I was talking recently to a smart Democratic Party elected official who told me that while Democrats generally prefer to talk about specific issues rather than broad values, most voters care more about values most of the time, and Democrats need to learn to talk about their values to connect with people.

I hear a version of this quite frequently, and I do think the advice contains a half-truth.

Most people do care a lot about values, and there is something quite limiting about presenting yourself as a disembodied policy laundry list. The problem is that while Americans are “operationally liberal” on many (though by no means all) issues, most Americans do not affiliate with the abstract values of the left.

That doesn’t mean the point about values is wrong. But it does mean that talking about the values espoused by college-educated congressional staffers and college-educated journalists and college-educated progressive advocacy organization staffers is probably counterproductive. To connect with the voters this official is talking about, you need to talk about different, more conservative-sounding values.

“One Billion Americans” was not, sadly, met with universal praise and acclaim. But it was interesting to contrast the mixed reviews from different outlets. A common reaction on the right was something like, “Yglesias didn’t convince me of all his ideas but some of them sound pretty good and it was refreshing to see a liberal talk about patriotic themes and how children are good.” A similarly mixed review from the left tended to go in the opposite direction: “most of these ideas seem fine, but it’s terrifying and fascistic to be talking about competitive great power politics and national greatness.” I think that means that if the book were a political candidate, it would be pretty well-positioned to run in a purple or reddish state — but it would also be moderately challenging for OBA to win a primary. A laundry list of proposals — child allowance, daycare allowance, universal preschool, immigration reform, zoning reform, transportation investments — without much talk of ideology or values probably would have been more comfortable.

Of course, I didn’t write that book and I think Democrats’ intuition that the laundry-list style of politics is limiting is correct. But if you want to play the values game, you need to go in with open eyes.

Americans’ values can be pretty bad

In August of 2014, Dara Lind did a write-up for Vox of a study indicating that people primed with information about racial disparities in the criminal justice system become less supportive of reform.

If you spend a lot of time marinating in the progressive value system, that sounds insane. In progressive spaces, the idea that something creates or exacerbates racial gaps is held — at least on the level of rhetoric — to be a kind of policy trump card. Reasonable people can disagree as to whether progressives genuinely prioritize antiracism or the centering of the experiences of the most marginalized people (and I think the answer is probably no), but the rhetoric matters, too, because it expresses a set of commonly shared values.

And the point of Dara’s piece was that those are not most Americans’ values. Most people see benefits to harsh law enforcement tactics, but also costs, and if you tell them the costs will be borne by members of an ethnic group that they, their friends, and their family don’t belong to, that shifts them in the direction of harshness.

Years later, a similar study came out about Covid-19. It turns out that drawing public attention to the racial gap in Covid mortality early in the pandemic made white people less supportive of mitigation efforts. Again, most people simply do not endorse the view that closing racial gaps is a high priority. They see tradeoffs with Covid NPIs, and telling them that the benefits of costly measures will mostly accrue to Black people makes them not want to take those measures.

Both of these examples pit white group self-interest against progressive anti-racism. But it’s important to remember that the group-identification point is true for most members of all groups. Democrats got, I think, a little lost in the fog on the politics of immigration at some point and conflated concern about the fate of long-settled illegal immigrants from Mexico (a topic that involves the friends and family members of many Mexican American U.S. citizens) with the issues of newly arrived asylum-seekers from Central America, South America, Haiti, and outside the western hemisphere. But just as diaspora Jews can be strongly pro-Israel without abstractly endorsing ethno-nationalist politics, Mexican Americans can be worried about mixed-status families and the impact of ICE interior enforcement on Mexican American neighborhoods without abstractly endorsing cosmopolitan values.

The spanking gap

Amongst college-educated parents in D.C., there is a strong norm against delivering physical punishment for misbehavior. You are instead supposed to control your child with Bene Gesserit Voice tactics, Jedi mind tricks, and the threat of lost screen time as a consequence of defiance. Working-class parents are much more likely to observe more old-school norms like “spare the rod, spoil the child.” In this case, I fully endorse the values and norms of my demographic groups and could, if challenged on this, point to things like the 2016 meta-analysis from Elizabeth Gershoff and Andrew Grogan-Kaylor concluding that spanking is bad.

At the same time, I do want to concede two points about this:

Being born to high-SES parents conveys a lot of social, material, and genetic advantages in life, so any high-SES parenting habits are going to strongly correlate with good life outcomes for kids.

Even though I’m broadly familiar with the results of the anti-spanking literature, my personal values were anti-spanking before I read any studies, and I haven’t actually done a deep dive into this research in part because even if you did convince me that the Gershoff/Grogan-Kaylor paper was wrong, we wouldn’t start spanking our kid.

The point is that in my social circle, this is a very strong norm. I’m quite confident that if you surveyed all the parents who work for Democratic Party members of Congress, who hold political appointments in the Biden administration, and who work for the DNC, DCCC, DSCC, and party-aligned super PACs, the vast majority of them don’t spank their kids. What’s more, those who do physically discipline their children would probably not talk about this with social and professional peers in D.C. because they know they’d face condemnation.

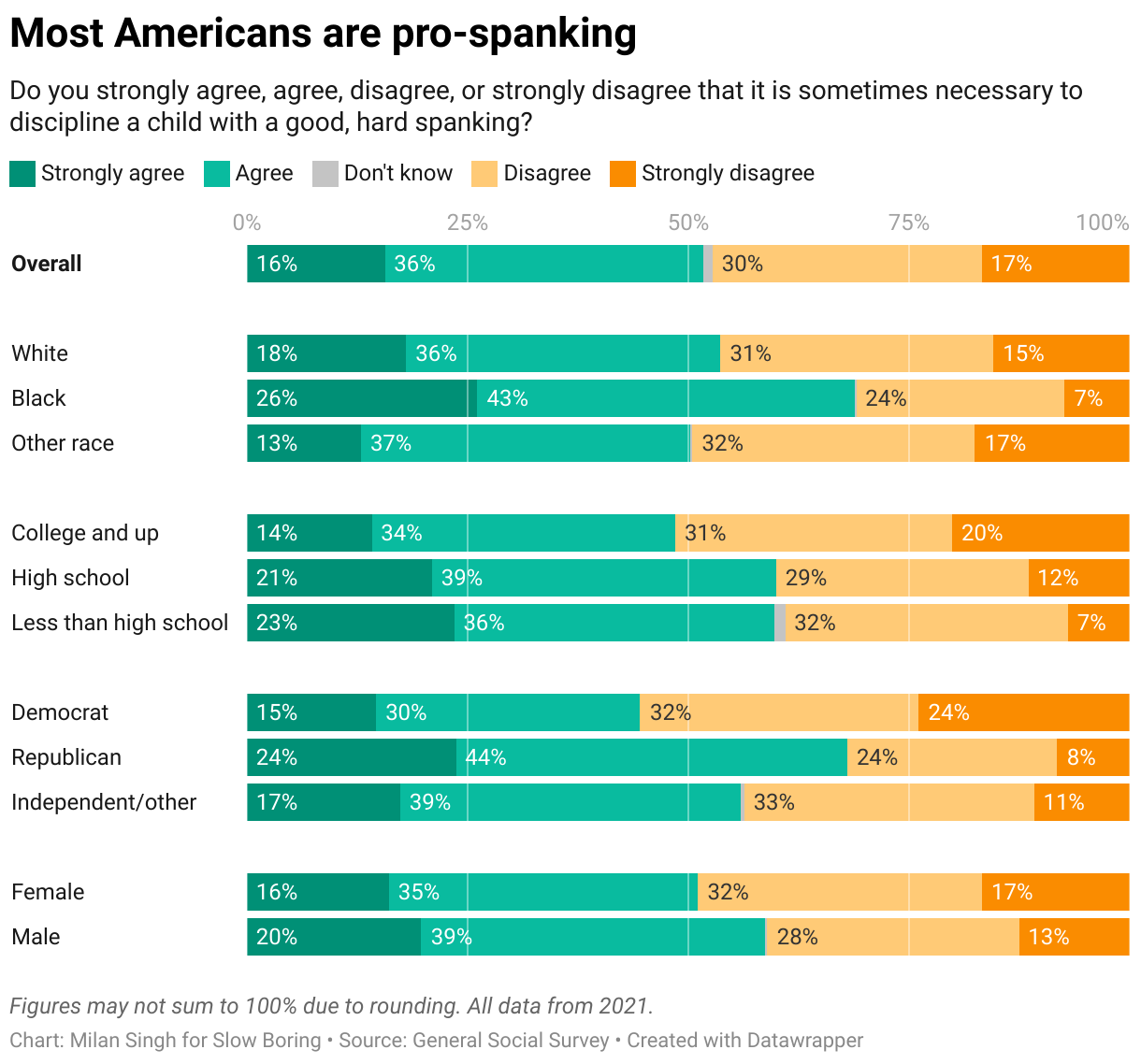

But in America as a whole, these values are held by a minority of the population with those who strongly disapprove of spanking (i.e., me and almost everyone I know) being a particularly small minority.

This is particularly important because, as Marc J. Hetherington, Jonathan Weiler, and Amy Erica Smith have written, attitudes toward child-rearing correlate strongly with a tendency to vote for candidates like Trump, Bolsonaro, or LePen.

But while I really liked their article, I think paragraphs like this tend to contribute to liberal complacency about their standing with non-white voters because as you can see in the chart, hard-ass parenting norms are typical of non-college people of all races:

The worldview of those who value traditional qualities in children is that the world is dangerous. It is best to keep children, and by extension society, on the straight and narrow. To them, the rapid political and cultural changes occurring around them — including increasing demographic diversity and sexual expression — pose a threat. They yearn for a simpler time, perhaps an imagined past, when life seemed more secure.

This is not to say that working-class African Americans are about to start voting en masse for Republicans because they think it’s appropriate to spank children. But this is an example where Democratic elites talking more “about our values” is mostly going to alienate voters they need.

In practice, I think you often want to do the reverse — signal affiliation with at least some of the other side’s values, even while you hold the line on policy.

The case of the Child Tax Credit

One particularly clear case of the contrast between talking about values (good idea) and talking about our values (bad idea) was the debate over the expanded Child Tax Credit. As you may recall, the expanded CTC reduced child poverty by a lot, but critics felt it was “welfare” and that it was bad to deliver cash benefits to people who were potentially not working.

I think the right way to answer this question, politically, is to cling for dear life to Mitt Romney and talk about how a good child allowance penalty can advance conservative values:

It helps working moms in much the same way that subsidized child care would, but it does so without loading the dice against traditionalist families.

Empirical research on prior tax credit expansions suggests it will lead to kids doing better in school and being less likely to join gangs.

Research on foreign programs suggests it would have a modest but real impact in terms of increasing American fertility rates, in part through the mechanism of fewer abortions.

If you are smart about it, you can roll CTC expansion together with initiatives to reduce marriage penalties in the welfare state.

The program is relatively expensive precisely because it is designed to not phase out when you accrue income, making it a much more pro-work benefit structure than is typical of the American welfare state.

Last but by no means least, I recommend strongly reassuring people that we do not see evidence that policies of this sort reduce labor force participation. A person receiving CTC checks is motivated to work for the exact same reason that people with part-time jobs seek full-time ones, or that people with minimum wage jobs try to find better-paying ones: the overwhelming majority of people are not satisfied with subsistence living and are willing to put in the effort to secure more money, even if they already have a non-zero amount of money. This is not a program that “pays you not to work;” it’s like a social security benefit for all children and parents that acknowledges that the market does not magically allocate additional income just because you have an extra mouth to feed, while fully preserving the incentive to put in an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay.

If somebody wanted to get deep into it on “why not do a work requirement anyway?” I might be willing to settle for half a loaf. But I’d really try to persuade them that the extra amount of work induced by a work requirement is essentially zero, while lots of hard-working families would inevitably end up accidentally excluded by administrative burdens. Say yes to families, say no to bureaucracy!

All of that is talking about values — but it’s not talking about leftist values.

If “talking about our values” means challenging the premise about the dignity of work, refusing to talk about gang involvement or marriage penalties because that pathologizes poor communities, neglecting fertility effects because it stigmatizes abortion, and instead repeating the phrase “fully automated luxury gay space communism,” then that is probably a mistake.

As Build Back Better morphed into the Inflation Reduction Act, I heard that participants in some coalition calls didn’t like the idea of emphasizing deficit reduction in a reconciliation package. They felt that it reinforced a bad narrative about politics and austerity. Ultimately, though, basically everyone did the right thing and switched from Green New Deal to Green Austerity. And I think that’s basically how politics works.

Tory men and Whig measures

On some level, this is all a longwinded way of saying that when it comes to ideology, self-identified conservatives outnumber self-identified liberals by a hefty margin.

Or that if you ask people about socialism vs. capitalism, capitalism wins.

Left-wing people rightly retort that this kind of polling conveys limited information about policy. And that’s right. But I think it conveys very important information about how left-wing people should conduct themselves. For example, the economist Roger Farmer has a book that I found convincing in which he argues that the Fed should buy stock during economic downturns to stabilize the economy instead of relying purely on the bond market. If you put that idea out there in practical politics, someone is going to say “no, that’s socialism!” And if you want to gain clout on Twitter, you might say “yes, socialism is good!” But if you actually want to see the idea adopted, you’re going to want to absolutely deny that it has anything to do with socialism — it’s just a pragmatic way to stabilize the economy. And you’re probably going to want to find some businessmen to endorse it.

When I wrote about Switzerland, I noticed that the Swiss have taken on a lot of the main features of a classic European welfare state without ever electing a social democratic majority in parliament. All of the policy change has involved partial co-optation of left-wing ideas by right-of-center figures. I think this is fundamentally how people like their politics.

There’s an old joke from Disraeli that a “sound conservative government” should consist of “Tory men and Whig measures.” That can take the form of Trump signing the CARES Act or doing a modest criminal justice reform bill. But it can also take the form of the proponents of Whig measures simply shading their self-presentation to seem more like they are Tories on the level of values. If you want to convince people that the American prison system is too harsh or that factory farming is cruel and in urgent need of reform, you probably want some of the spokespeople for that cause to believe in the efficacy of spanking. Because many people who are potentially persuadable about your idea are going to be fundamentally suspicious of progressive values. They want to be sure that you sincerely believe the evidence suggests your new approach will work, and not just that you’re some fanatic who doesn’t believe in hitting children.

This is hard to do

I’m lingering on this spanking theme because whenever this idea comes up, people’s go-to idea for a conservative value for liberals to embrace harder is patriotism. A lot of people think it would do a lot of good for Democrats to fulsomely embrace the kind of up-with-America attitude advocated in Richard Rorty’s “Achieving Our Country.” And I broadly agree with that (hence “One Billion Americans”), but the reason this comes up so frequently I think is precisely because it’s so easy. Barack Obama and Joe Biden are both big into rah-rah-Americana. And while I absolutely think that helps them politically relative to the alternative approaches, there are real limits to what can be achieved here.1

The spanking thing is tough because it’s way harder to fake it til you make it on that one.

A key variable in the Hetherington, Weiler, and Smith paper is whether you think it’s more important for kids to “respect their elders” or “to be independent.” And I’d genuinely find it kind of weird and alienating if Biden were to start doing a cranky old guy routine about how the problem with kids these days is that they don’t respect their elders enough.

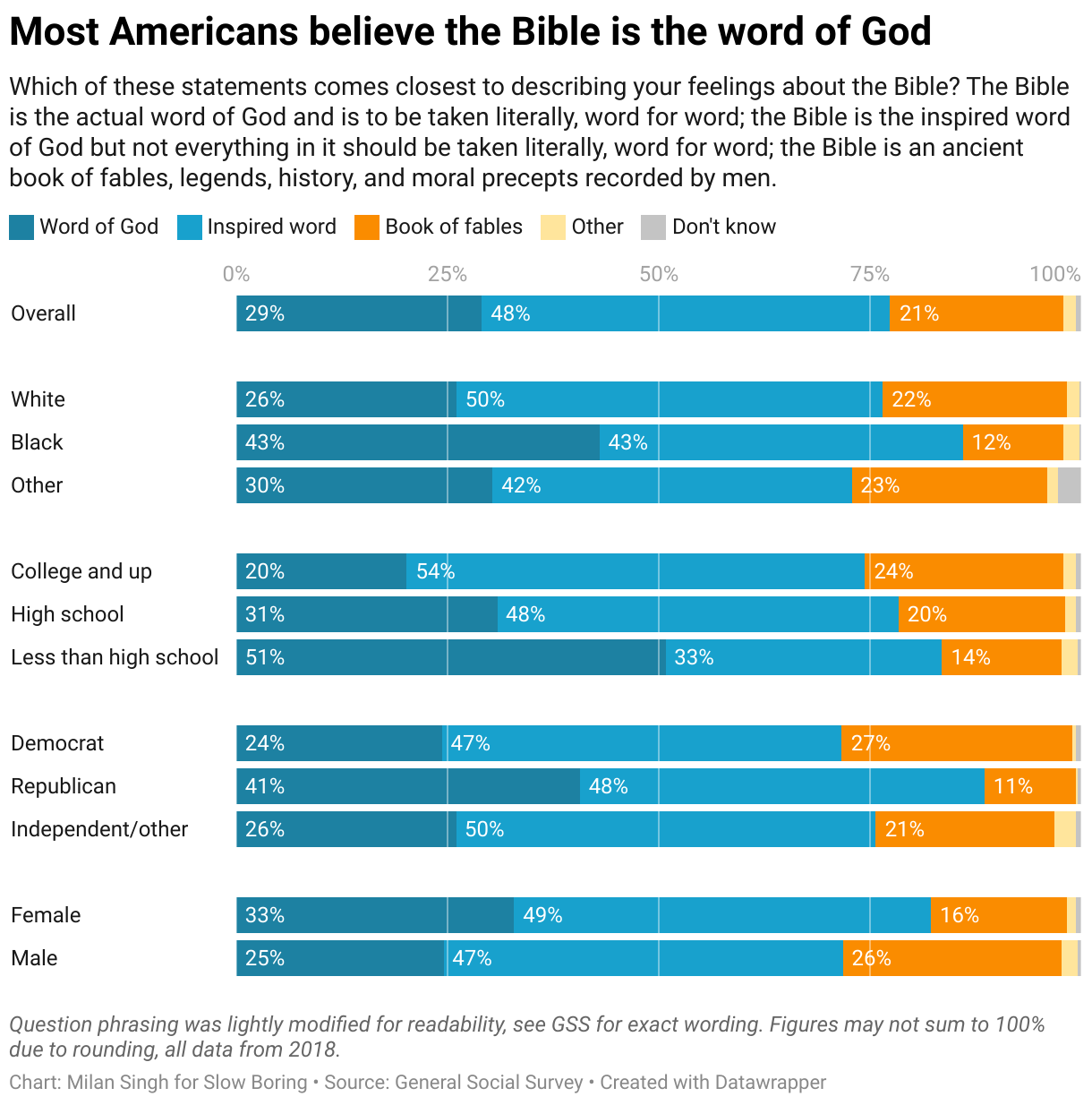

Or take this one about the epistemic status of the Bible. Atheism is just massively overrepresented among intellectual types and the kind of people who run things relative to the mass public. And of course on some level that’s why there are suspiciously few “out” atheists among Democratic Party elected officials. At the same time, you don’t see many candidates distancing themselves from “the Bible is fiction” the way they do from anti-patriotism.

But maybe someone should try.

The point, though, is that the values thing is a tough one. It’s absolutely true that values matters as much as, if not more than, issues to many people. But at the end of the day, the values of secular cosmopolitan liberals are much more marginal than many people realize, and talking about those values could be extremely dangerous. If you’re Raphael Warnock, a literal preacher, you probably should talk more about your personal relationship with Jesus Christ and how that influences your thinking about your job. But if that’s not your background, what you need to do is give your personal values a thorough audit and try to find some that you can articulate with conviction that also connect to the much more widely-held conservative worldview. Otherwise, a values debate is an entry into a potential world of pain.

This hits on an underlying theme of much of Matt’s writing: there’s something fundamentally unlikable about many American leftists. Figure out how to be more relatable/likable/normal and win more elections.

Its worth trying to empathize with the spankers. Physical discipline is probably more effective in the short term. I tell my eight year old to control his voice multiple times a day. Usually, he deflects, sometimes he even makes fun of me by repeating what I say in an hysterical falsetto. I bet he wouldn’t do that if I popped him a few times! I might also extract more domestic labor from him if I used a broader spectrum of coercion.

I stick to the mildest forms of coercion because my child can “fail” safety. But if my respectability were hanging by a thread and I were afraid of social services being called if we didn’t hold the line, or I needed Charlie to do the laundry because I were working two jobs, or even if I spent much of my weekends doing chores because we couldn’t afford help, I might give more weight to the short term efficacy of spanking and worry less about modeling non-violence.