Polarization is a choice

Political elites justify polarizing decisions with self-fulfilling prophesies

When I was a young blogger, dinosaurs roamed the earth and political punditry was in hock to a perverse insistence that the stuff of workaday campaign journalism portrayed the critical factors shaping human events.

People would say that Michael Dukakis lost in 1988 because he had a bad answer to a death penalty question at a debate, whereas Bill Clinton won in 1992 because he came up with the clever yet cynical stunt of denouncing Sister Soulja. This kind of analysis would totally ignore the wildly altered circumstances of George H.W. Bush’s bid for the White House versus his re-election campaign. I think the plain truth is that if Democrats had nominated Clinton in ’88 and Dukakis in ’92, you’d have seen broadly similar outcomes and people would instead say that Dukakis’ “competence not ideology” pitch was successful in moderating Democrats’ image, while Clinton reminded people of Jimmy Carter. Or that Clinton was brought low by scandal and what ’88 showed was that personal character is really important.

The point is, structural circumstances matter a lot.

But I think current conventional wisdom has come to be too dominated by a style of political science fatalism that overcorrects into a kind of LOL nothing matters view of the world. Dartmouth’s Brendan Nyhan, for example, was recently chatting with some colleagues about the impact of Biden’s age on the race and remarked that “polls are close because we’re so polarized and public is still pretty down on the economy, which is actually performing strongly.” That’s probably correct as stated — polarization is a bigger deal than anything particular to do with Biden — but treating polarization as an exogenous fact about the political system seems like a mistake to me.

Polarization absolutely does have underlying structural causes. But it’s also shaped by deliberate choices that politicians and other political elites make.

And one choice people make that is leading to polarized outcomes is precisely the tendency to underplay the role of contingency and agency in political outcomes. If you’re convinced that deep underlying forces of polarization will assert themselves no matter what you do, you will make polarizing choices. In recent years, that’s been a predominant message from the media and from academics who’ve influenced media coverage. And so leading politicians — and to an extent primary voters — have made choices that re-enforce polarization dynamics. But they could make other choices.

Donald Trump’s lost moderation

Perhaps the clearest example of this is Donald Trump, who on Election Day 2016 was seen as a badly flawed candidate with a moderate ideology — more like Clinton, Gerald Ford, or Bush the Elder than Obama, Reagan, or W.

He lost that moderate image pretty quickly after taking office, and that’s because he didn’t do moderate stuff.

Interestingly, that pivot to the right involved him directly violating promises he made during the GOP primary campaign. In other words, it’s not that Trump “had to” pivot right in order to win the nomination. He ran and won saying that he would protect Medicaid (along with Social Security and Medicare) and tax the rich, but then he endorsed congressional Republican efforts to do the reverse.

And you saw something similar in the way he staffed his administration. Even though he clearly beat the party establishment to secure the nomination and largely won the general election without much help from the official GOP apparatus, in office he governed as a fairly conventional conservative who just really loved tariffs. Over time, he’s succeeded in bringing more and more of the conservative movement around to his indulgence of Russian nationalism, which is interesting but not really a gesture of moderation.

Anytime I bring this stuff up, people say it’s silly to act like the Trump phenomenon was or is about public policy. But I think that’s a fallacy. All the normal things people say about American politics of 2015-2023 are true. But these things are also true:

If Trump hadn’t pushed hard for ACA repeal and an unpopular regressive tax bill, Republicans would have done much better in the 2018 midterms.

If Trump had caved to Nancy Pelosi on additional Covid aid in the fall of 2020, he would have been re-elected.

If Trump had slid one slightly squishy Supreme Court justice onto the bench, the Dobbs decision would have reflected Chief Justice Roberts’ strategy of chipping away at abortion rights while minimizing public backlash, and Republicans would have done better in the 2022 midterms.

The Trump Show has many dimensions and the part where the star often does totally normal conservative Republican things is the least interesting part of the program, but it’s still important. And it’s important to recognize that this was not forced on him by primary voters; it reflects choices he made about alliances and staffing and his own personal priorities.

Joe Biden’s pivot to the left

Hillary Clinton faced a somewhat difficult structural situation in 2016. Barack Obama had been president for eight years, so public opinion had swung thermostatically somewhat to the right. The most politically convenient possible scenario for Democrats would have been to do something like the Reagan-Bush handoff in 1988, where the GOP nominated a successor who was broadly understood to be more moderate than his boss.

And if you go back to 2014, that seems to have been what Democrats were hoping would happen.

Not only did Clinton have high approval ratings back then thanks to a stint largely out of the partisan fray as Secretary of State, but she was broadly associated in the public imagination with her husband who had been more moderate than Obama. But Clinton felt a lot of pressure from Bernie Sanders’ primary challenge to position herself as more progressive than Obama, so she got to the incumbent president’s left on a range of issues before losing narrowly to Trump.

I think a natural lesson for the party to have learned from that was something like “we understand why this happened and it goes to show that winning three times in a row is very structurally difficult, but it was a tactical error.” You could also very easily imagine a world in which the party establishment takes that lesson but primary voters don’t, and decide to swing for the fences with a more ideological approach. But all throughout 2020, voters kept saying they were focused on electability and Biden ultimately got the nod based largely on electability arguments. Still, as Frank Foer recounts in his new book on the Biden Administration, “The Last Politician,” a broad swathe of influential party leaders decided during the Trump years that a leftward pivot was a good idea.

He’s talking here about Jake Sullivan but also a larger group:

An entire generation of young Democratic wonks, with a similar establishment pedigree, found itself in the same brooding mood, tinged with fear. They didn't worry about just Trump. They fretted about what would become of the Democratic Party. It seemed as though the party was fracturing, just like the nation. At Hillary Clinton's nominating convention, they saw the rage of Bernie Sanders's supporters- and it was directed at the wing of the party that had nurtured their careers.

Their elders were denizens of an old Democratic establishment that made a virtue of picking fights with the Left. To battle with Jesse Jackson or Robert Reich was regarded as evidence of political savvy and intelligence, since it required resisting the impulse of bighearted compassion and required consideration of the unintended consequences of social policy. But Sullivan and his cohort broke with their mentors and attempted to cultivate the rising Left. One of Sullivan's close collaborators on the Clinton campaign, the economist Heather Boushey, organized a reconciliation tour. Along with Mike Pyle, who left the Obama White House to work in finance, she put together a series of dinners in Washington, New York, and San Francisco. Young establishment wonks broke bread with Elizabeth Warren disciples, labor union officials, and intellectuals from left-leaning think tanks. At these meals, the establishment found itself gravitating toward an alliance — or rather a confluence.

A lot of this has been a healthy development. Bringing a bunch of Warren staffers into the administration helped forge very effective legislative coalitions in 2021-2022. The signature policy achievement of the Biden years — full employment — is a direct response to real failures of the Obama administration and reflects ideas I learned over the years largely from Boushey and her colleague Jared Bernstein. Some of it has been less good — I think this White House’s aversion to punching left slips into a tendency to avoid making choices among competing priorities in a way that isn’t tenable.

But the Democratic Party establishment was not overthrown in a massive grassroots rebellion, it wasn’t pushed aside by the abstract forces of history. Its leaders decided that the right lesson to learn from recent American history was that they should adopt more left-wing ideas about economic policy. At the same time, they were also shifting left on other things — whether that’s Biden reversing stances on Hyde Amendment or his now (rightfully) abandoned early pledge to halt oil and gas drilling on federal lands.

The micro and the macro

I think a political scientist would correctly reject “Jake Sullivan got to know Heather Boushey during the Clinton campaign, and then after Trump won, the two of them organized some dinners” as an explanation for broad ideological shifts in American politics. They’d say that kind of explanation is “journalistic” and they wouldn’t mean it in a good way.

But I do think it’s important to avoid completely retreating into abstractions about polarization. Specific people made specific choices.

I do think it’s true that the big picture matters more than the details. One challenge of preaching the gospel of moderation is that people tend to skewer you on the horns of a dilemma. If I stay abstract and say “candidates could generate a less polarized situation by moderating” I get challenged to name specifics. But whenever I name a specific, it gets dismissed as obviously too small to generate large effects.

That’s a clever debating move.

And I do think it’s true that if you think back to Bill Clinton, it’s borderline ridiculous to think there was some large mass of people who heard he denounced Sister Soulja and then voted for him for that reason. But here’s what did happen: Clinton made a strategic decision to position himself as more moderate than the average Democrat. A lot of specific calls flowed downhill from that, some of them substantive and some of them superficial, some of them attention-grabbing and some of them nothingburgers. And people did find out about the overall gestalt. Biden has, if anything, sought a public image that’s somewhat less moderate than the reality, based on the idea that coalition unity is the most important thing.

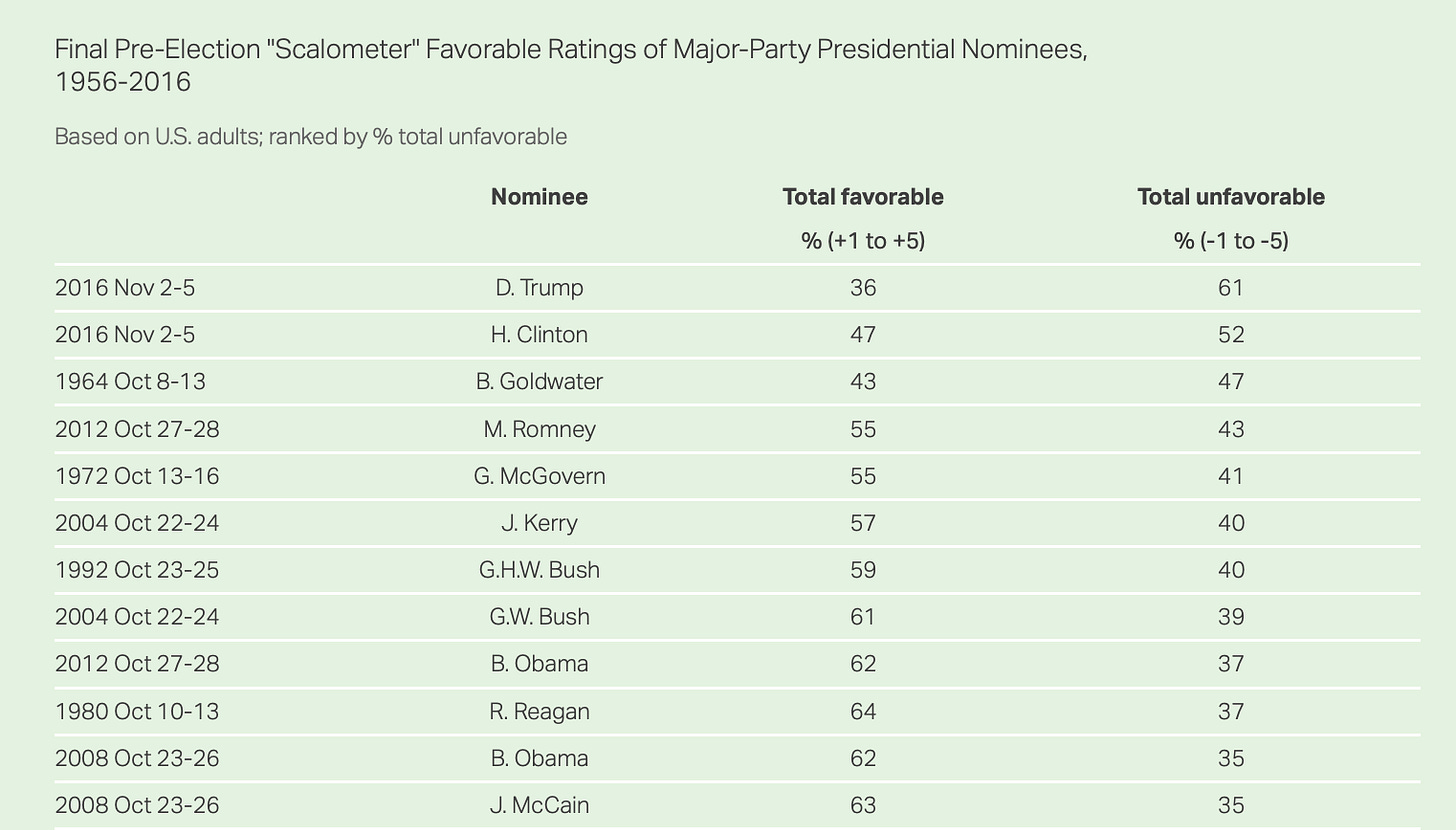

On the GOP side, lots of conservatives have convinced themselves that Trump’s scandals and misconduct are irrelevant because Democrats were mean to nice guy Mitt Romney. The truth, though, is people thought much more highly of Romney than of Trump — he just had the misfortune to face an even-better-liked Barack Obama.

There clearly are structural changes to the political process that weigh on all of this. But the fact is that 2012 was not that long ago. The conviction that ineluctable forces of “polarization” mean there’s no upside to trying to be more appealing on the level of either ideology or character helps to justify, incentivize, and validate specific choices that are themselves highly polarizing.

There’s a theory I’ve heard articulated somewhere that McConnell is actually the most brilliant politician his generation produced, in that he’s able to use razor-thin majorities to facilitate grossly partisan outcomes and then weather the backlash with minimal losses and no policy rollback, only to do it all again when he has another brief window.

Not sure I buy it in terms of brilliance; but I think it speaks to the “polarization is a choice” part of this. A lot of the elites of both parties are true believers and they use power in ways that are ideological when they have it. That prevents the formation of a durable New Deal-esque coalition because such a commanding majority needs to be an ideological big tent.

I've seen many Democrats on Twitter starting to get angry about Biden getting no credit for his economic focused messaging which they perceive as "moderate" because it focuses on kitchen table issues. I think this column gets at what it means to be perceived as moderate - you need to say something in the language of the other side. Trump 2016 clearly came out for gay rights and protecting social security/medicare in language Democrats used, and I think that got to left leaning independents in a way that swung meaningful numbers of votes his way. Just talking kitchen table stuff is not speaking in the right way to the right voters to be perceived as moderate (anymore).

What could Biden say or do that would be immediately understood by right leaning independents in their own language? I think there could be something on the border/asylum topic (press conference at the border highlighting the policy change requiring presentation of asylum seekers at ports of entry with a backdrop of border patrol officers?).

Interested if you all have other interpretations?