Republicans can't even explain what they're trying to do with the debt ceiling

They want to cut ... something

One of the oddest elements of this year’s iteration of the debt ceiling drama is that even the people instigating it don’t seem to have much interest in the subject of the national debt or deficit reduction.

It’s of course always been the case that Republicans don’t want to address their concerns about the deficit with higher taxes. But this time around, the very GOP budget-cutters who are bringing the country to the point of crisis don’t seem to want to cut spending either. Donald Trump made a splash recently by coming out against changes to Social Security and Medicare and immediately got a thumbs up from newly elected Ohio Senator J.D. Vance.

Nancy Mace, a slightly moderate House Republican from South Carolina was asked on Meet The Press what she wants to cut and (a) couldn’t name anything to cut and (b) specifically ruled out Social Security and Medicare cuts. Her idea is that Congress should mandate some kind of non-specific overall reductions in discretionary spending and then leave it up to the agency heads to decide what to do.

Joe Manchin tried to defuse the crisis by proposing another run at the bipartisan commission exercise, only to see that rejected out of hand by the Freedom Caucus.

This is just to say that Republicans are trying to hold a negotiation about this, but they don’t actually have a negotiating position. Everyone has agreed amongst themselves that passing a clean debt limit would be a kind of cuck move and they don’t want to do it. But they don’t really know why they don’t want to do it other than that nobody wants to surrender, and I think they have a vague sense that “bad stuff happening” would be bad for Joe Biden. I think the belief that a debt ceiling crisis is damaging to the incumbent president is how Republicans got some leverage over Obama. But today — with a deeper public understanding of the issue, a clearer position from the White House on what they want, better elite comprehension of the available options, and a GOP whose stance on the issue is completely unclear — I don’t really think that leverage exists. We’re hurtling toward a very chaotic legal and constitutional situation for no real reason.

There is a process for cutting discretionary spending

The weird thing about the Mace/Vance/Trump position is that if they want to reduce appropriations for the discretionary budget, there’s an established process for that.

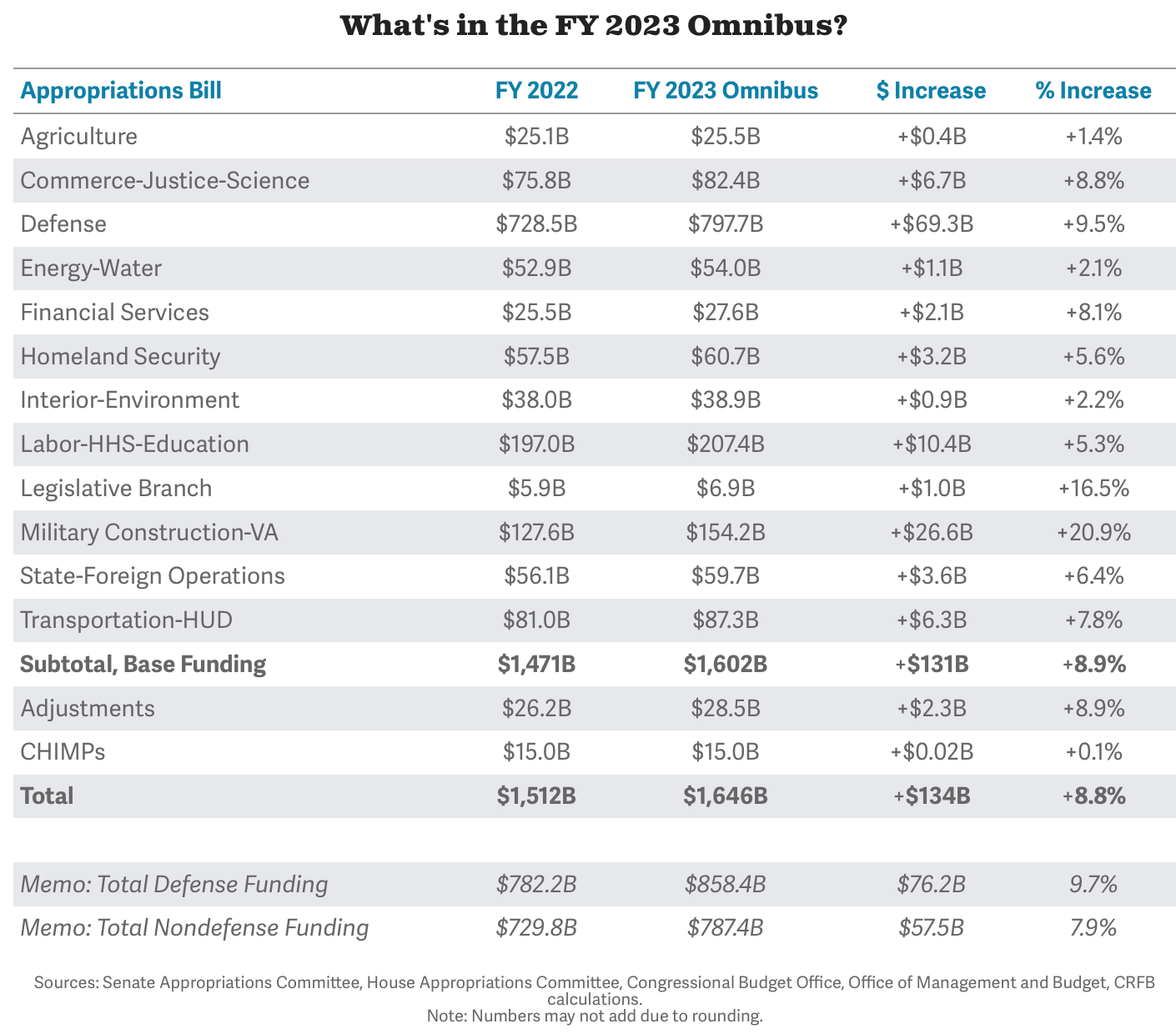

The fiscal year 2022 appropriations expired last year on October 1, and Congress passed what’s called a continuing resolution extending the old appropriations levels forward for three more months. Then at the very end of the year, a bipartisan majority reached an agreement on an omnibus appropriations bill for fiscal year 2023 and passed it. As you can see courtesy of this chart from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, this bill offered an unusually large increase in nominal spending. Some of that is inflation, but the pace of spending grew in inflation-adjusted terms — though with considerable variance across departments.

The key win that Republicans scored here is that the defense budget grew faster than non-defense appropriations. That’s important because defense/non-defense parity was a key concession Republicans made in the Budget Control Act of 2011, which they have now slipped out of.

On the other hand, the whole reason there was a Budget Control Act of 2011 was that back during that debt ceiling fight, Obama refused to cut Social Security and Medicare unless Republicans would raise taxes and Republicans refused to raise taxes, so they settled on a suite of discretionary spending cuts. A few years later, Republicans started feeling those cuts were squeezing the Pentagon too tight so they agreed to lift the budget caps in a way that maintained the parity principle. In the most recent omnibus, the GOP won an end to parity but did so by agreeing to an unusually large increase in appropriations.

But whatever you think about this whole series of events, we have a process in place for setting discretionary spending levels.

If Republicans want to write appropriations bills that set spending at a lower level and have the House pass them, nothing is stopping them from doing that. Democrats, presumably, would not agree to those cuts and there then might be a government shutdown and we’d see who the public sides with. Or Republicans could pass appropriations bills containing the cuts they prefer but also avoid a shutdown by agreeing to a continuing resolution. A CR that maintains current spending levels would be a cut in real terms, and the longer you’re able to hold out on the basis, the deeper the cut. The fact that Republicans didn’t cut discretionary spending when they held a trifecta in 2017-2018 is, I think, a little bit telling as to their level of commitment to this issue, but the point is there is a clear venue in which to fight about discretionary spending if that’s what they want to do. It even comes with a dramatic crisis moment in the form of a possible shutdown. There’s no need to do this debt ceiling bit.

Maybe they just really want to trash Medicaid?

Right after Trump won in 2016, then-Speaker Paul Ryan hoped to convince him to push for Medicare cuts.

Ryan failed in this, and a key fact in understanding recent American politics is that while Trump has many flaws, his most significant flaw for some conservatives like Ryan is that he’s too moderate in this respect. Trump and Ryan ultimately agreed instead to pursue savage cuts to Medicaid under the guise of Obamacare repeal. Since the Affordable Care Act put a lot of money into expanding Medicaid, repealing the ACA would of course generate a big cut to Medicaid eligibility. But that wasn’t good enough for Ryan and Trump, who added provisions that would cut Medicaid benefits down to less than the pre-Obama level.

The Speaker explained at the time that he’d been dreaming of Medicaid cuts ever since he was a college student.

One way to square the mathematical circle of wanting urgent action on the deficit without touching Medicare and Social Security would be to go back to the Medicaid cuts well.

Mace and Vance and others haven’t proposed that, and Kevin McCarthy certainly hasn’t worked with his committee chairs to generate a Medicaid cuts bill, but it’s possible that’s where this is going — cutting poor people off from their health insurance. That would represent a morally outrageous set of priorities, but it would at least give us a concrete explanation for why Republicans want to risk national bankruptcy.

The commission option is good

I already wrote this for Bloomberg, but I want to reiterate that Joe Manchin’s proposal to re-run the grand bargain commission idea from the Obama era actually makes sense this time around.

Republicans who need to face the voters don’t seem inclined to make any specific demands, so it’s hard to know what to negotiate over. Punting it to a commission might be simpler.

Much more so than during Obama’s day, the macroeconomic case for deficit reduction is actually quite strong.

Even if Republicans did come to their senses and agree to a bipartisan commission, the commission would deadlock unless Republicans agree to some tax increases.

Long-term fiscal talks have been deadlocked for 30 years because ever since George H.W. Bush lost in 1992, it’s been GOP dogma that his agreeing to a bipartisan deficit reduction bill that included higher taxes was the key reason for his defeat. Nobody seems to mind that Saint Reagan did the same.

So even though realistically, a bipartisan commission charged with formulating some balanced deficit reduction measures is a good idea, it seems politically futile. I’ve said before that I think it would be smart politics for Biden to seize the center ground by proposing a bunch of boring bipartisan commissions on various topics — including deficit reduction — and I still think that’s right. And even though I think a deficit commission would be doomed on substance, it does seem like a plausible route for a sane faction of House Republicans to jettison the Freedom Caucus and deal with the debt ceiling.

But failing that, I think it’s important for Biden to maintain the posture that there’s no genuine financial crisis here, and one way or another he will see to it that the bills get paid.

Debt management lessons from Chicago

The last time I wrote about high-coupon bonds as a debt ceiling option, I made some dumb errors that detracted from my main point.

But one generous reader was kind enough to send me Laurie Cohen’s May 18, 1992 article “Bigger McCormick Place Also Means Bigger Bonds” which ran in the Chicago Tribune on my 11th birthday and describes an interesting debt management situation.

The state entity charged with running Chicago’s convention center received authorization to borrow $937 million for an expansion project. But it turned out they needed $987 million. Because interest rates fell, they had the ability to service more than $937 million in debt — they were just stuck with an awkward statutory cap.

The controversial legislation authorizing new taxes for the expansion specified a $937 million cap on the bonds to finance it. But between the time the bill passed in July 1991 and the bonds were sold in December 1992, interest rates had declined substantially. The drop in rates meant that the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority, which runs the convention center, needed more money for the project because it would earn less interest on funds that were invested before being spent on construction.

The interest-rate decline also meant that the authority could issue more bonds without exceeding annual limits on debt service contained in the legislation. The only sticking point was the $937 million cap.

Rather than asking the legislature to boost the limit, McCormick Place and its bond dealers came up with a novel idea. As part of the huge sale, they included $30 million of bonds with a 50 percent interest rate.

Why would you sell bonds with a 50% interest rate? Well, because given the high interest rate, people were willing to pay $148 million for $30 million in bonds. And like magic, the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority was able to raise cash in excess of its statutory borrowing gap through the magic of high coupon bonds.

There are probably some implementation details that differentiate Treasury auctions from municipal bond sales, but the general point applies.

As long as the borrowing entity is able to make the interest payments, it doesn’t really matter whether you characterize something as $30 million in bonds with a high interest rate or $148 million in bonds with a low interest rate. And what the federal government is currently running up against is a statutory limit on the face value of bonds it is allowed to issue, not an economic limit on the amount of debt service it can manage. Republicans are in a state of internal chaos that seems to be preventing them from engaging constructively on the debt ceiling issue, so it’s imperative for the executive branch to begin laying plans to keep the country running. The Chicago Model seems promising.

Deep in their hearts, Republicans know that if voters are ever forced to chose between progressive tax increases or cutting old age entitlements, they will soak the rich. Insofar as Republicans have a rational position, they are flailing around to obfuscate that choice to neutralize a losing issue.

This is basically a search for silver bullets. Cuts to old age entitlements can never be hidden. Any Congressional majority that meaningfully cuts social security or medicare will be decimated in the next election.

In the short run, making this a fight over debt rather than spending makes sense, because spending is popular and debt sounds icky. In the long term, Republicans can’t possibly get what they want. The smart ones know this and have left the cult of low taxes.

Given how poorly McCarthy’s speaker election went, I cannot see how he rallies House Republicans around any spending cutting plan. He’s always going to be facing several attention-seeking maniacs who will vote against any potential bill while screeching to their supporters about how McCarthy is a sellout RINO who is compromising with Biden. In the unlikely event that these extremists actually propose cuts, they’ll certainly be too politically unpopular to garner support from moderate Republicans.

So I imagine we’ll keep walking to the abyss of a financial crisis, and eventually moderate Republicans will feel compelled to work with the Democrats to avoid the financial armageddon of a US Treasury default. McCarthy will either get on board with this bipartisan coalition or he’ll be replaced. Even the WSJ is considering this to be a likely scenario given the lack of any plan of what House Republicans actually want. [1]

> All of which means Republicans will have to pick their spending targets carefully, explain their goals in reasonable terms so they don’t look like they want a default, and then sell this to the public as a united team. The worst result would be for Republicans to talk tough for months, only to splinter in a rout at the end, and be forced to turn the House floor over to Democrats to raise the debt limit with nothing to show for it. Opportunists on the right would then cry “sellout,” even if they had insisted on demands that were unachievable.

> This is what Democrats expect to happen, which is why they don’t think they need to negotiate. If Republicans want to use the debt limit as leverage, they need a strategy for how this showdown ends, not merely how it begins.

[1] https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-hard-reality-of-a-debt-ceiling-showdown-house-republicans-congress-gop-11673904239