Don't give up on police reform

Catching and punishing cops who break the rules is possible and important

When video was released of Tyre Nichols’ apparent murder at the hands of Memphis Police Department officers, reactions were understandably strong.

Many of those working in this area expressed frustration that police reforms had done nothing to prevent Nichols’ death — that the fact that these officers were wearing body cameras shows that body cams don’t work, or that the officers are African American shows that descriptive representation among police officers doesn’t matter. D’Zhane Parker from the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation put out a statement bluntly saying Nichols’ death “affirms what we’ve known all along: Reform doesn’t work.”

My sense of things is that the people saying that kind of stuff are mostly venting. The footage was viscerally horrifying, and it’s frustrating that what seemed like a lot of political momentum for reform ended up largely running aground.

I didn’t want to start tedious policy arguments over these expressions of grief and grievances in an emotional moment. But I do think it's worth stepping back to point out that policing has changed a lot over the decades, mostly for the better, and there is good reason to believe that both body cameras and departmental diversity matter — and it matters that the perpetrators of this horrific crime were arrested and charged swiftly. Complicated systems are hard to change and American policing is likely to remain unusually violent by international standards as long as there are so many guns among the civilian population. But the United States is a very big country with a lot of police officers in a lot of cities having a lot of interactions with people, and changes at the margin make a big difference to people’s quality of life and even to who lives and who dies.

I think the past few years have shown not that “reform doesn’t work,” but that naive Overton Window tactics don’t generate reform. It’s a wheel-to-the-grindstone process where we need to identify and publicize good ideas and remind people who are fired up about the issue that change is possible.

Fifty years of police reform

One helpful source of information on the prospects of police reform, oddly enough, is Alex Vitale’s book “The End of Policing.” Vitale is a police abolitionist, and I did not find his book very convincing. To his credit, though, he notes that major changes for the better have occurred in the history of American policing, even though one of the themes of his book is the impossibility of reform.

Here’s Vitale:

America’s early urban police were both corrupt and incompetent. Officers were usually chosen based on political connections and bribery. There were no civil service exams or even formal training in most places. They were also used as a tool of political parties to suppress opposition voting and spy on and suppress workers’ organizations, meetings, and strikes. If a local businessman had close ties to a local politician, he needed only to go to the station and a squad of police would be sent to threaten, beat, and arrest workers as needed. Payments from gamblers and, later, bootleggers were a major source of income for officers, with payments increasing up the chain of command. This system of being “on the take” remained standard procedure in many major departments until the 1970s, when resistance emerged in the form of whistleblowers like Frank Serpico. Corruption remains an issue, especially in relation to drugs and sex work, but tends to be more isolated, less systemic, and subject to some internal disciplinary controls, as liberal reformers have worked to shore up police legitimacy.

The last sentence sums up radicals’ complaint about liberal reformers, which is not that reform doesn’t work but that it does. Major corruption scandals led to substantial reforms, and while those reforms did not eliminate corruption, they resulted in it being more isolated and less systemic in a way that bolstered the legitimacy of policing.

To most people, that’s good. Having widespread, systematic corruption in your city’s police department would be really bad. Having no police department would also be really bad. Successful reform is good!

Anti-corruption measures haven’t been the only successful reforms. Unfortunately the data on this isn’t great, but the data we do have strongly suggests that police departments used to kill young Black men at astronomically higher rates. Here’s a 2014 chart from the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice using CDC data that’s extremely relevant to contemporary debates:

In a more recent post, Peter Moskos assembled data that is more precise but less comprehensive and shows the same thing: there were many more officer-involved shootings in Chicago in the 1970s than there are in contemporary New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles combined.

So what happened? The details are complicated, but broadly speaking it used to be common understanding that cops could shoot and kill someone merely for non-compliance — especially if the someone in question was Black. When I was a kid there was a dark comedy titled “Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot” which was a spoof of the idea of police officers yelling “stop or I’ll shoot,” which in turn was based on a cultural and legal understanding that it would be legitimate to shoot someone just because he refused an order to stop.

A couple of Supreme Court cases in the 1980s changed the legal standard, and both before and after those cases, major American police departments were altering their policies.

These days if a police officer shoots someone, there is always an investigation. That doesn’t mean bad shootings never happen, and it certainly doesn’t mean that bad shootings are never successfully covered up. But investigating shootings as a matter of policy means that cover-ups are less likely to be successful. And more to the point, the routine investigations reflect a broad shift in understanding on the part of judges, police executives, rank-and-file officers, ordinary citizens, mayors, and city council members about what it is we want cops to be doing. And you can see in the numbers that this change made a very real difference.

Reforms need reasonable goals

Rep. Summer Lee appeared on Face The Nation on February 5 and said “to be very clear, police violence is crime. We cannot say that we care about crime but then do nothing, choose to do nothing, over and over and over when the crime is committed by a police officer. There are statistics that show that less than 2% of police officers who are engaged in misconduct are ever indicted at all.”

That’s a striking claim.

When Politifact investigated it, they spoke to Justin Nix, a criminologist at the University of Nebraska-Omaha. Nix says that Lee’s staff sourced the statistic to this German Lopez article at Vox. But the article doesn’t say only 2% of instances of misconduct lead to indictments. It says that less than 2% of fatal shootings lead to indictments.

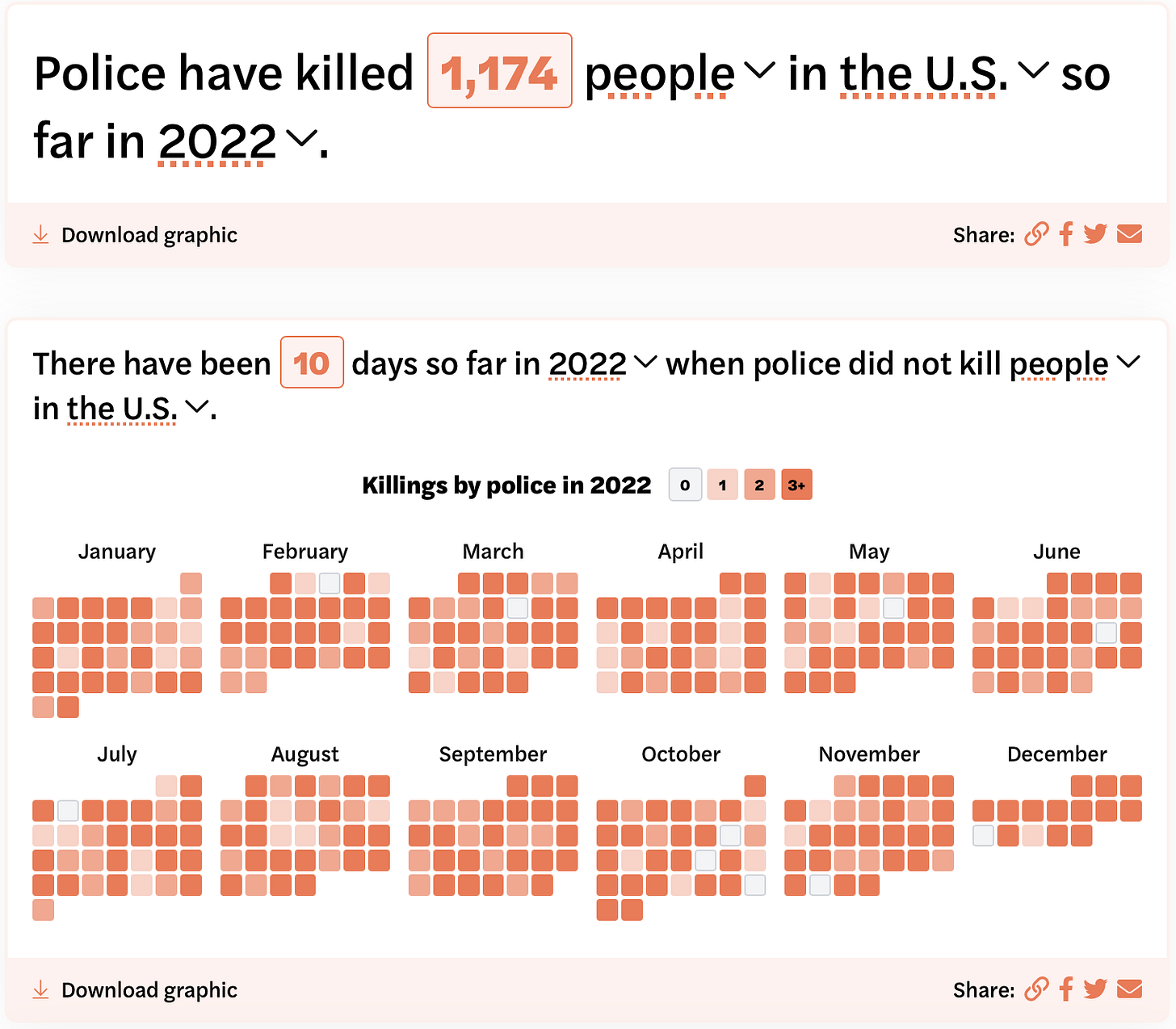

I think the confusion is the result of the rhetoric around “police violence.” Lee says that “police violence is crime,” and I think it’s natural for people to assume that when people talk about police violence, they mean by definition violent activity by police officers that is illegitimate. Lee is saying that this illegitimate police activity should be taken seriously as a crime and prosecuted. But looking at the statistics from the activist/data group Mapping Police Violence, they count literally every time a police officer shoots someone as police violence.

But some of the specific stories are like this December 28 incident in which four cops shot a man named Todd Jordan who arrived at Sidney Foodtown in Sidney, Ohio and tried to murder an employee. The official account claims Jordan refused verbal orders to surrender and instead “escalated the situation by brandishing a hand gun from his right side and raising it towards the officers.” It’s of course possible that the officers involved are lying or that the official account is somehow mistaken. That’s why it’s good that these days (unlike 50 years ago), all shootings — including ones that seem evidently justified — are investigated. But it seems a likely outcome here is that nobody will be indicted in this shooting because the police didn’t do anything wrong. The reason you heard a lot about Tyre Nichols but nothing about Jordan or most of the other people in the MPV database is that the Nichols case is not typical of acts of “police violence.” And lumping them together into a single rhetorical construct is somewhat confusing.

The question of whether body cams work hinges on what you’re hoping they will accomplish. Do body cams generate evidence that can inform the investigations that occur after police shoot someone? Absolutely. Did that contribute to the Nichols officers getting indicated? Yes. Did it stop “police violence” in the case of Todd Jordan? Well, no. If anything it’s the opposite — they released the footage and the shooting looks legit. As Vitale said of corruption, in this case the reform serves to “shore up police legitimacy” by demonstrating that they’re not just making stuff up.

In terms of fatal incidents, I think there are four distinct types we should consider:

Illegitimate police killings that are discovered and punished.

Illegitimate police killings that are covered up and go unpunished.

Police killings that are legitimate under existing standards but that activists think should be considered illegitimate.

Police killings that everyone agrees are legitimate.

A lot of discourse on this subject muddies the waters between two and three. Some of the incidents in the MPV database are like this one out of Virginia:

Around 1 p.m. on Monday, Dec. 19, deputies were dispatched to Thacker Road in Louisa County in an attempt to find a suspect wanted on a felony charge out of Orange County.

Upon their arrival, deputies were advised that the suspect — now identified as 35-year-old Michael Cline — was not at the location. According to authorities, the deputies were preparing to leave when they saw Cline running out of the residence. The deputies then reportedly chased after the suspect.

According to authorities, the deputies then used a taser on Cline, prompting him to produce a knife and run toward the deputies. A spokesperson with the Louisa County Sheriff’s Office said this caused the deputies to immediately fire their service weapons, killing Cline.

I have not read all the accounts in detail, but there are lots of cases of cops shooting guys with knives. That’s a far cry from the savage beating of Tyre Nichols, but I could imagine making the case that officers facing knife-wielders should be expected to bear greater risks to their personal safety. There are some pretty obvious possible downsides to that proposal (more cops would be injured or killed on the job, it would be harder to recruit and retain officers, the intensity of policing efforts might fall), but it doesn’t seem crazy to me.

But the reason things like body cameras or diversifying police forces don’t stop cops from shooting people armed with knives is that it’s not against the rules.

Policing the police works

Rachel Cohen wrote a good article reviewing the latest evidence on body cameras. The most up-to-date and precise studies suggest they lead to an approximate 10% reduction in police use of force. Whether that’s a lot or a little ultimately comes down to how much of the use of force you think is illegitimate. But people not only have different empirical estimates of what’s going on, they have different normative views about what is and isn’t legitimate. You can’t really blame the cameras for not having solved underlying social disagreement about what standards we are trying to enforce.

I thought the more important point Cohen makes is that cameras are integral to winning police misconduct cases:

“Without the body cam footage, we simply would have lost that case,” [civil rights attorney Christopher] Brown told me. “The officers all circled the wagon, saying that my client was fighting back, struggling, wouldn’t listen to commands. The video contradicts that, and shows he was not moving.” The family reached a $3.5 million settlement with Martinsburg following a seven-year legal fight.

Of the few convictions of officers that have occurred in recent years, nearly all involved body camera or surveillance footage.

This basic loop where you investigate what happened, have evidence, and punish people who break the rules works. And it works in terms of non-spectacular cases, too. A recent paper by Kyle Rozema and Max Schanzenbach in “American Economic Journal: Applied Economics” looks at what happens when police officers in Chicago face civilian complaints. They “find strong evidence that a sustained allegation reduces that officer’s future misconduct,” and through various tests, it seems that this is genuine improvement. Officers want to have good records to get promoted and advance their careers, and the desire to avoid getting dinged really changes how they behave.

I think some radicals are unreasonably skeptical of the efficacy of this basic cycle of obtaining evidence of misconduct and punishing it for the same reason they are unreasonably skeptical of policing itself — they don’t believe that punishing rule-breaking leads to better behavior. But we have a lot of evidence that it does. Policing reduces crime, and policing the police reduces misconduct. And I think it’s important to conceptually separate the benefits of routine monitoring of what police officers are doing from the impact of mass public outrage over a spectacular scandal. Roman Rivera and Bocar Ba find that while major policing scandals tend to lead to an increase in crime, routine increases in oversight lead to less misconduct and no change in crime. Tanaya Devi and Roland G. Fryer have a paper which similarly finds that viral scandals lead to an increase in crime, but lower-key federal investigations of police departments lead to a decline in the number of homicides.

Hard problems are hard

None of this is to say that reform is easy.

But I don’t think it’s futile. Policing has changed a lot over time and for the better. The most recent wave of reforms is bearing its own fruit in terms of accountability for misconduct. The problem of how to manage both public and police response to major scandals is a sticky one, but routine oversight appears to be genuinely effective.

It’s also important to be clear on what is hard about reform.

One issue is discouraging misconduct. Another issue is changing the definition of misconduct. This latter is hard not because of the technical aspects, but because you’d actually need to put in the time and effort to convince people that we should change the standards. Cameras and oversight boards and investigations and other reforms don’t “work” in this context because the point of cameras and oversight boards and investigations is to make sure everyone is following the rules — it doesn’t magically create a different set of rules.

Either way, whether or not cops follow the existing rules on the books is a big deal, and whether they can be held accountable when they break the rules is also a big deal. Reform is not hopeless on either score.

By the same token, diversifying police forces can’t solve all problems — in part because not all problems in policing are attributable to racism — but on average Black cops use force against Black civilians less often than white ones do. The banal conventional wisdom that some problems in policing are, in fact, about racial bias and that bias can be ameliorated by building more diverse police forces seems correct. The truth about all of this, though, is that if you want to bring different people into policing, you need to spend money and social capital on encouraging people to want the job. And if you want to hold officers to a higher standard of conduct, that’s going to cost more money, not less, because it’s putting more pressure on hiring and retention.

That’s all just to say that there’s a real conceptual fork in the road here: you can take the need for quality policing seriously and invest the time and money and effort to try to do it, or you can decide to ignore the history and evidence and throw your hands up and declare the whole thing hopeless. Unfortunately, I think the “throw your hands up” approach tends to do a better job of giving voice to the frustrations people feel in the face of the most egregious misconduct. But throwing your hands up never really solves anything, and the objective ought to be to make things better.

I was arrested for obstructing an officer in 2007. At the time, I was a young public defender and I had several clients who claimed they had been beaten by cops and then accused of attacking their assailants. Before body cameras, these cases were swearing contests, and most defendants in these situations pled guilty because they knew most jurors would trust an officer’s word over theirs.

On November 11, 2007, my wife and I were driving to our home in East Atlanta from a restaurant. Two of our neighbors were in handcuffs a block or two from our house. We passed by again 15 minutes later on the way to a friends house. They were still there and in cuffs. I thought my neighbors could use a credible witness, so I told my wife to pull over, got out, and approached the officer.

Officer: what are you doing?

David: watching you.

Officer: You are interfering with an investigation.

David: I am a member of the bar and I have the right to stand on a public.

Officer: I’m going to count to ten, and, if you don’t leave, you are going to jail

David: don’t bother, I’m not leaving.

I went to jail, posted bond and got out after three hours. The cop never showed up for court. This incident convinced me having a boss who might fire me for this kind of thing was a bad idea. I opened my own law practice 10 weeks later.

Matt's a bit vague on specific reforms here. I'll propose mine: federal law enforcement (probably the FBI) should investigate local law enforcement misconduct. We mostly can't trust local or state prosecutors to go hard on officer crimes, as they're all in a pretty tight-knit social & professional circle. Most of the big rule of law reforms of the 20th century involved the feds cracking down on petty state misconduct- the 'Mississippi Burning' cases where civil rights workers were murdered weren't exactly investigated by the Mississippi state police. Neither were the church bombings of that era, Emmett Till, etc.- in fact, local & state PD were outright violent thugs, beating & torturing protestors with impunity.

It's not as well-known, but the FBI is specifically commissioned to investigate local corruption- bribes, payoffs for real estate deals or liquor licenses, etc. This is based on the theory that if an alderman in say Chicago is taking some cash under the table, local prosecutors might be a bit conflicted in investigating him? Why not apply to this horrifically corrupt, violent gang of current Chicago cops as well?

A strong minority of cops today are legitimately bad human beings, who can commit terrible crimes with complete impunity. I think the knowledge that the FBI is waiting in the wings, watching their body cams, looking at bystander phone evidence etc. would be a huge step forward for the rule of law. Seeing as no one local would prosecute, say, the Buffalo cops who cracked open an elderly man's skull for no reason (1)- this is exactly what we have federal oversight for. Combine that with mandatory minimums for officer misconduct & mandatory use of at least medium security prisons when convicted I think should do the trick

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buffalo_police_shoving_incident