema on the take?

The progressive master-narrative about anything they don’t like in Congress is that it’s the corrupting influence of big money.

So naturally, since Sinema has become a thorn in the side of the Biden agenda, we have seen a lot of articles about her hanging out with pharma lobbyists and speculation about her potential plans to crash and burn after one term in the Senate and hang out on K Street. And obviously, it’s true that Sinema’s emergence as the key veto player means that corporate lobbyists are swarming all over her.

That said, I think progressive thinking on money in politics is generally pretty outdated and tends to reverse cause and effect.

In recent cycles, Democratic candidates have had no problem raising money. Indeed, Democrats have had so much money that deep longshot campaigns like Jamie Harrison in South Caroline or Amy McGrath in Kentucky end up showered with cash. Studies show that large-dollar Democratic Party donors are generally to the left of rank-and-file Democratic Party voters and small-dollar donors are even further left. As we saw in the 2020 primary, small-dollar donors love Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Big money loved Pete Buttigieg and Beto O’Rourke. The voters loved Joe Biden.

In other words, if Sinema wanted to be a strong progressive ally, she would have plenty of cash for her reelection campaign. I don’t anticipate Mark Kelly will struggle to raise money, for example.

Sinema isn’t blocking popular progressive ideas because she’s getting corporate money; she’s getting corporate money because she’s blocking popular progressive ideas, and businesses want their key ally to succeed and prosper.

Sincerity — the most underrated force in politics

One big takeaway from the Trump years is that free-market economics is not a big motivating factor for rank-and-file Republican Party voters, who care much more about culture war topics. But if you know anyone involved in elite levels of conservative movement economic policy (which frankly and sadly, few progressives actually seem to), then it’s hard to escape the conclusion that there is a very painful sincerity behind the belief that low taxes on rich people are the right strategy for humanity.

The debates about this are complicated, obviously, but the idea is that low taxes facilitate economic growth. And because economic growth compounds over time, even a tiny amount of growth is an incredibly big deal over the long term. A year of 2.2% GDP growth vs. 2.3% GDP growth doesn’t sound important and certainly isn’t politically transformative. But over a hundred years, that 0.1 percentage point boost can be a lot. Yet in electoral politics, the siren song of redistribution — which makes short-sighted voters happy in the short-term — is always powerful, and the real heroes of politics are those who (by any means necessary) keep taxes as low as possible.

A similar argument is that pharmaceutical price controls naturally appeal to voters’ lizard brains but that even slightly slowing the pace of pharma innovation isn’t worth the price.

Lots of the people who think this way (possibly even most of them) disapprove of Trump’s antics, aren’t necessarily on board with the full conservative cultural agenda, and find the populist tilt in Republican rhetoric somewhat alarming and disorienting. Some of them really like Kyrsten Sinema and Josh Gottheimer and hope to find a future beachhead for pro-business politics in the Democratic Party. And I think it’s at least plausible that’s exactly what Sinema what like to do.

Thanks to education polarization, Democrats are increasingly becoming the party of college graduates. That has so far not led them to abandon populist economics — Joe Biden is trying to implement a very ambitious expansion of the American welfare state.

But you can imagine a world where Sinema-ism takes over, and Democrats become an upscale suburban party that supports free trade and balanced budgets. A party that doesn’t rock the boat and taxes and spending. Where everybody reads “Lean In” and “White Fragility” and makes sure the company they work at runs DEI seminars. And, where you are constantly losing elections due to the lopsided nature of the Senate map, but even when you do govern, you’re just a kind of technocratic clean-up crew that doesn’t really try to tackle major social problems. I think you got a flash of what that kind of politics might look like in the final couple years of Bill Clinton’s administration, but then in the 21st century, Democrats broke left on economics rather than right.

But nothing is inevitable in life, and I think there is a plausible world in which Sinema is the future. And to people who actually care about addressing things like America’s sky-high child poverty rate, the tragic persistence of medical bankruptcies, and the inadequacy of our provisions for young children and their parents, that’s a real problem.

Bigger than BIF

I am the furthest thing in the world from a DINO hunter, but I really do think that if Sinema persists in this course, it would be worth mounting a strong primary challenge to her.

Realistically, the 2024 Arizona Senate race is going to be tough for Democrats, and intra-party fighting makes it tougher. But she’s not some massive electoral overperformer (if anything she may be below average) because her distinctive stances are less popular than normal Democratic Party stuff.

I don’t think it’s a huge secret that Rep. Ruben Gallego from Phoenix took a hard look at the 2020 Senate race. And in most respects, he’d be a great recruit for that kind of thing — young, combat veteran, Harvard grad, Hispanic — but in 2020, he would’ve been up against an astronaut who came out of the gate with solid polling, national party support, and a big email list inherited from his wife.

Could he run in 2024? I don’t see why not. In 2016, he ran 0.73 percentage points behind Clinton in his district, while in 2020 he ran 1.6 points ahead of Joe Biden (reflecting Biden’s relative weakness with Hispanics). I genuinely wouldn’t suggest something as potentially destructive as a primary challenge to an incumbent senator just over her unwillingness to break the filibuster or her enthusiastic objection to a $15/hour minimum wage. But she seems willing to tank the entire Biden legislative agenda over a very profound point of disagreement — no tax increases.

That’s a definitional question for a Democratic Party that, frankly, ought to be open to more of a big tent approach on guns, abortions, and other cultural issues but which definitely needs to retain its anchor as the party of taxing the rich and redistributing the wealth. The idea that you can leverage or punish Sinema by spiking the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill seems nuts to me. For starters, it’s a pretty good bill! But beyond that, if the left spikes it, she’ll live; that would just be spite. What we’re dealing with here is bigger than that and needs a bigger solution.

Seems like Sinema is trying to emulate McCain’s maverick persona, e.g. his thumbs down on ACA repeal. But the thing is, McCain almost certainly would have lost his next primary. Also… there is a difference between voting down unpopular bills and standing in the way of popular bills.

Anyway, I think it’ll be important for the “primary Sinema” movement to frequently contrast Sinema and Kelly (“while Mark Kelly is fighting to lower prescription drug prices, Kyrsten Sinema wants to keep prices high to protect her donors”). Bolsters Kelly’s popularity while also making the objections to Sinema seem more reasonable, not just far-left complaining.

Two Sinema episodes from her House career standout, and I think demonstrate that she may very well be sincere, but politically stupid.

Back in 2013, as a freshman member, Sinema voted for the original GOP Farm Bill which famously failed on the floor (https://www.politico.com/story/2013/06/how-the-farm-bill-failed-093209) because a significant share of Republican members felt like the bill didn't cut spending enough, while the cuts to food stamps had alienated the Democratic caucus.

But 24 Democrats did vote for the bill, and they are largely the moderate to rural Democrats from farm-oriented districts. And then there was Sinema, from a suburban Phoenix House seat, voting for cuts to food stamps for ... reasons? To be politically moderate?

It didn't really make sense, and the reports at the time were that she cried on the floor, overwhelmed by the vote to cut food stamps while reflecting on her own time growing up as a child homeless and dependent on government assistance. She sincerely felt like she had to vote yes, even though it was "difficult" for her.

Less compelling, but still interesting, a few years later, Sinema is one of the only Democrats to back a weird proposal from House Republicans to privatize the air traffic control system (https://thehill.com/policy/transportation/341367-crunch-time-for-air-traffic-control-push). It's a bit wonky, and the idea itself (Canada has a similar approach) isn't necessarily bad, but the GOP version was tilted heavily towards the big airlines and their demands. But Sinema hadn't been seen as a big aviation policy person and wasn't on the Transportation Committee. It was widely seen as "Oh there's Sinema doing whatever the corporations want."

One of the only other Democrats to back the idea at the time? Josh Gottheimer.

Her political instincts seem heavily influences by corporate lobbyists and their view of the world. That's been clear recently with the reconciliation fight, but it's been apparent for some time from her House career. Just no one cared when she was just one House member.