Janet Yellen's mistake

A look back at the 2015 interest rate increase

Hello folks, happy Monday.

This is a holiday week obviously, and on a normal holiday weekend I anticipate Slow Boring taking some time off, but this is our debut month. It’s also an unusual Thanksgiving since my family and I aren’t going anywhere or doing much. So there will be a brief item Thursday morning, giving some thanks, and on Friday, in lieu of a normal article, I’m going to publish the Trump Wins pre-write that I wrote and which never ran because it didn’t happen. I think it’s an interesting piece even though, obviously, the actual election results went a different way.

Today I want to talk about Janet Yellen, who is increasingly rumored to be in line to serve as Joe Biden’s Secretary of Treasury.

Janet Yellen is a great economist with an extremely strong academic record. She was the second woman to chair the Council of Economic Advisors (under Bill Clinton) and the first woman to chair the Federal Reserve (under Barack Obama), and after speculation had long centered on Lael Brainard, Yellen has now emerged as a likely candidate to be the first woman to serve as Treasury Secretary.

She’s unquestionably well qualified for the job, she’s extremely well liked by everyone who’s worked for her, and there seems to be a sense in the Biden Universe that she’d be supported by both the progressive and centrist wings of the party in a way that Brainard wouldn’t be. That all makes sense, and I do think that if Biden picks her, few will want to criticize what would be an extraordinary capstone for the career of an extraordinary woman. Nobody has ever held the CEA/Fed/Treasury triple crown of economic policy jobs, and it would, among other things, create an incredible situation in which her husband George Akerlof is clearly the less professionally distinguished member of the couple even though he has a Nobel Prize.

But I want to be a spoilsport and talk about a mistake Yellen made as Fed chair.

Skanda Amarnath, Director of Research at Employ America, told me, “Yellen has garnered a reputation for being dovish but her actual track record is far more mixed. The US economy was slowing down in 2015 as a result of overseas weakness. But while other members like Lael Brainard had flagged the downside risks, Yellen and Vice Chair Stanley Fischer were more eager to set the stage for a series of hikes.”

She eventually reversed course on this, and the bad call was not necessarily all that consequential. But the basic issue is one the Biden administration will likely face again: how do you assess whether the economy is at full employment? Yellen and much of the Obama Administration got it wrong, and it would be good for Biden’s team to do better than this next time.

The federal funds rate, explained

The Federal Reserve does a lot of things, but one big thing that it does — really the thing that it does in normal times — is try to steer the economy by manipulating something called the federal funds rate.

If you don’t know what that is, don’t worry. Most people don’t know, and even if you did understand it in detail it wouldn’t sound important. The reason is matters is that all the different interest rates in the economy are connected. They all tend to move up or down together at the same time. The federal funds rate happens to be the one the Fed manipulates most directly. But the point is that all the interest rates tend to change when the Fed tweaks the federal funds rate.

In the Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan eras, economists developed the view that manipulating this one interest rate should be basically the only thing the government does to stabilize the economy. A panel of experts would look at the numbers, and if unemployment was too high, they’d cut the federal funds rate. Of course, if you keep it too low for too long, you’ll get inflation and need to raise the federal funds rate. This was so boring and technical that you could ideally keep politics out of it and leave the mass public to just trust that the Fed knew what it was doing.

The way this worked in practice was that Greenspan cultivated and received a reputation as “The Maestro” of the economy, which is of course sharply in tension with the idea that these are technical decisions made according to a neutral body of expert knowledge.

More to the point, look at what happened during Ben Bernanke’s eight years as Fed Chair — the federal funds rate went down basically to zero, but unemployment was still high.

This is a dumb problem for a comprehensive technocratic solution to the problem of economic stability to have, but in the conventional framework interest rates can’t go below zero because you could always obtain a zero interest rate by storing cash in a safe. This turns out to be not quite true since safes aren’t free and transferring large quantities of physical cash is annoying. But it’s at least approximately true, and for better or worse, Bernanke did not want to experiment with a negative federal funds rate.

Instead, a bunch of other stuff happened (including fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing), and macroeconomic stabilization is now firmly ensnared in politics.

Bernanke was originally appointed to the Fed in 2006, and Obama reappointed him in 2010 as a kind of reassuring gesture of bipartisanship. All throughout that second term the unemployment rate fell, but slowly, and the federal funds rate stayed at zero. Bernanke did not go for a third term, and Obama ultimately replaced him with Yellen.

Yellen’s 2016 interest rate increase

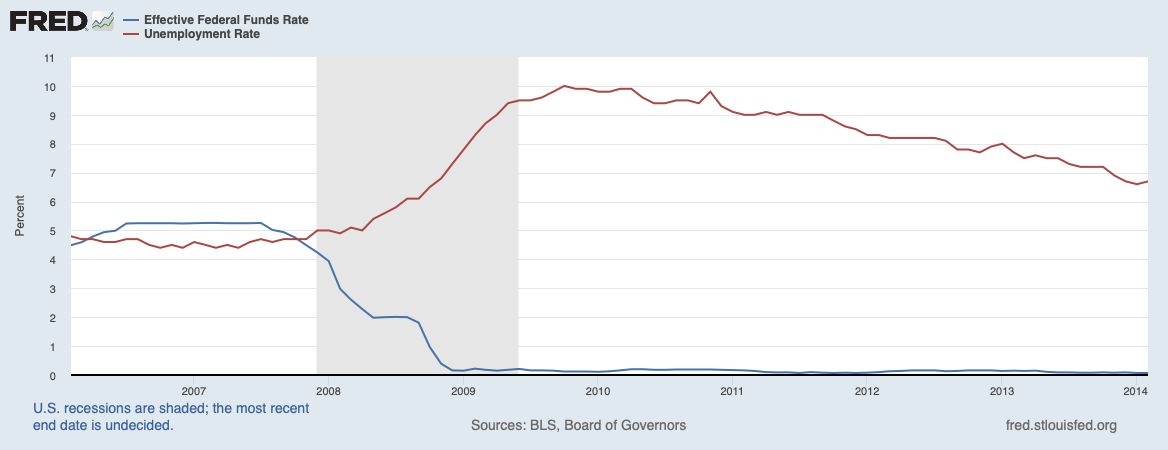

If you look at unemployment during the Yellen-Obama years, it’s basically the same story as it was under Bernanke: going down slowly but steadily.

The federal funds rate is different, though, because the Fed lets it rise at the end of 2015 and then does it again a year later.

Why do that? Well, nobody ever promised that interest rates would stay at zero forever. And by the time Yellen did it, the unemployment rate wasn’t so high anymore.

But on the other hand, the reason you are supposed to raise interest rates is because you’re worried about inflation. And inflation at that time was not high. This graph shows the inflation index the Fed targets, both including and excluding food and energy prices. You can see clearly that at the time of the hike, both were well below the two percent target rate and had been for some time. The all-in inflation rate was rising pretty fast, but that’s because energy prices were finally recovering from a huge collapse in the winter of 2014-2015. And the more stable rate that excludes food and energy prices had simply been chugging along below target for a while.

So why do it? I am not a mind-reader. The Fed’s stated reason was they wanted to head off the possibility of hypothetical future inflation, which does not make much sense.

But it was clear from talking to staffers at both the central Fed and some of the regional banks at the time that leadership was impatient with the zero interest rate situation. It went against their sense of how things ought to work. They did not want to crash the economy. But they believed the economy was strong enough to withstand higher interest rates, so they were determined to implement them as soon as possible, rather than waiting as long as possible to maximize job growth.

Tying these two ideas together was the notion that the economy was close to full employment.

The labor force participation debate

As you may or may not recall, during Obama’s second term there was a lot of disagreement about the labor force participation rate.

To be unemployed you need to be looking for work. And during the Great Recession and the slow recovery, a lot of people stopped looking for work. So as the unemployment rate became low, some people argued that the depressed labor force participation rate was a sign that the economy was still far from full employment. Casey Mulligan, a leading conservative economist, wrote a book called The Redistribution Recession which argued that the Affordable Care Act and other social programs had eroded people’s incentive to work. Business leaders often suggested a “skills gap” was to blame and suggested new training programs as the fix.

Obama’s economic team looked at this and concluded that the issue was mostly just that there were more old people around. But they also viewed a small and shrinking share of the issue as “cyclical” (i.e., more stimulus would help) and a growing share as a “residual” mystery that they were determined to explore.

At the time I had multiple occasions to ask them if this mystery residual wasn’t just also cyclical effects and maybe the Fed should commit to keeping interest rates low.

But that was not really their view. They were focused instead on the idea that things like criminal justice reform or modernizing unemployment insurance and improving skills were the key.

It was really just cyclical

Now some of us argued at the time that you could tell we were still suffering from demand weakness because wage growth was still slow. Get to full employment, we said, and wages will start to rise. And as wages rise, participation will go up and companies will invest in training. Eventually, the wage increases will cause price increases and we’ll see inflation, and then we can raise interest rates.

Yellen acknowledged this argument in a September 2017 speech but did not buy it:

In that regard, some observers have pointed to the continued subdued pace of wage growth as evidence that the economy is not yet back to full employment. As shown in figure 8, labor compensation as measured by the employment cost index has been growing at more or less the same rate since 2014, and hourly compensation in the nonfarm business sector —a quite noisy measure, even after smoothing—is actually growing more slowly. But growth in average hourly earnings and the Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker have clearly picked up.

In addition, productivity growth has been quite weak in recent years, and empirical analysis suggests that it has been holding down aggregate growth in labor compensation independent of labor force utilization in recent years.

So what happened? Who was right?

After a whole year of steady job growth in 2016 and then another one in 2017, wages finally picked up in 2018 and were really chugging nicely in 2019.

This was the “good economy” of the Trump years. If you look at job growth or GDP growth, the Trump Economy and the Obama Economy look identical. But if you look at wages, there is a very real acceleration under Trump that became the basis for Trump’s strong polling on the economy as an issue. Labor force participation, meanwhile, was ticking up during these years despite the aging — exactly as us demand theorists had predicted.

The Trump years happen to be an unusually good case because we know he didn’t manage to repeal the ACA or the Dodd-Frank Act. So the stuff conservatives said was holding back participation can’t have been the reason. But he also didn’t overhaul job training or anything. Job growth just kept chugging along (and the budget deficit went up because Trump cut taxes while congress increased both military and domestic spending). And we could have had that full employment economy years earlier with better macroeconomic policy.

Biden needs to do better than Obama

Now let’s be clear about something — the single rate hike Yellen oversaw in 2016 is not the reason the labor market recovery was sluggish. It was one hike, it was small, and in the grand scheme of things it was not a big deal.

But it’s analytically significant simply because it was clear cut in terms of the policy tradeoffs.

The best thing would have been to get more fiscal stimulus going all the way back to 2009-2010. But that conversation quickly gets mired in political finger pointing.

The Fed eventually did multiple rounds of Quantitative Easing and should have done them sooner, but they were all controversial.

There were a bunch of other unorthodox monetary policy steps that might have helped, but there was no clear consensus about which of those tools would be best to use.

The rate hike, by contrast, was simple. Conventional wisdom said the Fed should and would do it, but if the board had decided not to, nobody could have stopped them. And there were no big theoretical questions about the impact. It was simply an empirical judgment that the economy was closer to full employment than it really was. Not a judgment that Yellen and her colleagues were unique in making by any means, though they just happened to be the ones in a position to make that call.

But that’s why it matters for Cabinet purposes.

Most of the great minds in the Democratic Party economic firmament made the wrong call about the state of the labor market in 2015-2016, and there was a cost to that. It’s very important that the Biden administration show better judgment about these questions, not least because it has a huge impact on what approach you take to negotiating with Republicans. If after a strong vaccine-induced rebound in 2021, Biden decides we’re near full employment in 2022, that militates toward “grand bargain” type negotiations aimed at a smaller budget deficit. But if we’re in a situation similar to 2015-2016, the right approach is to do stimulative deals that trade tax cuts for spending, get the economy back to true full employment, and get wages ripping.

There’s more to life than owning Larry Summers

Something worth saying about all of this is that a big hidden driver of the politics of the Treasury selection is what you might call the ghost of Larry Summers.

Summers, if you don’t know, was a well-regarded academic economist who become Chief Economist at the World Bank in 1991, then was brought into the Treasury Department by Robert Rubin during the Clinton Administration, then became Treasury Secretary at the end of that administration, and ran the National Economic Council at the beginning of the Obama administration. Between presidencies he was briefly president of Harvard. Summers also has a long association with the hedge fund D.E. Shaw and has cashed a lot of speaking fees from a lot of private interests.

A fair amount of factional infighting in Democratic Party circles consists of efforts by progressives to displace Rubin, Summers, and members of the Rubin/Summers coaching tree from their positions of power and influence in the party.

Summers was initially considered the leading contender to replace Bernanke at the Fed, but a revolt against him led by Elizabeth Warren ended with Yellen getting the job instead. Warren’s problem with Summers was really about bank regulation and sexism, not monetary policy or macroeconomic stabilization. There were whispers at the time from Summers’ camp that he would in fact be a more dovish, pro-worker monetary policymaker than Yellen, but that did not carry the day. During Yellen’s time as chair, Summers did stake out a more dovish view, but there were whispers from his detractors that was just him being a jerk and jockeying for more influence. Then when it looked for a while like Warren might become the Democratic nominee, Summers went nuclear against her and the wealth tax.

What does this have to do with anything? For a long time, the leading contender for the Treasury job has been Lael Brainard, who is currently on the Fed board, who disagreed with the interest rate hike, and has generally displayed an excellent track record.

But Brainard is seen as a Summers protégé, and the left has been quietly slamming her for months. The preferred progressive candidate was Sarah Bloom Raskin (a former Deputy Treasury Secretary) who moderates seem to dislike for no particularly clear reason. Yellen has risen to the top of the pile as a kind of difference-splitting candidate.

My cautionary note on this whole mess is there is no actual evidence of any significant ideological disagreement between these three women about anything Treasury has authority over. To the extent that there is daylight between them, it is that Brainard was more dovish on monetary policy than Yellen five years ago. If you forced me to guess, I would tend to think that indicates that Brainard would be more amenable to aggressive fiscal stimulus than Yellen today. But that might not be the case. Fiscal and monetary issues are different, the circumstances are different, and people change their minds. Raskin has a very low public profile, and I don’t think anyone knows what she thinks about anything. My personal inclination would be to keep Brainard where she is for now to avoid creating a new Fed vacancy, and then appoint her to replace Powell as chair when his term expires.

Most of all, though, I don’t think it’s wise to flatten all of economic policy disputes into a single ideological axis defined by people’s personal relationships with Larry Summers.

Remind me to take some economics courses, so I can contribute intelligently.

Pretty much the only thing that I feel like I have a dog in the fight in, is the discussion about skills gaps.

That’s a conversation I would like to see in depth.

I actually have a bachelors degree in computer programming, Igot it in the Air Force, because I figured it would help me with whatever I do.

But my job is blue-collar, skilled technical, working with Welder’s, pipefitters, millwrights, engineers.

I make more money than programming, because it’s harder for companies to find skilled technical labor than it is computer programmers.

My 21-year-old daughter, got pregnant and had a baby earlier this year, single mom (Not a brag, just made a mistake and we are pro-life in a non-force on others way).

She had already failed out of college, studying the normal liberal arts stuff.

She knew she had to do something, so we sat down and talked about her options, re-what skills are really needed to survive, and thrive.

She ended up choosing, at my encouragement, a mechatronics program (Fixing robots on automated systems) at the local community college. Equal parts electronics, electro mechanical, hydraulic, and coding.

She is absolutely loving it, and, this is brag, she has the top grades in the class, despite some of her class meets already working in related field.

She fully expects to get a job starting out making 30 bucks an hour. Amazon is building one of their super distribution centers right beside the school. They are already bugging the school, saying they need more technicians to help them maintain their robots.

Her class cohort consists of 13 people. Nowhere near enough to satisfy the demand. There are probably 50 times at number of local students who are in rolled in normal academic programs at schools in the area who will probably fail. Many of these, would have success in programs like my daughters.

Part of the skills gap, is cultural. We tell all these kids that they need a college degree to be successful. Or they need to learn how to code. But there is a big gap, where the economic activity actually happens.

And quite simply, a lot of talented students are getting lead wrong.

Skills follow economic activity, but the presence of skills also help companies decide where and what to do. China is so strong in technical production because even as wages rise there, they have access to the technical expertise needed for these areas.

I dictated this whole thing on my phone. Apologize for any grammatical and punctuation mistakes.

I really don't understand why the Fed is consistently so focused on coming in just short of 2% inflation. Like, if your goal is really 2% over the longer term and you're consistently coming in under, why not just keep monetary policy loose until you're really at 2.5%+ for multiple quarters and THEN raise rates. A year where we exceed a 2% target isn't going to kill us.

Sometimes I wonder if my view would be different if I had lived through 70s, but it feels like there is this excessive fear of even just slightly above target inflation.