Presidential luck

Plus Villette, Iran, and AI functionalism

Kate and I went up to Maine recently, where we’ll be all summer, and this is, obviously, a great opportunity to learn about hyper-local housing politics.

For example, in the town next door, there was a proposal to subdivide an empty lot and build nine homes. This was the talk of the area last summer, when local citizens mobilized, dubbing the empty parcel “the Salt Pond Blueberry Barrens” and organizing to save it from the menace of nine homes. Lots of people who are not full-time residents, or even living in the town, participated in the anti-development move, so I sent an email to the relevant officials saying that I thought the housing was fine and would have a lot of benefits. But the forces of NIMBYism prevailed, and permission to build the homes was denied.

The semi-happy next step is that this week, it emerged that the NIMBY organizers have, in fact, gotten some money together to actually buy the parcel of land, offering $1.8 million, or “roughly twice the amount that Bowley paid for it in 2023.”

If that deal comes through, it will obviously not be a perfect process, and it won’t change the fact that coastal Maine is suffering from a serious shortfall of housing production. But I do think that “if the undeveloped land is important to people, it should be important enough for them to pay money for it” is a more constructive way to think about these issues.

Clearly, the natural beauty of the blueberry barrens has some value. But a lot of the problems with land use regulation are downstream of it being a way for people to impose large costs on others for cheap. To say, “Hey we really don’t want to mess up this view,” without quantifying exactly how much they don’t want to mess it up and whether that value is higher or lower than the value that potential residents would place on the ability to live there. People often portray land use politics as a kind of zero-sum battle between homeowners and renters. But this question of price mismatch is a reminder that it isn’t that — excess land use regulation is generally a value-destroying, negative-sum operation.

Benjamin J: How much should we weigh luck when measuring a President's success or failure? President Clinton, I think, was quite fortunate in his timing entering office at the end of the Cold War and presiding over the peace dividends which followed. Meanwhile President Hoover was particularly unlucky entering office right before the Great Depression. I would not argue Hoover was 'actually' a good President (or that Clinton was actually bad) but I feel people generally fail to consider context when examining records. Thoughts?

The story that I have always heard about Bill Clinton is that he will sometimes complain that he had the bad luck to govern in placid times, such that he will never go down in the history books as a “great” president who dealt with crises.

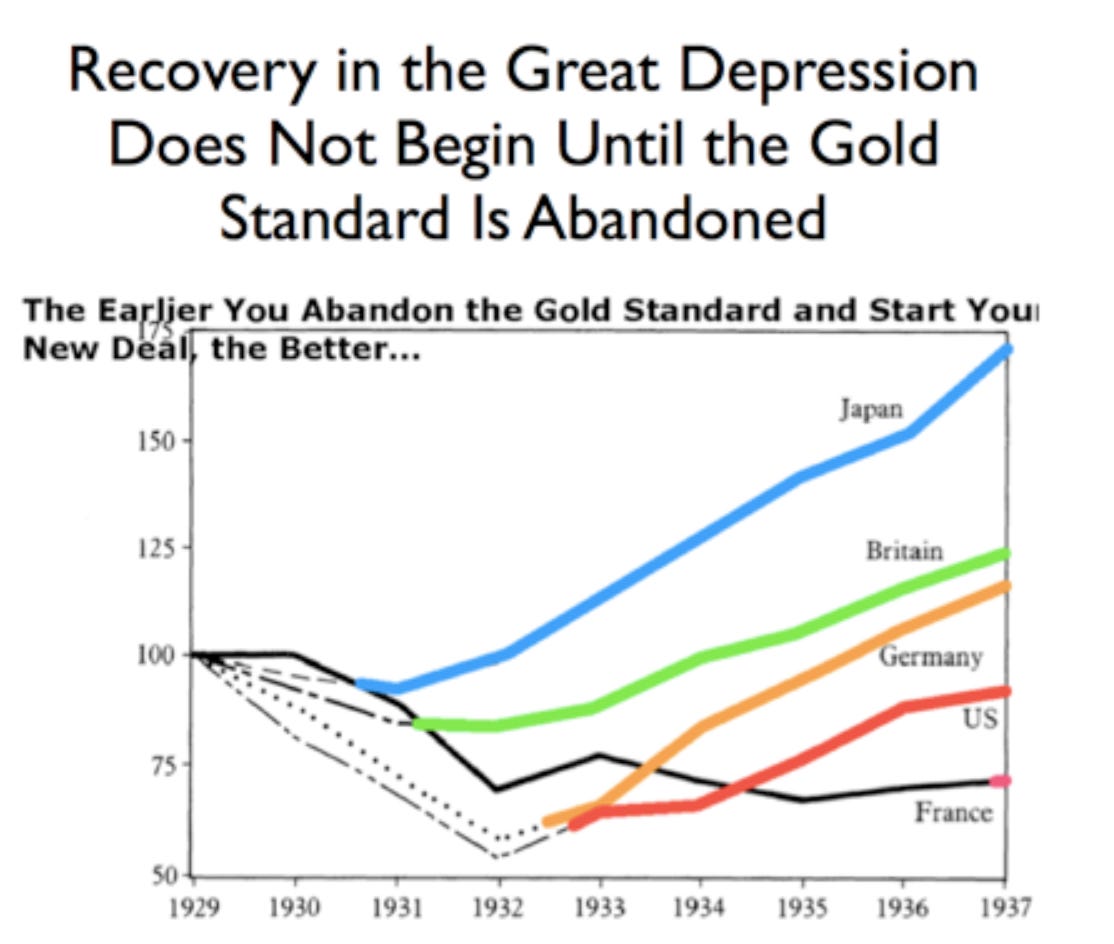

Similarly, while on some level Hoover clearly suffered from bad timing, it’s also the case that he badly mishandled the Great Depression. Countries like Japan, Britain, and Canada who exited the gold standard early and pursued inflationary policies saw early returns to growth, while the American economy kept shrinking.

FDR became a hero by improving on Hoover’s depression-fighting policies, but FDR’s policymaking in this regard was itself pretty flawed. There was ample opportunity for Hoover to act faster and in a more intelligent way than Roosevelt did. Even if Hoover was fundamentally committed to the gold standard and to avoiding significant deficit spending, there were proposals from economists like Jacob Viner, who shared those policy commitments, to generate the kind of reflation the economy needed. If Hoover had done that stuff, everyone would say that America was lucky to have had the incredibly talented technocrat Herbert Hoover — the guy who saved Europe from famine — at the wheel in the face of a huge crisis.

All of which is to say I agree with the point that you need to contextualize presidents with the actual circumstances that they faced. The substantive and political failures of the Biden era, for example, look a lot less bad when you realize that basically every post-pandemic leader ended up unpopular. That doesn’t vindicate Biden’s own flawed decision-making, but I do think it demonstrates that he was operating at a time when the degree of difficulty was high.

But I do also take the Clinton point seriously.

Because on some level, it’s not just that he wasn’t “tested” by a major global emergency, but that his historical reputation arguably fails to credit him adequately for being a prudent leader who kept things chill. There was a lot of political pressure on him at the time from Republicans to move toward regime change in Iraq. There was also pressure from the left and the center to do things like attempt a major military intervention in Rwanda. After the experience of the Bush administration in Iraq and the Obama administration in Libya, I think Clinton’s decision-making around those questions looks a lot better than his critics gave him credit for. Those are essentially questions of dogs that didn’t bark, though — he took passes on courses of action with large, hard-to-assess downsides. As a result, his eight years in office look relatively placid. To some extent, that’s luck. But to some extent, it reflects an appropriately cautious approach to some international issues, in contrast to, for example, Donald Trump’s decision to roll the dice on starting a war with Iran.

Dan Quail: Can you steel man the best case for bombing Iran? Do you think the administration has an endgame plan or is it just continuous flopping?

I don’t think the steelman case here is that hard to understand:

The Iranian regime is genuinely bad.

Israel has already successfully defanged Iran’s main regional allies and foiled their air defenses.

Bombing can be achieved at low cost to the United States.

The odds that coercing Iran through military force will compel them to agree to some kind of tougher deal than they were previously willing to agree to seem reasonably high to me — maybe even above 50 percent. If it works, Trump will look like a tough guy and a big hero who made a fool out of his nervous nellie critics.

The problem with this, in my view, is that the substantive upside to the United States of a tougher deal than what the Iranians had already put on the table is not that big, while the downside risks of the strategy not working are pretty large. One of Trump’s big things in life is willingness to take actions with very large downside risk that other more prudent people would avoid.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.