Moms leaving the workforce is a warning sign, not a revolution

It’s economics, not the culture war

I saw via social conservative Brad Wilcox a Washington Post report on falling workforce participation among working mothers. His eyeballs emoji indicates that he sees that as a promising sign of rising neo-traditional values. And indeed, the story says that “in some cases, mothers say they are giving up jobs happily, in line with MAGA culture and the rise of the ‘traditional wife’ (#tradwife on social media), which celebrates women choosing conventional gender roles by focusing on children instead of careers.”

The author of the piece, Abha Bhattarai, discusses other theories but largely stays within the values frame. For example, she quotes Misty Heggeness of the University of Kansas saying that women are essentially being pushed out of the workforce by return to office mandates and other right-wing social attitudes.

“It’s clear that we’re backsliding in the Ken-ergy economy,” says Heggeness, “that the return-to-office chest pounding is having a real ripple effect.”

I think that this is a bit too quick.

The labor-force participation rate for women in general and mothers in particular reached an all-time high during the Biden administration. And while in retrospect, one could chalk that up to pandemic remote-work policies or a general climate of wokeness, it’s worth recalling that, at the time, a lot of people were predicting the opposite. It was widely thought that the pandemic itself, by foisting more care responsibilities onto individual households, was going to crush women’s workforce participation. There were also widespread predictions that a “child care cliff” of expiring federal funding was going to send mothers back into the kitchen.

I also happen to be old enough to remember earlier iterations of this cycle, like the 2003 “Opt-Out Revolution” article that spawned endless rounds of discourse only to be followed a decade later by 2013’s “The Opt-Out Generation Wants Back In” and, of course, Sheryl Sandberg’s book “Lean In.”

What’s notable is that the discourse cycle largely moves in tandem with broader macroeconomic phenomena.

The year of the opt-out revolution, 2003, was also the trough of the post-9/11 “jobless recovery,” when even though GDP was growing after the dot-com bust, the economy continued to shed jobs. In 2013, the economy was rebounding from an even larger recession. Back in 2021 and 2022, the labor market was red hot as employers were scrambling to add staff while post-pandemic demand was roaring through the economy. Which is just to say that over and above shifting ideas about work-life balance and career versus kids, the labor market sometimes runs hot and it sometimes runs cool.

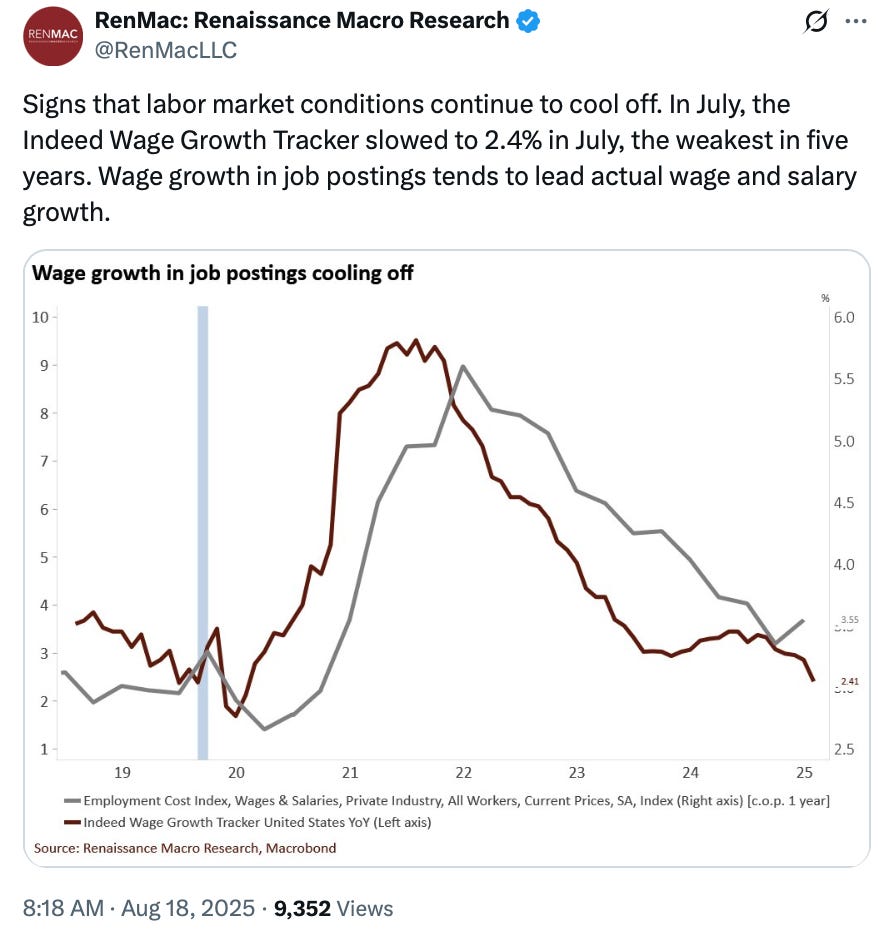

When it’s running cool, as it was in 2003, many women choose family over their careers. And when it’s running hot like in 2022, they lean in. And I believe that moms are now opting out in larger numbers not primarily because of the influence of Instagram tradwives or Ken-ergetic CEOs, but because overall labor market demand is weakening in the face of tariffs and other economic shocks.

How elastic is your labor supply?

The key concept, in economics jargon, is “labor supply elasticity.”

We know in theory that people are more likely to work if they can earn higher wages by doing so. But how much more likely? And how much higher do the wages have to be? That’s an empirical question. And we know the answer shifts according to different norms and circumstances.

Back in the day, the conventional view was that it was pretty easy to get teenagers to work for low pay during the summer when they were out of school. They had nothing better to do with their time and would readily take minimum wage retail jobs just to get out of the house and have a little spending money. But over the past 30 years, the quality of zero-marginal-cost entertainments (streaming video, social media) has gone up. There has also been a norm shift in high-socioeconomic-status households toward the idea that teenagers should do things that burnish their resumes for college applications.

As a result, teens’ labor supply has become less elastic. It’s not that it’s impossible to get a teenager to spend the summer flipping burgers, but on average, it costs more to tempt someone off the couch or out of the SAT cram class than it used to.

Teens aside, these elasticity questions typically come up because of interest in tax policy. Alcohol taxes not only raise revenue, they encourage people to drink less. Congestion pricing raises revenue, and also discourages driving on over-trafficked roads. A carbon tax raises revenue, and also encourages companies to pollute less. And an income tax raises revenue, but also encourages people to work less.

Unlike pollution, traffic jams, and getting drunk, working isn’t a social ill that we want to tax away — and someone is always ready to argue that taxing labor income causes people to stop working.

Society functions under the current tax code because, for most people at least, labor supply elasticity is pretty low. People complain about paying taxes because they like to have money, but they don’t actually stop working because they have to pay taxes. Conversely, when a tax cut passes, you don’t see people who already have full-time jobs running out to get a part-time gig during their off hours. There are a lot of empirical studies that show this, but again, you can tell that average labor supply elasticity must be pretty low because income taxes are pretty high and the economy continues to function. Prime age adults like to have jobs and incomes and money, and there are significant norms around a “normal” amount of work. But that’s the situation for most people; there are a lot of actual and potential edge cases.

Mothers have a more elastic labor supply

Many empirical studies look at the elasticity of labor supply with regard to taxes. And one thing they tend to find — whether examining changes induced by the 1986 Tax Reform Act or various enhancements to the Earned Income Tax Credit or policies in other countries — is a significant gender difference in elasticity.

As Costas Meghir and David Phillips put it:

Our conclusion is that hours of work do not respond particularly strongly to the financial incentives created by tax changes for men, but they are a little more responsive for married women and lone mothers. On the other hand, the decision whether or not to take paid work at all is quite sensitive to taxation and benefits for women and mothers in particular.

The basic intuition here is that a conscientious man who wants to be well-regarded will usually try to get a full-time job for the best available pay. He will, of course, prefer more money to less money. He’ll try to get a raise if he can and grumble about taxes. But the expected thing is to be working, so if he can find work, that’s what he’s going to do. For a married woman, a mother, or especially a married mother, expectations are different. The typical situation is a complicated series of tradeoffs between work and family responsibilities. For many women, there are people in their lives who will think less of them if they don’t work full-time, and there are others who will think less of them if they do. There’s no correct answer to these questions, just an endless series of thinkpieces about whether women can “have it all.”

As a result, the actual financial value of the job is a much bigger deal. And that means taxes can be a big deal. If you’re married to someone who makes $500,000 a year and you have a much more modest-paying job, you’re still paying a de facto 35 percent marginal tax on your income.

Of course, you could file separately instead, but because of the impact that would have on the higher earner’s tax situation, your family would end up worse off. At that 35 percent rate, it might not be worth your while to work. This is a completely gender neutral situation on its face, but in practice women are much more likely to be the partner earning less in this situation.

There’s a lot of sentiment among progressive tax wonks that, for this reason, we should get rid of joint filing. It is unlikely that the higher earner in my hypothetical couple would actually quit his job in response to the tax hike he’d face by being forced to file separately. And it’s possible the lower earner would stay in the workforce if taxed at a much lower rate. The idea is that this would be good for growth, good for revenue, good for gender equality (because again, women are more likely to be the lower-earning partner in this scenario), and could even let us get away with cutting tax rates.

Of course, the people who celebrate mothers dropping out of the labor force wouldn’t like the idea. But what I think is important here is that these findings from the tax literature also apply to broader labor market dynamics: The decisions that mothers make about whether to work and whether to do so full-time or part-time are much more heavily influenced by small changes in wages.

A warning sign, not a cultural revolution

It’s hard to know what will happen in the future, of course.

But I think the prior fizzling of the opt-out revolution and the general long-term finding about moms’ elasticity gives us pretty solid reason to believe that we are looking at deteriorating labor market conditions and not a huge revolution in values.

I am skeptical that the long-term trends toward delaying marriage and delaying childbirth are going to reverse. But if we do see that, then I’ll admit we are perhaps seeing a resurgence of traditional values and that’s what’s shrinking the labor force. But otherwise, the best explanation is that moms are experiencing roughly the same cross-pressures about work and family issues that they’ve been feeling for years, but the labor market is getting weaker, and so their choices are shifting at the margin.

One thing that makes this tricky is that we know ourselves and our own motives imperfectly. A person who drops out of the labor force to stay home with her kid can very sincerely feel that it wouldn’t have made a difference if she’d been offered a small raise three months earlier. But it can still in fact be the case that if she had been offered that raise, her decision would have been different.

This matters in part because of how unemployment statistics are calculated.

An unemployed person isn’t just a person who doesn’t have a job. It’s a person who doesn’t have a job and is looking for a job. So if you’re retired or a full-time student or a stay-at-home mom, you’re not unemployed.

This makes sense on some level. We’re trying to distinguish between people who are jobless for demand-side reasons (nobody is hiring) and for supply-side reasons (nobody wants to work). The problem is that real human decision-making is a lot more complicated than that. Mothers in particular make labor supply decisions in response to demand conditions, so part of a broad softening shows up in the data as “deciding to stay home with the kids” rather than a rise in unemployment.

My basic read of the situation is that:

Labor market demand is getting weaker, and moms dropping out is an early warning sign.

Inflation has been pushed up by tariffs and deportations, not by excessive demand.

Therefore, Trump should probably get the interest rate cut that he’s asking for.

The problem for Trump is that he’s committed to arguing that tariffs don’t push prices up, in which case there’s no reason for the Fed to ignore the recent rise in inflation. His team is also arguing (falsely) that the labor market for native-born Americans is booming, in which case it’s hard to know why you’d stimulate demand. And at least some conservatives want to argue that women dropping out of the labor force is them winning a cultural argument about values and preferences, not a sign of labor market slack.

There’s a kind of narrow propaganda logic to Trump’s lines on all of this, but also a real risk that sticking to the official story is going to lead them to ignore early warning signs that things are getting worse.

"There has also been a norm shift in high-socioeconomic-status households toward the idea that teenagers should do things that burnish their resumes for college applications."

AND College admissions officer who think a hour of Lacrosse is a better predictor of elite college-ness than an hour at American Eagle. :)

"There has also been a norm shift in high-socioeconomic-status households toward the idea that teenagers should do things that burnish their resumes for college applications."

I think it's even more that the idea of a 16 year old with a job and a car and their own money out doing what they want as an independent actor is just inconceivable. Even the idea of it is very dangerous. A 16 year old is a kid who needs constant control and can't be expected to make any decisions about his time or activities without intense parental involvement. And then kids end up crippled by anxiety as they have had no opportunity to make decisions on their own .