Remote work is boosting housing demand and driving inflation

Joe Biden has a plan to increase supply

Housing costs have escalated dramatically over the past couple of years. Part of the increase is the overall inflationary dynamic, but there’s also been a lot of attention paid to the prospect of remote work causing white-collar professionals to move to different metro areas or far-flung exurbs.

I’ve never been to Boise. But by all accounts, Idaho is a lovely and very scenic place that a lot of people enjoy visiting and maybe daydreaming about moving to. And now remote work has made it more practical for more people to actually do so.

But while those kinds of moves ought to change the relative price of housing (and indeed we do see that the Boise and Stockton metro areas have appreciated much faster than the San Francisco or New York ones), they don’t explain why the national housing market took off like a rocket ship starting in the summer of 2020.

Or do they?

In an interesting new paper, John Mondragon and Johannes Wieland argue that “the shift to remote work explains over one half of the 23.8 percent national house price increase over this period.”

A huge increase in housing demand

I live in a three-story rowhouse atop a basement apartment. That basement apartment used to be listed on Airbnb and generated rental income for my family. When the Covid-19 pandemic first struck — during the “slow the spread” era — we didn’t really host travelers. And then when it became clear that the office workers of the world were not, in fact, going to be called back in after two weeks, it turned out to be really useful to have some extra space free to use as a home office.

Of course, if I had a magic wand, I would configure the space differently so that the basement is structured as an office and a spare bedroom that are integrated into the main house rather than as a separate apartment. But moving is a hassle, so having a way to effectively make our home larger (by forgoing some rental income) without needing to move was very convenient.

This was a bit of an eccentric situation, but what Mondragon and Wieland argue is that it was on some level pretty typical — white-collar workers all across the country realized that they were going to be spending more time at home, and so they wanted to get larger dwellings.

Some of that could be families moving to larger houses. But I’ve seen a fair amount of evidence that we’ve lived through a surge in household formation — adult children no longer living with their parents, roommates splitting up to get a place of their own — which also fit into the same frame. When people spend more time at home they want more space, and when a large minority of the population all changes in the same way at once, it pushes up housing prices considerably.

I’m not going to pretend that I have the chops to check whether the Mondragon and Wieland math is entirely correct, but to test this they basically look at different metro areas’ levels of exposure to remote work (since job mix differs from place to place) and show that you get a higher increase in house prices where there is more exposure. The tricky thing is that you need to try to control for the fact that people also moved around — that’s the relative price issue that’s gotten so much attention — and that’s what they claim to have done here.

It’s all a bit tricky, of course, because one reason a person might move from California to Idaho or from Westchester to Saugerties is precisely that by moving somewhere where land is cheaper, you can get a bigger place. But conceptually these are distinct ideas. Even if you’re really rich and can afford a big house wherever you want, there’s still a question of where would you actually want to live. My family got a larger house without moving, and I have friends who stayed in D.C. while moving to a bigger place or who are currently looking at renovations to expand their existing home.

An awkwardly fast shock to our housing stock

The problem here is that if you’re a working-class renter, remote work hasn’t improved your life at all, but the surge in housing demand is raising your cost of living.

And the problem here is that remote work happened all at once. If you roll the clock back to February 2020, the situation in the United States of America is that remote work was growing at a steady pace from a low base. We also had lots and lots and lots of office buildings — some of them brand new, but some of them rather old — and the overall national population wasn’t growing very quickly. The “natural” economic dynamic would have been a prolonged transition period in which office demand was structurally weak. You’d have seen reduced levels of investment in building new offices, but that would have freed-up construction materials and labor to somewhat increase the pace of house-building. As suburban office parks aged to the point where their rental value was low, the tendency would have been to redevelop them as housing rather than to renovate or refurbish them.

Downtown central business districts wouldn’t necessarily have grown, but they wouldn’t have emptied out either. American cities tend to have a lot of job sprawl, and the natural tendency of the slow death of the office would have been to reduce that. The ratio of office square footage to people would shrink, but a higher share of the square footage would be concentrated in core areas.

The housing stock, meanwhile, could have just expanded. Of course, certain parts of the United States have been undersupplying housing for a long time. But remote work would have eroded the wage premium for being located in those metro areas and offered at least a partial solution to zoning and land use woes.

But instead, we got Covid-19 and a very sudden shift to remote work. That means we now have a ton of half-empty offices scattered in an undifferentiated way between central and peripheral areas, and we have a housing market that’s bursting at the seams because people don’t want to work remotely from a crowded kitchen table or a room that’s full of kids’ toys.

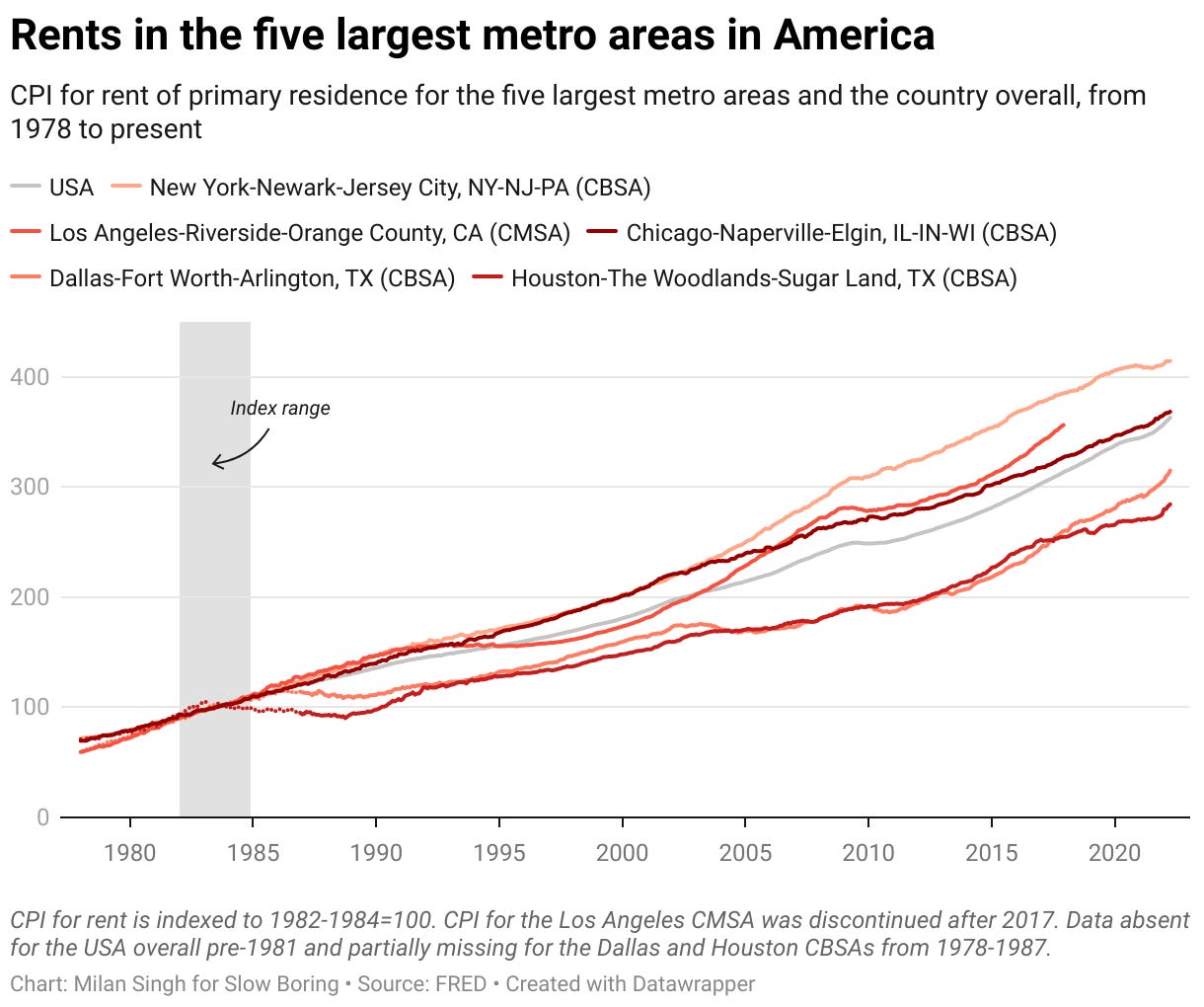

The result is that even as relative prices change a lot, the basic direction for everything is up — even in places like Chicago where increases have been relatively modest.

To an extent, this is just one of those things. Buildings are expensive and time-consuming to make and they also last a long time. Having a very sudden shift in what kinds of buildings people want (fewer offices and bigger houses) is a big pain economically because completely transforming the national building stock is hard.

But now we have to do the best we can.

Joe Biden’s plan to increase the housing supply

Last week, the Biden White House announced a series of housing policies starting with a core insight: “Today’s rising housing costs are years in the making. Fewer new homes were built in the decade following the Great Recession than in any decade since the 1960s — constraining housing supply and failing to keep pace with demand and household formation.”

That’s a big shift from the prevailing conventional wisdom during Barack Obama’s presidency when it was common to attribute economic problems to an alleged overbuilding of houses during the price boom of the mid-aughts.

Kevin Erdmann has been pointing out for years that a holistic look at housing supply — including apartments and trailers — shows there never was a real boom in housing supply.

Biden’s plan for action on housing has a few different moving parts, but it rightly focuses on addressing those underserved aspects of the market. They are pledging to use the discretionary grant programs under the Department of Transportation’s control (programs that are bigger than ever thanks to the bipartisan infrastructure law) to reward communities that change zoning to allow for more construction (Alon Levy and Emily Hamilton, as quoted by Tim Lee, both have some thoughts on implementation here). The administration also wants to change some of the Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac rules to allow for more financing of two-four unit “missing middle” projects, which could be important as interest rates rise.

It’s a little weird, though correct, to see DOT rather than the Department of Housing and Urban Development as the agency that’s really empowered to change land use. HUD does, however, regulate manufactured housing. This is important because as I’ve written before, the manufactured housing sector was deliberately kneecapped by regulators in the 1970s in order to protect the business interests of single-family homebuilders. The White House plan makes it easier for people to get financing for manufactured homes, but also mentions “updating the HUD Code to allow manufacturers to modernize and expand their production lines, and helping manufacturers respond to supply chain issues.” I’m not a lawyer and don’t really know how much discretion HUD has at their disposal, but I would urge them to go as far as possible in liberalizing here.

Because not only is manufactured housing an important option at the low end, but it seems like our best bet in the long run for actually increasing the productivity of the construction industry at a time when home completions are constrained by labor and building materials.

Protectionism is bad

The most dire housing economics trend, flagged by Joey Politano, is that even as builders are trying to build more houses, the pace at which they are actually finishing them has lagged due to a mix of high labor costs and expensive building materials. The White House plan does try to address the supply chain issues that have stymied this work, which is good to see.

I do, however, think this highlights the limits of addressing housing solely within a housing policy silo.

Biden’s housing plan doesn’t address the fact that his administration has largely continued Trump-era protectionist trade policies, some of which drive up the price of housing by levying taxes on construction inputs. But I would say more broadly that a lot of protectionist policy is motivated by the sense that allowing people to buy foreign manufactured goods causes mass unemployment among blue-collar men. The Great Recession really did involve prolonged mass unemployment, so I understand this line of thinking, to an extent.

But we are not currently experiencing mass unemployment, so every job “saved” by protectionism is simply reallocated from somewhere else. This is the classic, old-fashioned, textbook case for free trade — we can’t import apartment buildings from Korea, but we can import washers and dryers and have the people currently building appliances build apartments instead.

Immigration is the other major potential source of construction labor. The White House says they are working on unsnarling the visa-processing machine, which should be helpful here.

The broad story I would tell, though, is that the housing backlog is a great argument for good old-fashioned neoliberalism: housing is a regulatory issue, a trade issue, and an immigration issue all at once, and it’s by far the largest item in the typical household budget. Biden’s new policies are gesturing in the right direction, but there’s an extremely compelling case for going as strong as possible here. The country had a shortage of housing before the pandemic, and pandemic-era technological changes have sent housing demand through the roof — we should be doing everything possible to meet it.

I read through the White House document you referenced, admittedly expecting it to be infused with DEI language and written in a manner that was hostile to developers and landlords. IT WASN'T! It was balanced and measured and focused on the problem at hand. I'm impressed.

Though I still remember the eviction moratorium lasting far, far longer than it should have, I am encouraged the administration is approaching this issue with tangible solutions that could garner bi-partisan support. I hope they are successful.

Chicago has one difference from other cities. Their labor movement is stronger than their NIMBY movement. This has up and downsides. Downside is that property taxes are high AF to pay for public sector pensions. Upside is that stuff gets built because no local person mad about parking is going to have the political muscle to stop a housing construction project.

This is why when going through the loop, you see *residential construction* happening, and you've seen it for 5 years. Same in nearly every other area close to their urban core.

This combination makes home ownership less profitable due to the higher tax burden + no limit on inventory. It also makes politicians less prone to block housing, because housing drives local tax revenue in.IL in a way that it never will in CA with prop 13. Net result is condo rents have barely moved up since 2012 at the high end, maybe 10-20% or so over that span.

I lived there for 20 years, and the nice parts where the housing is being built are not dissimilar from the nice parts of Brooklyn. I'd still live there if the weather wasn't terrible for 5 winter months and 3 summer months.