Politicians should talk to the press more

And reporters should ask better questions

I thought Kamala Harris might do a big press tour immediately after securing the Democratic Party nomination, just to draw maximum contrast between her energetic persona and Biden’s Sleepy Joe. Instead, she held a series of large rallies, harkening back to the heyday of Obamamania, which also draws maximum contrast.

It seems like a very successful strategy, but journalists, of course, like it when politicians do interviews. What they like even more, though, are informal press scrums. Big, formal interviews are normally conducted with a news organization’s most prestigious personnel, while “follow a presidential candidate around for months” is typically a somewhat lower-prestige job. But the “follow the candidate around for months” journalists write the bulk of the campaign coverage. The following itself can be tedious because even though a huge rally is thrilling if you attend it as a campaign supporter, it’s a little boring to see the same stump speech over and over again. What these journalists really want is a candidate who chats frequently with his traveling press tour, making amusing remarks and giving them something to write about. John McCain was the master of this and received glowing press coverage as a result.

Harris has done minimal scrumming, no press conferences, and no interviews, and the collective judgment of the press corps seems to be that this was fine while she was leading the VP search, but enough is enough. Even when Harris did do one brief informal scrum, what she got was a question about interviews.

This seems to me to be part of a downward spiral in political journalism. It is genuinely bad for the world that politicians increasingly prefer to communicate with the public exclusively through highly scripted or highly edited first-party media rather than engaging with serious questions. But it’s also true that the fundamentals of technology have shifted in a way that makes this strategy more viable. If the media’s countermove is just to bully politicians with the threat of negative coverage, all that happens is politicians’ supporters will become more receptive to freezing out the media. And that’s not what I want. I actually want to see Kamala Harris answer questions. But I think this involves both trying to convince elected officials that engaging with the press is a good idea, and also the press being more constructive in its own engagement so that doing an interview is a chance to accomplish something and not an obstacle course.

The world has changed

If you totally ignore politics and just look at the media dynamics around music, movies, or celebrity culture more broadly, you see this exact same thing happening.

It used to be that a handful of television networks controlled incredibly powerful audience communication choke-points, and then a bunch of newspapers each maintained a powerful choke-point in a defined local area. There was also a gaggle of magazines, each of which had a distinct audience. This meant that if you had a movie or an album to promote, you had to do what the people who controlled those choke-points wanted. You had to grant access to profile writers, and you had to say stuff to them that was juicy or funny or interesting. In the modern world, this just isn’t necessary. Major stars have their own social media channels through which they can communicate to fans in highly curated ways. Newer faces on the scene can build audiences the same way, and can also level up through association with more established stars.

This structural shift in power away from the media and toward celebrities has probably had some benefits — young women are no longer under intense pressure to go along with lad mag photo spreads or lecherous profile writers. It also means that everyone is “nice” all the time and rarely does anyone try to be incisive or interesting about art and culture, and that criticism itself as a vocation has withered in favor of recapping and fandom.

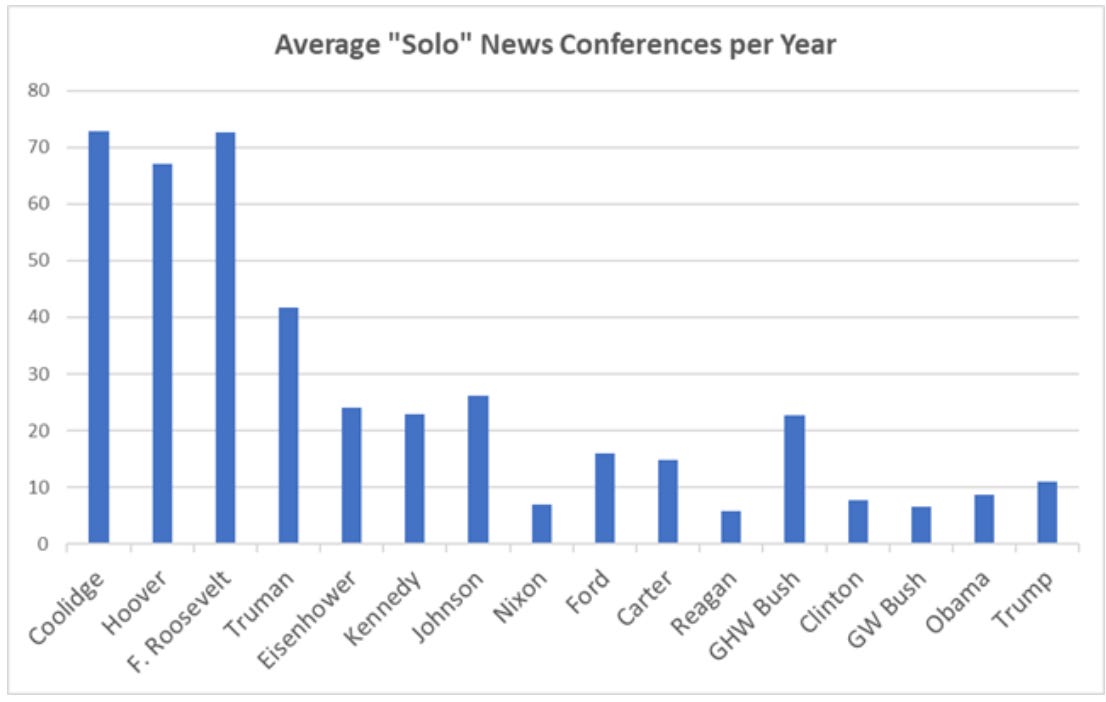

With politics, the public interest is different. But the point of talking about celebrity culture is to remind everyone that the roots of this are structural. Solo presidential news conferences have been in decline essentially since the rise of cable.

Trump has done a bunch of interviews as a candidate, but as David Bauder writes for the AP, that just means friendly interviews on Fox. And I think it’s important to note that these interviews are genuinely friendly, not just right-wing. When Trump sits down with conservative media, it’s not for extensive grilling about exactly which programs he’s going to cut.

What do people want from a Harris interview?

It seems to me that one big segment clamoring for Harris to do more interviews is left-wing people who are frustrated that they were denied a primary. As we recall from the 2020 and 2016 cycles, a primary is a good opportunity for the left to ask Democratic Party politicians to make electorally toxic public commitments that are then not enacted into law, precisely because they are so unpopular. Alternatively, if the candidates refuse to make these commitments, it gives them something to complain about. By skipping the primary, Democrats have gotten themselves a nominee that rank-and-file Democrats are enthusiastic about without her needing to do that. This is good for the cause of beating Trump, which is good for the cause of progressive policy, but a lot of left intellectuals don’t like that and want a chance to force her to be more specific.

To my way of thinking, this just recapitulates the bullying mentality from the mainstream press. In both cases, the idea is that you want a candidate to do an interview that’s not in their interest, so you make them an offer they can’t refuse by threatening to spend the whole campaign bitching and moaning about the lack of interviews in the hopes that shifts the balance.

I don’t think that this is a very appealing look. And I really don’t think it makes sense to refer to the millions of rank-and-file Democrats who think the basic policy contrast between the parties is large and who are therefore not that interested in the details and mostly want to beat Trump as “Blue MAGA.” They are correct! The basic policy contrast is large and the vast majority of Democrats don’t need to hear the answers to any specific questions to know that. They want Harris to do things that will help her win the election, which is a very reasonable thing to want her to do. Her job at this point is, in fact, to win the election.

Answering questions is a good idea

That said, I would like to make the case to America’s politicians that they have overcorrected to these structural shifts.

I am obsessed with the rapidly deteriorating popularity of America’s presidential candidates. In Gallup’s data, Mitt Romney was viewed favorably by 55 percent of the public in October of 2012. At the time, that was seen by the Obama team as an incredible success in taking him down a peg, because the only comparably unpopular figure was George McGovern, who was also at 55 in 1972. John Kerry was at 57 percent when he lost. George H.W. Bush was at 59 percent.

Those were the worst on record until 2016, when both candidates were at sub-McGovern levels of favorability, a scenario that recurred in 2020 and was on track to recur in 2024 until Biden dropped out.

Harris’ favorability is still incredibly low by any pre-2016 standard, but it has been rocketing upward for the past couple of weeks. And I think presidential candidates should aspire to achieving Romney/Kerry levels of popularity. As Republicans have attacked Tim Walz’ military record over the past week, people have naturally compared it to the “swiftboating” of Kerry. But by contemporary standards, John Kerry was a God-like political titan. This was the era of Fox News (and the height of Rush Limbaugh’s power), and Kerry was faced with a mainstream media that was way friendlier to Bush than they are to Trump, and his campaign was badly outspent by Bush.

I can’t prove that this decline in popularity is due to candidates overcorrecting away from real interviews, but I think the analogy to celebrity culture is telling.

Yes, media fragmentation means that contemporary stars are less reliant on media gatekeepers. But unless you are literally Taylor Swift, contemporary stars also just don’t shine as brightly precisely because of media fragmentation. Today’s hit television shows have a fraction of the audience of the big shows of the 1990s, and the “buzzy” shows aren’t the hits. Movies attract much smaller audiences, with diminished box office padded by premium formats with high ticket prices. All different kinds of media niches are occupied by micro-famous influencers (like me!) who seem important to people deeply invested in a particular niche, but who absolutely nobody halfway normal has heard of.

This seems like it’s working out great for Olivia Cooke, and you see voting patterns fragmenting badly in countries with proportional representation, but two-party politics in the United States is still about mass marketing. Holding giant rallies and maintaining a vigorous social media presence are both smart things to do. But those are almost by definition programming for the fans. How are you going to become broadly popular unless you speak to people who aren’t in the fandom, via outlets that they have confidence in, and try to address their concerns?

Interviews with upside

An old James Fallows observation, dating back to this 1996 piece at least, is that professional political journalists normally do a terrible job of mirroring the public’s actual curiosities about politicians. A group of people who cover campaigns for a living loves to ask campaign process questions. Asking Harris about when she’ll do interviews is a great example, or the infamous “What about your gaffes?” question shouted at Romney in 2012.

During Biden’s post-debate crisis interviews, he kept getting asked questions about the post-debate crisis rather than questions about the problems of the American people.

The intent of stuff like that is to be “tough” on Biden rather than ask him “softballs.” But in terms of the question on everyone’s mind as to whether he was up for four more years, directly asking him the question just isn’t revelatory. The reason the debate itself went so badly for Biden is that he seemed like he couldn’t handle really banal questions about inflation. Acting defensive about his age is easy mode.

This is why (again going back to the Fallow article) I think the “town hall” format is underrated. People in that format tend to ask politicians questions that are skeptical but that also comes from a place of genuine curiosity. They’re not trying to trip the speaker up or get into some kind of weird mind games with her. They are actually worried about something and want to hear the answer. It’s a risk for a politician because he might screw up and look like an idiot. But it’s also an opportunity to demonstrate something.

By the same token, I always wish reporters who got the chance to do these big-time interviews would take the chance to ask things they are genuinely curious about or that reflect concerns they sincerely believe the public has. In a generally very good set of polls for Harris, for example, The New York Times finds her up modestly in all three key swing states, with 44 percent of the public saying she is too liberal, 44 percent saying she’s just right, and only 6 percent saying she’s not leftwing enough. It would be good for the country for her to face some questions that get at this. But importantly, it would also be an opportunity for her! Of course, if she gives bad answers, she’ll look bad. But if she gets good questions that speak to widely held doubts about her and she gives good answers, people will find that reassuring. This doesn’t happen if a candidate insists on cocooning themselves in propaganda media. But it also doesn’t happen if interview-hungry journalists treat it like a challenge where the job is to shame politicians into engaging with the press and then attempt to embarrass them with gotcha questions when they do.

The current dynamic is dysfunctional, and the effort to browbeat politicians into doing more press isn’t working. But I really do think politicians are, on average, missing the boat here. Tim Walz worked his way onto a national ticket by doing a flurry of well-received television hits. The mayor of the fourth-largest city in Indiana became a major presidential candidate based on his interviews. In a healthy democracy, politicians will speak to the press — but the reason to speak to the press is that it offers a lot of upside, and journalists should try to structure our interviews to make sure that upside is there.

As a sports fan I can tell you: don't underestimate the role of journalistic laziness here. After every sports event, athletes (who are often required by leagues and contracts to sit for questions) are asked totally inane questions by reporters who often barely watched the game and gave no thought to what they might ask:

"Can you describe the emotion of this win?"

"Talk about that game winning hit."

I view process questions of politicians the same way. The easiest way to look like you are holding a politician's feet to the fire is to ask about their poll standing or something similar. Actually knowing what to ask on substantive issues requires the journalist do real work and research and preparation. They don't want to do that!

Media fragmentation means there are few or no viable places to do intervjews. No network news show has an audience of more than 7 million. No morning news show has an audience of more than 4 million. Most regular news viewers are politically engaged and already have their minds made up. Late night talk show audiences might be lower information and more persuadable, but no late night talk show has much over 2 million viewers.

This means that only a sliver of persuadable voters would see the actual interview. However, if there was a gaffe or a gotcha, it would go viral and would be all over the internet.