Proportional representation is the solution to gerrymandering

Why not the best?

Democratic state legislators from Texas are on the run, trying to deny the GOP the quorum it needs to push through a mid-decade redistricting plan that would gerrymander the state’s maps more severely and net Republicans 3–5 seats. There are parallel pushes underway in Missouri and Indiana, and I believe there’s also a move to make the Florida map more Republican-friendly.

Some of this is just that even gerrymandered states normally aren’t totally maxed out for their majority party. But some of it (a theme that will recur in this article) is that the party coalitions are shifting somewhat due to racial depolarization, so in Texas and Florida in particular, there are chances for Republicans to re-optimize to fit their new and improved performance with Hispanic voters.

Democrats in several states are talking about retaliating with new maps of their own. There are, however, some procedural impediments to this.

California requires a ballot initiative to create new maps. Gerrymandering is unpopular enough that an initiative could quite plausibly fail even in a very blue state, but it’s also sufficiently low salience that state legislators who vote for skewed congressional maps are unlikely to face meaningful voter backlash. This asymmetry where Texas Republicans can do something mildly unpopular and expect the voters to blow it off while Gavin Newsom needs California residents to affirmatively agree to do something mildly unpopular is unfortunate. Because, on the merits, I think this is an extremely easy question.

Gerrymandering is bad. Democrats, to their credit, pushed for a national gerrymandering ban in 2021. Republicans, instead of crying crocodile tears about the (admittedly absurd-looking) congressional map in Illinois, should simply embrace the notion of a ban and get it done. But until that happens, nobody can afford to unilaterally disarm. If you live in California or some other blue state, you should push for aggressive maps.

Someday, I hope the system will change. The more interesting question, though, is how it should change.

And I hope that America will embrace the actually good solution to this problem — proportional representation — rather than expending efforts on gerrymandering fixes that aren’t as good or simply don’t work.

The shape of maps to come

One difficulty in getting cross-party agreement on solutions to gerrymandering is that Democrats and Republicans tend to have different concepts of what constitutes a gerrymander. Republicans tend to really focus in on the idea that gerrymandering means maps that look weird, with odd squiggles and strangely shaped districts. Democrats tend to focus more on the proportionality of a map. To Democrats, a quintessential unfair congressional map is something like Wisconsin, where the problem isn’t that the aesthetics of the lines are particularly egregious, it’s that Democrats won 48 percent of the vote in House elections but only got two out of eight seats.

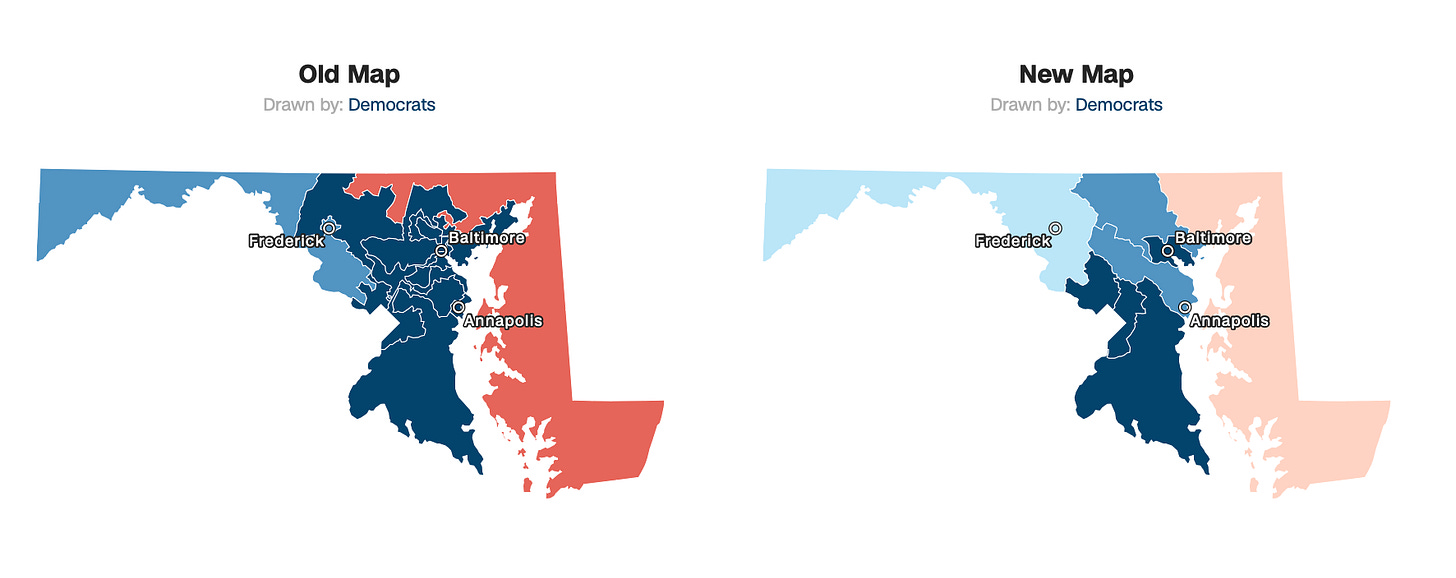

To illustrate the difference between these critiques, it’s useful to look at two different maps of Maryland that were both drawn by Democratic state legislators. The old map looked insane and used to be Republicans’ go-to example of an egregious Democratic gerrymander.

But the main motive for drawing such a weird-looking map was actually incumbent Democrats trying to manipulate the ethnic balance of their districts to avoid primaries. They were able to clean up the lines and greatly improve the aesthetics while retaining a 7-1 split. Of course, Republicans still don’t like that because in this case, it’s unfavorable to them either way. But they’ve mostly shifted their complaining to Illinois, which is now the signature funny-looking map.

The specifics of Maryland aside, the reason Republicans like to emphasize compactness and aesthetics is that in most states, maximally compact maps favor Republicans. It’s also normally the case (though again, not in Maryland) that an optimal Democratic map will involve drawing some narrow corridors through rural areas in order to connect scattered small college towns or majority-Black rural areas.

This is important because it means that even if both sides agreed to end gerrymandering, they wouldn’t be agreeing on what that means. Republicans would probably want to impose a strict compactness criterion in every state, which on average would mean the GOP secures more than 50 percent of the seats with less than half the vote. Democrats would want to impose a strict proportionality criterion in every state, which in many states would require maps that are odd-looking.

I don’t think I’m just being partisan when I say that Democrats have the better side of this argument.

Constituents aren’t traveling on horseback to have face-to-face meetings with their member of Congress, so what exactly are the virtues of compactness? When maps have massive partisan skew, that creates a concrete and specific problem for democracy. When maps are funny-looking, the problem is … I honestly don’t know what the problem is.

I will note, though, that conventional wisdom tends to be a bit of a laggard. The idea that compact maps would be super-beneficial to Republicans is, in part, an artifact of the Obama-era political alignment that resulted in incredibly high levels of racially polarized voting. The rising non-white share of the population combined with Republicans winning a larger minority of the non-white vote is reducing Democrats’ tendency to be packed into hyper-lopsided urban districts. At the same time, the GOP gaining an even bigger advantage with rural whites, but doing worse in suburbs, is creating more packed Republican precincts.

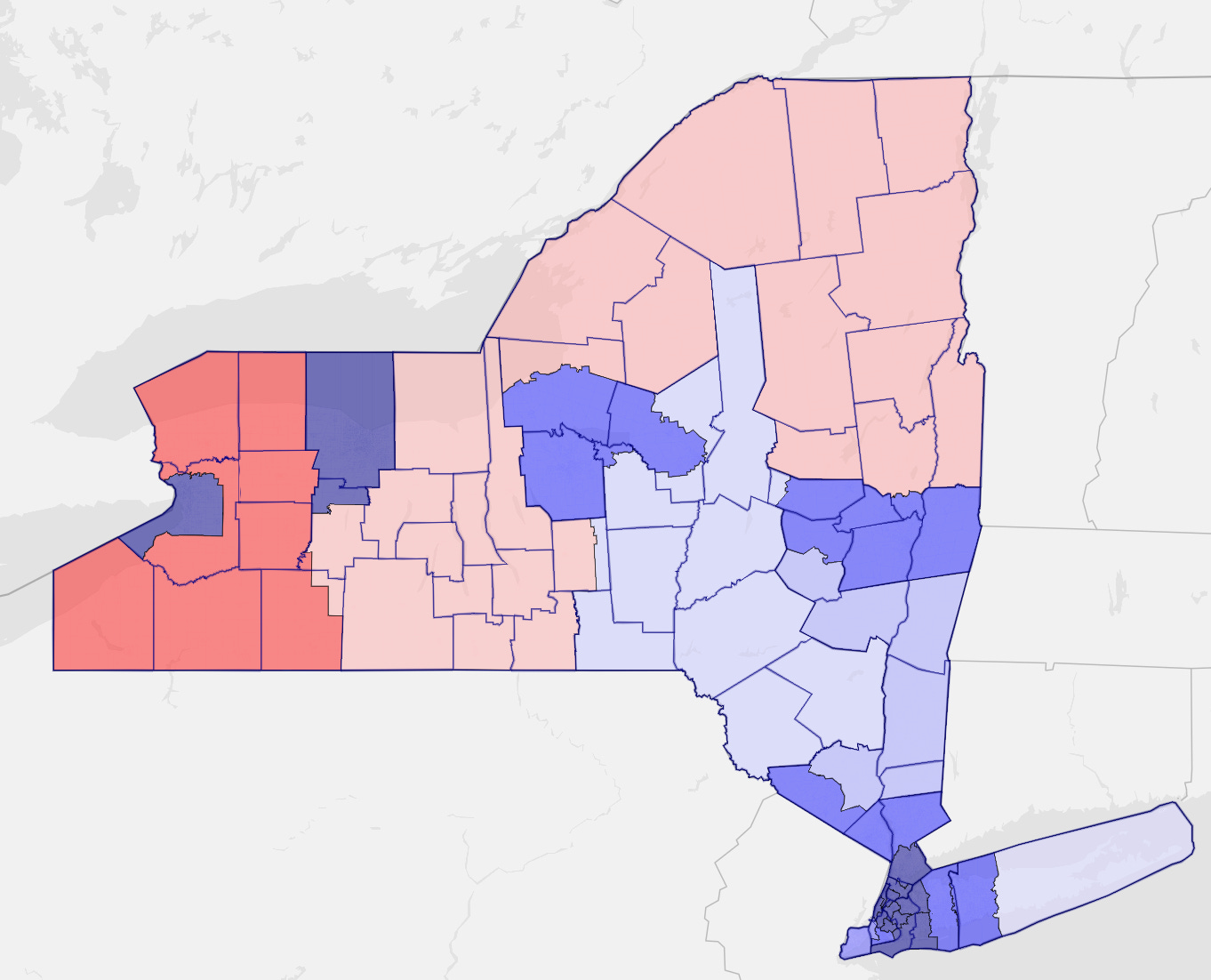

I drew this New York map while making no reference to demographic information, trying in good faith to respect county lines and be compact.

It ended up being an extremely aggressive 23–3 map for Democrats. The map that New York actually uses features two GOP seats on Long Island and one based on Staten Island. But straightforward vertical district lines eliminate those Long Island seats. Staten Island doesn’t have enough people to maintain its own congressional district. It ends up being a Republican-leaning district because they have chosen to link the island to some GOP-heavy parts of Brooklyn, but you could just as easily go in the other direction and make it a Democratic seat.

Gerrymandering could get more severe

One thing about my New York map is that not only is it more blue-skewed than the existing map without resorting to any particularly odd squiggles, it’s probably more aggressive than any map Democrats would actually draw for themselves. Not out of the goodness of their hearts, but because it contains seats that lean Democratic by margins like 0.7, 1.5, 3, and 4 points.

When real-world politicians gerrymander, they like to draw very safe seats for themselves and their colleagues. If New York completely scrapped its commission system and let politicians do whatever they wanted, I doubt they would draw a 23–3 map. I think they’re much more likely to produce a 21–5 map in which all 21 seats are extremely safe.

The parties don’t always gerrymander. Maine’s map is very friendly to Republicans and the New Hampshire map is friendly to Democrats. In Massachusetts, Democrats have a 9–0 map, but the population geography of Massachusetts is weird and only a bizarre shape would achieve an 8–1 map (and 7–2 is virtually impossible). But when they do gerrymander, both parties act as if their goal is to maximize the number of seats they can hold onto in a wave election that favors the other side.

This doesn’t make a ton of sense.

Winning more seats is always better than winning fewer. But it’s hard to think of situations in which the exact size of a post-wave House majority is the decisive factor in driving policy outcomes.

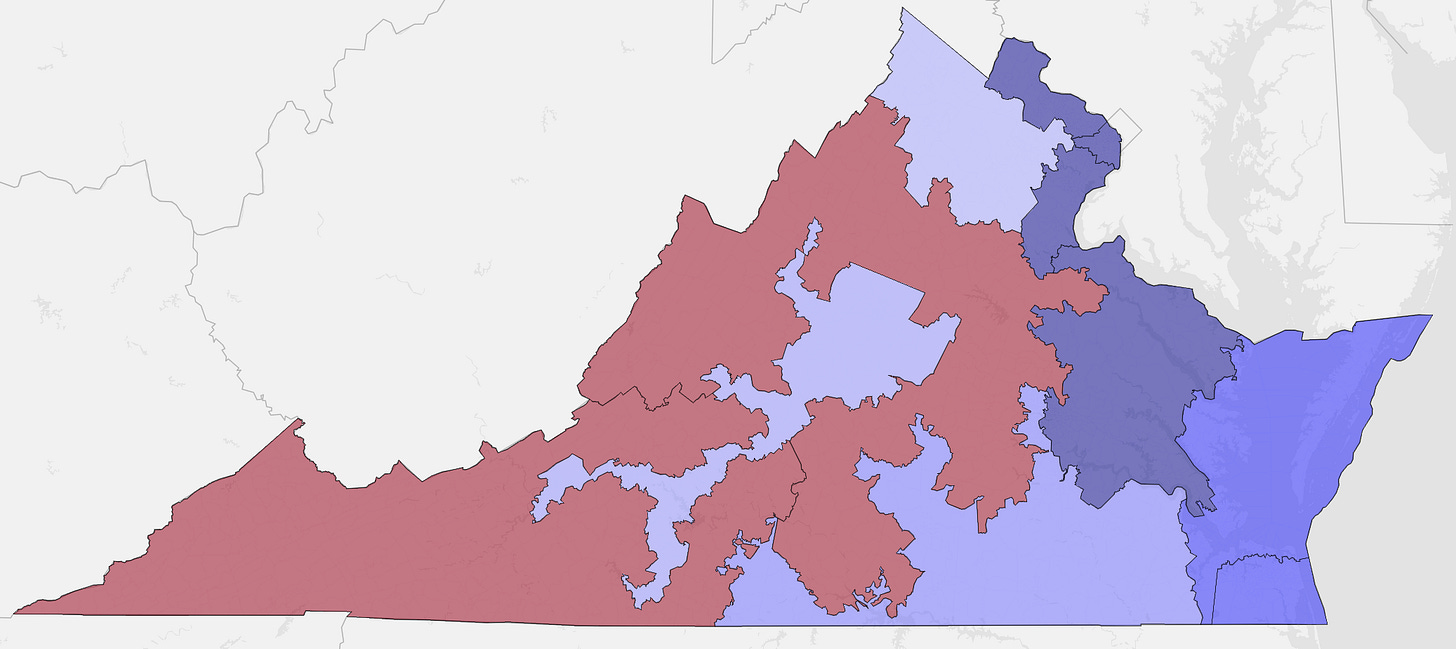

By contrast, it’s a huge deal that in 2012 the GOP won a small House minority on the back of a small loss in the popular vote. The consequences of a small majority versus a small minority are huge, especially in the House. So the rational thing to do from the perspective of a party hive mind is not to shore up incumbents in the face of a wave; it’s to maximize the number of seats that you win in a roughly neutral political environment. I drew this 7–2 map of Virginia, but the way you get to 7–2 is that three of those are blue-leaning rather than bright blue seats. Democrats would win them in a cycle like 2024, but lose them in a cycle like 2014.

Of course, the reason gerrymandering strategy is more conservative than in some sense it “should” be is that politicians are human beings, not partisan automatons. Life as an incumbent in a D+7 seat is much easier than life in a D+2 seat, so incumbent protection is prioritized above strategic party goals. But as the parties become more disciplined, I think we should expect that practice to wane in favor of increasingly aggressive gerrymanders. That’s over and above the procedural hardball of things like Texas redrawing between censuses. And we’re ultimately going to have to do something about it.

Why not the best?

Back during the Bush/Obama transition, I was at a conference with many of the top minds from the progressive legal world, who were briefing us non-specialists on issues in their domain. One of the subjects was gerrymandering, because (not knowing at the time how badly the 2010 midterms would go) there was a lot of interest in strategy around this for the upcoming census. The woman who presented on this emphasized that there are a lot of different goals that people want to pursue with their maps and that it’s not actually possible to pursue them all at once. Things like a desire to have competitive elections trade off against things like the desire to have partisan fairness. Both of those goals trade off against compactness.

Compactness trades off against ideas like “respect county boundaries,” because in many places the counties themselves are not compact. Trying to create majority-minority districts is another set of tradeoffs. Life is hard.

I asked her whether shifting to multi-member districts with proportional representation would make these tradeoffs easier. She said that when she teaches redistricting law classes, she comes to proportional representation last because it works too well as a solution, and the point of the exercise is to walk people through the tradeoffs. Similarly, she said she didn’t think it was worth discussing at a strategy conference because nobody is actually going to do it.

And I think that it is worth discussing for precisely that reason.

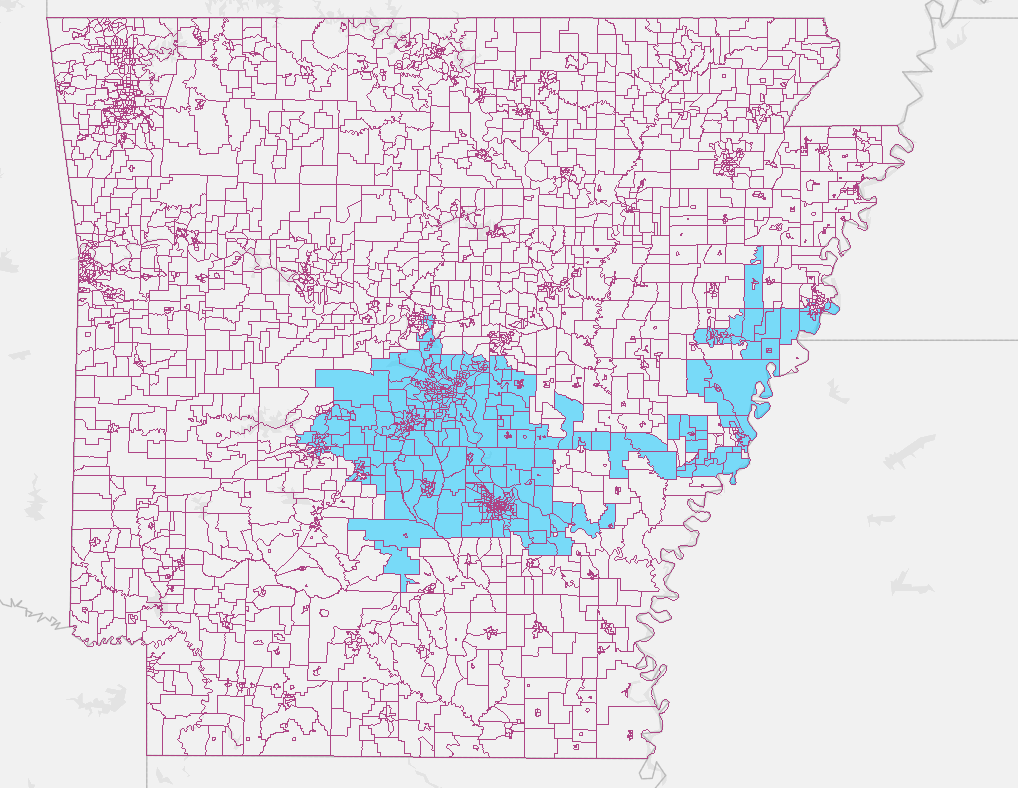

There are four House districts in Arkansas, and Democrats won 30 percent of the vote in House of Representatives races. That suggests they should probably be winning one out of four House seats rather than zero out of four. But the population structure of Arkansas means that the only way to make this happen is with an ungainly map.

In Massachusetts, it’s not possible to draw a map that doesn’t significantly underrepresent Republicans. It’s bad to let legislators manipulate democracy with gerrymandering, but it’s also bad to let weird aspects of geography rather than actual public sentiment determine election outcomes.

To say that Democrats’ representation in Arkansas — or Republicans’ in Massachusetts — should be a function of where in the state they are located rather than how many of them there are is silly. The best solution for most states is to treat the state as a single multi-member district with the seats allocated proportionally. California and Texas might need to be split into three or four districts and for Florida, New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, I could see a case for splitting into two or three. But the exact contours of the line-drawing just wouldn’t matter very much, no matter how unscrupulous the line-drawers are. It completely solves the problem.

Size doesn’t matter (much)

In a proportional system, the size of the House of Representatives would be a big deal. At the current size of the House, a state like Maine with two representatives is going to split 50–50 under basically any circumstance. Other small states, similarly, will end up with results that aren’t all that proportional, even under a proportional system, simply because it’s hard to divide a tiny number of seats in a proportional way. In this situation, I think there would be a strong case for House expansion so that even small states could have meaningful proportional representation.

But I hear House expansion proposed as a gerrymandering cure under the current single-member district system all the time, and it doesn’t make sense.

What’s true is that House expansion would reduce the tradeoff between proportionality and compactness in the hands of a good-faith map drawer. In other words, if you have no intention of gerrymandering, then it’s a lot easier to make a relatively tidy-looking map that also achieves partisan fairness if you have a huge number of seats to work with. This obviously isn’t the situation that we’re dealing with, though. The problem is that in an era of extreme partisanship and polarization, both parties are highly motivated to continue a tit-for-tat cycle of abuses that can’t be fixed by any realistic scale of expansion.

There are some separate, non-gerrymandering reasons to think that having more House members might be a good idea. But as an approach to fairer elections, it only works if you’re also doing proportional representation — a very good fix for the problem that happens to be outside the window of consideration for no particularly good reason.

Worth noting that multimember districts are illegal under the Uniform Congressional District Act. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uniform_Congressional_District_Act

Of course, Congress could repeal that. But it never will, because the status quo is advantageous for one side (the Republicans) while you'd need bipartisan support to change the law.

And it wouldn't be enough just to legalize multimember districts - even if you did that it wouldn't make sense for blue states to implement proportional representation unless red states also did it, which they wouldn't. You'd have to get Congress to not only legalize multimember districts but mandate them.

I will henceforth accept “likes” only from commenters in my district.