Joe Biden's Cabinet isn't what matters

Personnel is policy — but cabinet personnel are overrated

Hump day!

Yesterday’s post about the minimum wage reminded me of the They Might Be Giants song “Minimum Wage,” so I thought I’d share it in case not everyone here is familiar with it. Part of the fun of a return to more blog-style content is the ability to be a bit whimsical even as our topics are generally pretty serious.

I also wanted to address something unfortunate that happened in the comments yesterday where a user was being repeatedly abusive, calling names and even using slurs. He’s been blocked from commenting for a week, will get a second chance, but is going to be put on an indefinite ban if that doesn’t work out.

I don’t have the resources or inclination to establish a rule-bound judicial-type process here — if you’re acting like a jerk, I’m gonna ban you. I think fairly aggressive moderation is the only way to make a comments section useful to the majority of people, and I want this to be a useful feature for paid members. So once again, many thanks for the support from those of you who’ve subscribed — it is truly gratifying to see. For those who aren’t yet sold, well, here’s hoping I change your mind.

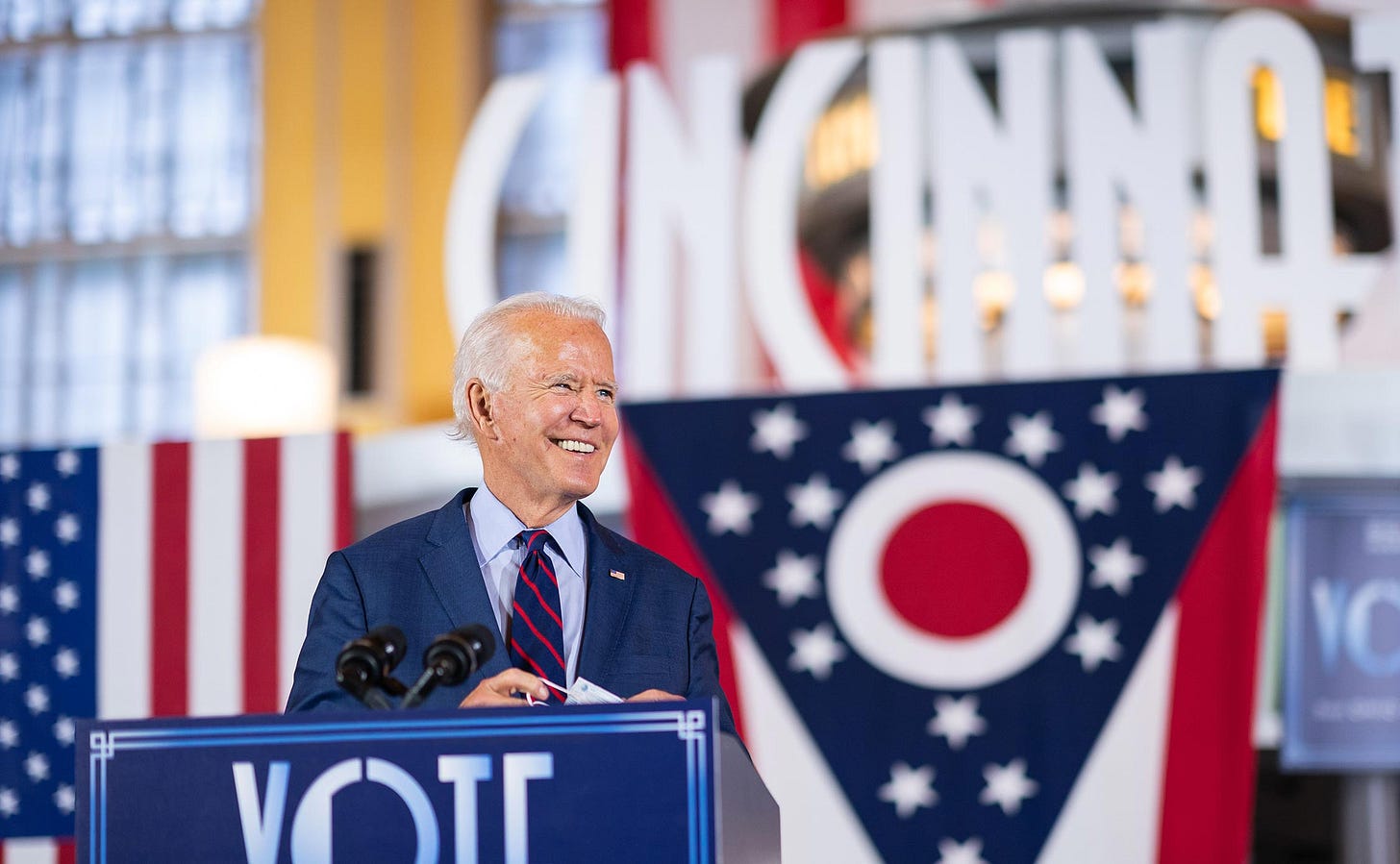

Today I wanted to talk about the Biden Administration.

Before Election Day I put in a fair amount of time in reporting on the wrangling over executive branch staffing in a Biden Administration and did an October 15 Biden Cabinet speculation article. I’ve been trying to keep up my reporting on this and thought about doing a speculation update. But while working on it, I realized that there are lots of these pieces floating around at places like Politico and Axios, all of which are pretty good. Instead, I think what people would really benefit from is an explanation of what well-reported Cabinet speculation stories are missing.

A few things to know about this:

Nothing is decided until Joe Biden actually decides, in consultation with Chuck Schumer (and/or Mitch McConnell pending the outcomes in Georgia). The transition teams and the vetters all have big impact here, but they can’t actually make a pick without the president-elect’s agreement.

BidenWorld contains multitudes. He’s been around a long time, and he’s not a particularly ideological person, so lots of people who are very genuinely “close to Joe Biden” or “Biden allies” or “a Biden confidante” just have different ideas and preferences about things.

This is exacerbated by the fact that precisely because Biden’s been around a long time, a lot of the people he’s closest to are quite old, whereas the high-level work in most areas is actually being done by a different, younger cohort of people.

There are a lot of interdependencies here. Lael Brainard, Tony Blinken, and Doug Jones are all strong contenders for Treasury, State, and Attorney General, but Michèle Flournoy is really the only contender for Defense. Are all four top jobs really going to go to white people? No. So if it’s Rice at State, that helps Brainard’s case. If instead it’s Roger Ferguson at Treasury, that helps Blinken. You need to see the whole field at once, which the people working on the individual jobs don’t always do.

Most important of all, though, is simply that I would encourage everyone not to get too invested in the symbolism of the Cabinet. Robinson Meyer, writing about climate change in the Biden Cabinet, recently pointed out that “in the Obama administration, the obstacles to climate action did not arise, in large part, from appointed energy or environmental officials. They came instead from Barack Obama’s political advisers, economic experts, and internal White House office directors.”

This is not a climate-specific phenomenon. The typical pattern in a Democratic administration is for at least some agencies (EPA and the Department of Labor in particular) to be run by stalwart progressives whose proclivity for activism is then restrained by the White House. It’s good to have good Cabinet secretaries rather than bad ones, but in terms of ideology and policy orientation, the most important factors are the president and whoever he chooses to actually listen to. The Cabinet secretaries are mostly middle managers or spokespeople, not the deciders you should pin your hopes or fears on.

The Cabinet matters less than you think

The single most important thing to know about executive branch staffing is that while the selection of Cabinet secretaries is obviously important, it’s less important than its prominence in public discussion would lead you to believe.

Policy is ultimately made in the White House (by the president, by the Chief of Staff, by the OMB Director who decides what people can ask to spend money on, and by OIRA which decides which regulations to promulgate), not by the Cabinet.

Cabinet secretaries can be important advisors, but the President and the White House senior staff can take (or ignore) any advice they choose. “Person the president listens to” is not an official job on the org chart.

Because Cabinet secretaries need to be confirmed by the Senate, oftentimes the president actually can’t get the person whose advice they most value confirmed (this happened to Susan Rice under Obama), so the job goes to someone else.

Because the Cabinet is so high profile, the question of who gets these jobs tends to reflect a complicated mix of considerations (gender and ethnic diversity, ideological balance, rewarding party stalwarts), of which “does the president listen to this person?” is not always that high on the list.

Last but by no means least, Cabinet secretaries typically do not have the power to hire and fire their key subordinates. Those subordinates are nominated separately by the president, confirmed separately by the Senate, and they serve at the pleasure of the president. So while the Department of Justice plays a key role in antitrust enforcement, it’s not obvious that the Attorney General’s view of antitrust issues has much causal impact on what the Antitrust Division actually does.

A further issue is that what Cabinet agencies actually do is often not exactly what you might think.

I remember a discussion with a subcabinet member in HUD during the Obama administration when he said to me wistfully, “the problem is we don’t have a lot of authority over housing policy.” Later in Obama’s term, Julian Castro moved to ban smoking in public housing, which is not really housing policy but potentially did save a lot of lives. That’s sort of how it goes at HUD. You have a lot of authority over public housing which lets you do some interesting public health things, clean energy things, and lots of other things that involve making rules for a finite quantity of structures. But at the end of the day, HUD has very little influence over how mainstream housing policy works.

I also recall a conversation with a person who rose to a very senior level in the Commerce Department in which she recounted being a little surprised and frustrated by the extent to which her job just involved preparing for the Census rather than anything to do with economic policy. Democratic energy secretaries (like Steven Chu) generally want to work on renewable energy, while Republican ones (like Rick Perry) want to promote oil. But a huge share of the department’s budget is actually about nuclear weapons. Ernie Moniz was a rare Energy Secretary who was actually into the nuclear weapons portfolio and became very influential around the Iran deal.

At this point, thanks to Trump, people largely realize that DHS is mostly immigration and border stuff and not actually some kind of elite counterterrorism squad. Veterans Affairs invariably goes to someone associated with the military, but the job is basically running a large hospital system. But in almost no case is the Cabinet secretary actually setting the direction of policy.

Focus on the White House staff

It’s hard to overstate the extent to which practical policymaking power has come to be concentrated in the hands of the White House staff.

There are a bunch of reasons for this, but the basic reality is that while Cabinet secretaries can be very important, they are roughly as important as the White House staff wants them to be. If Pete Buttigieg is Secretary of Veterans Affairs, but the White House communications shop wants him on television frequently defending the administration position on the main issues of the day, then Secretary Buttigieg becomes one of the most high-profile members of the administration. No past VA Secretary has been like that, but it’s not a rule. The White House can do whatever they want.

On a technical level, the most important jobs are Chief of Staff (who can speak for the president and thus boss anyone in the government around), National Security Advisor (who runs the “interagency process” on national security issues and thus has enormous influence on what actually happens), and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) director. The OMB is important because it has visibility into every agency across the whole federal government. The OMB also contains the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), which in most cases needs to approve any regulation any agency wants to do. Read that OIRA sentence again because it’s important. On regulatory issues, the agencies propose but OIRA disposes, so in a practical sense it is this office rather than the EPA or the Labor Department that sets the limits for regulatory activism.

The other White House jobs are also very important, but their scope is somewhat ill-defined.

There is a National Economic Council, which in some theoretical sense is supposed to be the economic policy equivalent of the National Security Council but isn’t really.

There is a Council of Economic Advisors, which sounds redundant but is traditionally more academic.

There’s a Domestic Policy Council, which handles policy issues that are neither national security nor economic, whatever that might be.

You can also just create various “czars” to coordinate policy — Biden’s designated chief of staff, Ron Klain, was “Ebola czar” at one point, meaning he got the different agencies working together and sorted out disagreements between the relevant people.

The main thing here is that when you’re talking about the Executive Office of the President (EOP), formal titles are not that informative. There are three actual ranks of EOP staffers: Assistant to the President, Deputy Assistant to the President, and Special Assistant to the President, which is the worst even though it sounds coolest. These ranks tells you something about a person’s salary and/or the general esteem in which they are held.

But the real power of these jobs amounts to something more nebulous — does the president take your advice? Do other people in the government believe you speak for the president and should be deferred to? Are you trusted to communicate the administration’s views to the public? To Congress?

To make this concrete, progressives really don’t like Bruce Reed, who was a major anchor of the right flank of Bill Clinton’s administration and later became one of Biden’s chiefs of staff as VP. There will be pressure from the left to not give Reed a job with a fancy title that sounds important. But what the left really fears is Joe Biden taking Bruce Reed’s advice. But it doesn’t really matter what Reed’s job title is — if he’s in the White House and Biden wants him in X, Y, and Z meetings, then there he is in the meetings. Jared Kushner’s waxing and waning influence in the Trump Administration hinged on his relationship with his father-in-law, not on formal job titles.

The place where formal titles matter most is in the oft-neglected world of independent commissions.

Independent agencies matter a lot

Back in the Progressive Era, there was a vogue for creating bipartisan commissions. These typically have five commissioners; each party’s Senate leader picks a commissioner, each party’s House leadership picks a commissioner, and the President picks a fifth commissioner to serve as chair. SEC, CFTC, FTC, and FCC are the most important ones in my opinion, but there are more.

This has not really turned the commissions into the non-partisan technocratic bodies that the Progressives were hoping to create. But it does mean that the independent agencies are less under the thumb of the White House staff.

The president can't just fire the commissioners except for actual misconduct, so to an extent they can go rogue.

The structure of the commissions means that if Biden taps a solid progressive as Chair and Chuck Schumer names a solid progressive for his slot, but Nancy Pelosi picks an industry lobbyist for her slot, then the one industry-friendly Democrat can team up with the two Republicans to block things.

Independent agency rules generally are not subject to OIRA approval.

So while these alphabet soup agencies sound tedious, this is an area where the specific names chosen is fairly important.

SEC and CFTC regulate different aspects of financial markets, and there are some creative ideas floating around about using SEC power to advance climate goals as well. The FCC is in charge of communications — mostly phone, cable, and TV companies, but conceivably important aspects of the tech industry. The FTC has a kind of weird dual mandate over antitrust issues and consumer protection issues that makes it very important for the technology industry.

I have not heard or read anything credible about any of these jobs yet but watch this space — as I say, this is what really matters.

Subcabinet jobs can matter a lot

As with the Cabinet members themselves, the panoply of undersecretaries and assistant secretaries and so forth are starkly limited in their policy independence from the White House. But the conventional focus on Cabinet secretaries does, I think, end up tending to underrate certain subcabinet jobs.

When Hillary Clinton agreed to serve as Barack Obama’s Secretary of State, one of her conditions was that she be allowed to select her own subordinates. A consequence of this is that I know of people who got blackballed from service in the Obama State Department for the sin of having worked for Barack Obama during the 2008 primary. Because it wasn’t really the Obama State Department, it was the Clinton State Department.

But for that exact reason, the Clinton arrangement is pretty unusual. NOAA is part of the Commerce Department and the Federal Railroad Administration is part of the Transportation Department, but the Commerce Secretary and Transportation Secretary don’t get to hire and fire the NOAA or FRA administrators. A normal person isn’t going to get spun up about NOAA or the FRA anyway. But if there is some specific issue that you care about — labor unions and freight train operators are locked in a years-long battle about staffing levels on freight trains — then you want to focus on the specific agency that oversees the issue.

There is also just a lot of asymmetry across Cabinet departments that defies easy summary. The subcabinet positions in the Defense Department are important because DOD is so huge, but DOD itself at least approximates a unitary institution in which the Secretary exerts leadership over the civilian side of the military. Commerce is way on the other side of the spectrum, where it’s kind of a hodgepodge of agencies without much happening at the Commerce Department per se. HUD is much more unitary than Commerce, but one of the most important parts of HUD — the Federal Housing Finance Authority, which oversees Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — is basically its own thing.

I personally like neat and tidy diagrams and sometimes dream of reorganizing these agencies in a more rational way. But realistically, it’s not going to happen.

So who’s going to be in the Cabinet?

After all this, of course, all anyone wants to know is who will be in the Cabinet.

But there’s a huge known unknown: the special elections in Georgia. If Democrats win both seats, then Kamala Harris breaks ties in the Senate, nominations are not subject to filibuster, and Biden can appoint a Cabinet that looks like this:

Defense: Michèle Flournoy (former Undersecretary of Defense for Policy)

Treasury: Lael Brainard (on the Fed Board now, former Undersecretary of Treasury for International Affairs)

Attorney-General: Xavier Becerra (California Attorney-General) or Doug Jones (former prosecutor, soon-to-be-former senator from Alabama)

State: Susan Rice (former National Security Advisor)

Homeland Security: Alejandro Mayorkas (former Deputy DHS Secretary)

Health and Human Services: Michelle Lujan Grisham (Governor of New Mexico)

Education: Mark Takano (current House member, former classroom teacher)

Labor: Julie Su (California Labor Secretary)

Veterans’ Affairs: Pete Buttigieg (former mayor of the forth largest city in Indiana, but you know…)

HUD: Keisha Lance Bottoms (Atlanta mayor)

Energy: Arun Majumdar (founding director of ARPA-E)

Transportation: Eric Garcetti (Los Angeles mayor)

Interior: Deb Haaland (representative from New Mexico)

Commerce: Terry McAuliffe (former Virginia governor)

Agriculture: Heidi Heitkamp (former North Dakota senator)

That would be by some margin the most diverse Cabinet in American history. It’s majority female, including the first-ever women to serve at Treasury or Defense. It features two openly LGBT people, beating the previous record of zero. It’s majority non-white. It also consists exclusively of people who are well-qualified for their jobs and well-liked in the Democratic Party. Progressives would not be thrilled with these picks, but they’d live with them. Moderates, similarly, will feel this is okay. Mostly it involves the chips following where they inevitably will — progressives want an Agriculture Secretary who’ll take on factory farms and a Treasury Secretary who’ll break with the whole Clinton/Obama era of economic policymaking, but those aren’t plausible asks from Joe Biden and a 50/50 senate.

The problem is that if Democrats lose the Georgia senate races, then we’re in unknown territory and all this speculation is off. Republicans think it’s important to have a functioning Defense Department and don’t have a problem ideologically with Flournoy, so she’s still in at Defense. But beyond that, all bets are off. Does Mitch McConnell care if HHS Secretary is vacant for Biden’s entire administration? Probably not. Does the governor of New Mexico want to quit her job to be “acting” and participate in a lot of lawsuits over whether or not her appointment was legitimate? Probably not. I think the journalists who are telling you how the divided government scenario is going to work are getting out over their skis. McConnell doesn’t want to say “if Loeffler and Perdue win, America will face a non-stop constitutional crisis,” because that would not be helpful to their election prospects. And Biden doesn’t want to say it either because he wants to put a brave face on and do his transition without admitting that he may be governing from a position of crippling weakness.

But I think it might be true. The good news is the Georgia races are very competitive, so my best advice to anyone who fears “non-stop constitutional crisis” is to send some money to Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock.

I've moderated a few decent-size communities, so let me make the case for not giving second chances to users like that one:

Your goal here is to have a functional and productive community. A lot of that comes down to the most thoughtful 10% of commenters. It is very easy for someone who is obnoxious to drive off people from that 10%. By contrast, even if the obnoxious person gets reformed they're probably never going to be top 50%, much less top 10%. The benefit of giving them a second chance is that they might get better and stick around, but you probably don't want them to stick around even if they do tone the assholeishness down a bit. And the cost is the very high risk of driving away other, better people.

Also, there is basically zero chance that a user who leans in to being an asshole is going to be mollified by a temporary ban.

Remember, there's a human instinct towards forgiveness, but kicking someone out of your newsletter's comment section doesn't mean they aren't going to eat.

At FCC, former FCC Commissioner Mignon Clyburn gets Chair if she wants it (last name sound familiar? She’s Rep Clyburn’s daughter). Current Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel (Dem) gets it if Clyburn declines. That’s the word about town in communications circles.