Members of Congress should actually live in DC

A plan to restore a measure of conviviality and increase productivity for our elected officials

In rural Mongolia, nomadic goat herders travel hundreds of miles by camel to reach their seasonal work sites. In the desolate winter, mine workers in Yellowknife, Canada drive a load of heavy construction materials over a precariously constructed ice road to reach their camps. And in the United States, members of Congress fly roundtrip between Washington, DC and their home districts on a weekly basis — some even sit in coach.

Obviously, our elected representatives don’t have the worst commute in the world.

But between the necessity of face time with their constituents and the general structure of the legislative calendar, members of Congress often find themselves on the road, with only a few days out of the week spent in Washington. That means less time to engage in committee hearings, take floor votes, and ultimately get to know their fellow colleagues, including the ones across the aisle.

Telling your voters that you want to spend less time with them isn’t the most politically advantageous decision. But I think Congress would benefit from actually living full time in DC and establishing more of a long-distance relationship with their constituents.

That doesn’t mean neglecting the district, of course. But restructuring the congressional calendar and offering members a stipend to move their families to DC could help deepen ties between members and foster an environment that accomplishes more legislative work.

Why members don’t live in DC

The New York Times recently conducted an interview series with departing members of Congress. And when they were asked how to fix the institution they’re leaving, Congressman Ken Buck and Senator Tom Carper both spoke fondly of a time when members of Congress actually lived in Washington, a time when, as Carper said, “Folks didn’t jump on an airplane on a Thursday afternoon and head for home.” Buck suggested that this resulted in “less divisiveness and less hate.”

Senator Carper and Congressman Buck are referring to an era that stretched well into the 20th century, when many members of Congress did, in fact, live in the city where they worked. Sarah Binder, a senior governance fellow at the Brookings Institution, told me that this was largely because there were smaller travel budgets and less demand for representatives to go back to their district or state. Of course, structural factors like the cost of housing in DC also play a deterring role. Which is why you sometimes hear interesting stories about elected officials pitching cots in their office or engaging in morally ambiguous decisions like renting an apartment from a lobbyist.

Newt Gingrich is another notable part of the equation.

After the Republican Revolution in 1994, Gingrich condensed Congress’ work from five days into three, so his caucus had more time fundraise in the district and less time to fraternize with colleagues on the other side of the aisle. Thirty years later, we’re still saddled with this legacy. Or, as Binder puts it, there is “increased pressure on members to be raising money and to be worried about re-election, which compels them to spend more time in the districts.”

The situation is particularly tricky for moderate Congress members, who are critical to bridging inter-party divides in the Capitol, contrary to the barriers erected by Gingrich. Yet, their tenuous position in swing districts subjects them to a skewed incentive structure that, as Binder notes, makes it politically beneficial to focus on local campaigning and constituency engagement.

The consequence of absence

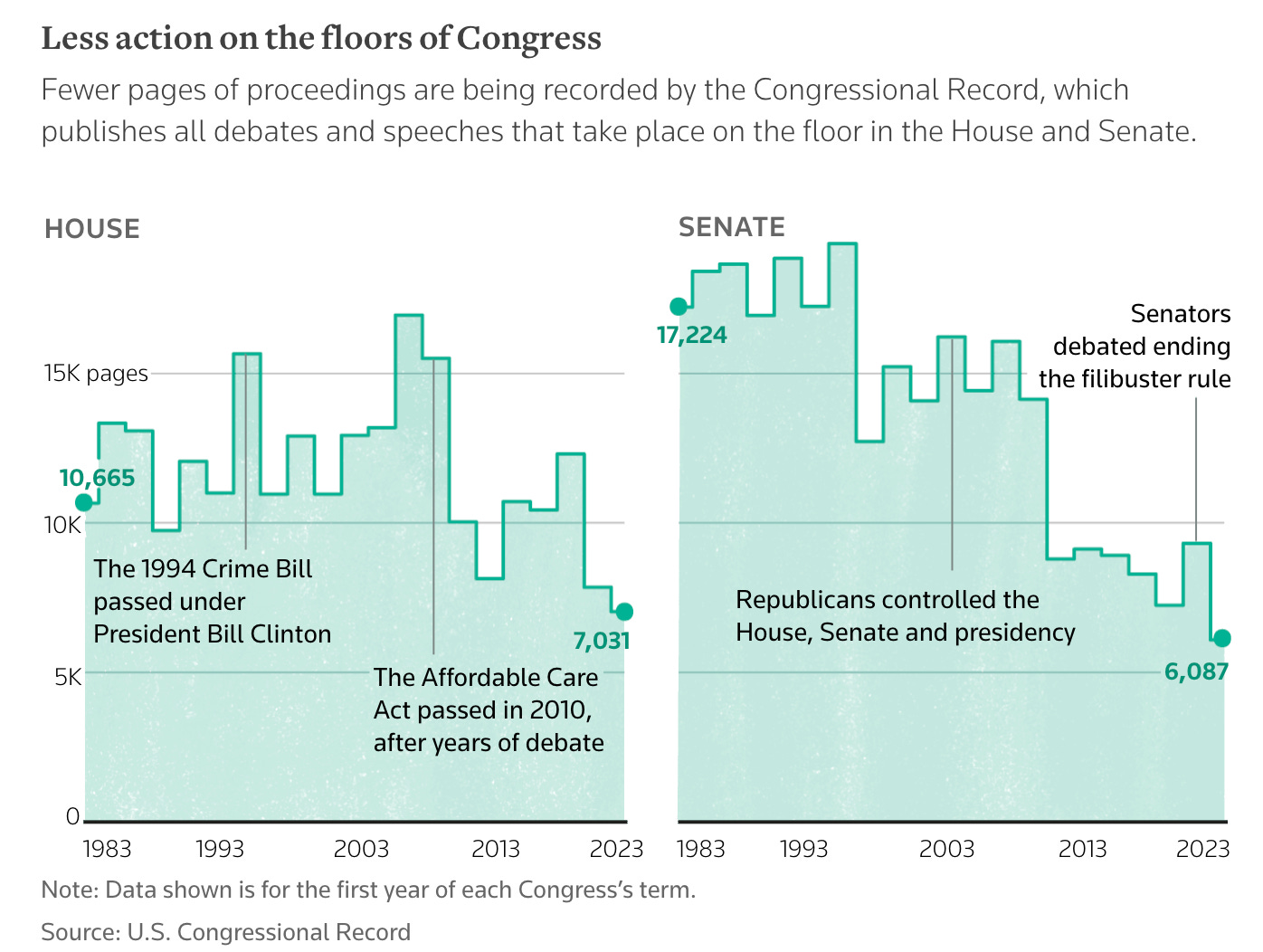

While Congress has accomplished some notable bipartisan legislative achievements, a recent Reuters report found that Congress is spending a historically low amount of time debating bills on the floor and sending legislation to the president’s desk. This is in part, due to the decline of bipartisanship and increase in polarization in Congress.

However, Michael Thorning, director of structural democracy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, also links this to the more limited time spent in DC. “Congress is not spending enough time in Washington to get the basics done,” he said, and the shorter schedule “really interferes with the one opportunity to interact with each other, to learn collectively, to ask questions of witnesses collectively.”

It’s not just the lack of time members have to spend on the floor; it’s also how little time they have to attend their committees and conduct important investigative work. In that same Reuters piece, Congressman Derek Kilmer puts it quite bluntly: “The dynamic that creates is members ping pong from committee to committee. It’s not a place of learning or understanding. You airdrop in, you give your five minute speech for social media, you peace out.”

This all combines to create a situation in which:

Members are generally too busy to spend substantive time with one another and develop deep inter-party bonds.

Members generally don’t have enough time to substantively debate legislation on the House and Senate floor.

Members generally don’t have enough time to conduct important committee hearings to inform their legislative process.

So what can be done?

Getting members to spend more time in DC

As the chair of the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, Congressman Kilmer considered a proposal to shift the amount of time members spend in DC. The Bipartisan Policy center also released a proposal that increases the number of working days in DC from 56 to 70 per year.

These are worthy starts, but I think we need to structurally change Congress’ relationship with DC. That means they shouldn’t live in their district and visit the Capital for work. They should primarily live in the Capital and visit their district to connect with their constituents.

To achieve this, Congress should first implement a schedule that mandates extended periods of collaborative work in Washington, D.C. Congressman Kilmer's proposal suggests starting at three weeks, though periods ranging up to eight to 10 weeks could be more effective. To maintain strong ties with constituents, these intensive work periods would be interspersed with lengthier recesses and enhanced support for district offices.

Moreover, to prevent members from leaving prematurely for weekends, legislative sessions could sometimes extend into Saturdays. These additional days would be dedicated to bipartisan activities designed to foster trust among members. There could also be opportunities for family visits to the Capital, further enriching this communal atmosphere.

That’s because families, of course, would be living in DC, too! When members are elected, they would be offered relocation packages commensurate with their family circumstance and the price of a proper house in the DC metro area. This is one of the most expensive housing markets in the country, so a starting package of $1 million, with additional bonuses for children, seems like a reasonable starting point.

Part of the goal here is to give our elected officials more time to conduct the important business of government. But more broadly, we need our members of Congress to develop the type of bonds that can only be forged through physical proximity. This meta analysis of 515 studies found that “intergroup contact typically reduces intergroup prejudice.” So by sharing the same place of worship, shopping at the same grocery store, or even having the same little league coach, we can deepen relationships between elected officials outside the polarized confines of modern day politics.

When talking about the idea with Professor Binder, she said that “Conceptually it might create the conditions for giving incentives to spend more time and expertise and in the business of legislation.” However, she did note that we still haven’t “broken that electoral connection that drives them to spend so much time back in their district.”

By all means, this shouldn’t be construed as a silver bullet. The institution is still riddled with issues and the incentive structure that sometimes forces representatives to worry more about campaigning than legislating, is still in place. Maybe you’re even satisfied with the work Congress has done as of late, and don’t buy that we need any systemic reform.

However, returning to the 20th century norm that keeps Congress members in the Capitol longer could help usher in a new era of political clarity and a more robust, effective policy-making machinery. Even if these benefits are still “conceptual,” they’re worth considering.

Visiting the district

Up to this point, the discussion has implied that the emphasis on legislators returning to their districts to keep in touch with voters is misplaced, and that they would be more effective if they spent more time in collaborative deliberation on national policies.

In part, this stems from a diverging theory of representation that was debated between the Federalists and anti-Federalists, but I think it was best encapsulated by the British politician and philosopher Edmund Burke in his 1774 speech to the electors in Bristol. There he said “Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.”

Essentially, I’m here to serve the country as a whole, not you whiny constituents.

It’s a terrible form of politics, and that’s probably why Bristol booted Burke after one term. But it’s a foundational theory that runs entirely afoul to one of the grounding principles of politics today — that representatives are elected to serve their constituents and their performance should generally be judged as such.

Of course, having members live primarily in DC isn’t a full-throated embrace of Burke’s theory of governance. That’s why the revamped congressional calendar would still include long breaks to visit home, along with more generous funds to ensure that district offices were properly staffed to handle constituent concerns and requests.

But in its current incarnation, I believe our political system places too much emphasis on the importance of Congressional members being physically in the district or state they represent. Furthermore, as constituents, it might be wise to remember that being in a long-distance relationship with our elected officials doesn’t mean they’ve forgotten about us; it just means they’re not bringing flowers every day.

Combine it with Matt’s YIMBYism - build a big building in DC with 535 units and make them all stay there.

I think this is a good idea conceptually, but will never be executed for the reasons you point out - it’s politically a bad look. I can already see the ad…

*ominous music*

“Member X hasn’t visited our district in months. Member X moved his whole family out to the DC Swamp. Member X doesn’t care about the district anymore. This November, tell Member X that if he forgets about us, we’ll forget about him.”

This message is approved by Candidate Y for Congress.

Will it matter that under the proposed rules Member X is required to stay in DC? Not at all!