It's not just Biden

Incumbents everywhere are unpopular and losing elections.

Joe Biden’s current polling is bad, and there are a lot of theories as to why.

I have some theories of my own, but relevant context for any theory is that Justin Trudeau’s polling in Canada is much worse. That could support a story about how political currents in the Anglophone world are tilting sharply against progressives, perhaps a backlash to wokeness and the welfare state. But a Conservative Party is in office in the UK, and their polling is, if anything, even worse than Trudeau’s. Back in October, New Zealand turned out their governing center-left party and the right scored a big win. But in the spring of 2022, Australian voters kicked out a conservative incumbent government and brought the center-left to power.

Which is to say incumbents have been losing across the English-speaking world.

The partisan politics of Ireland are a little hard to characterize, but right now the country is governed by an unusual coalition of the two main parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. The grand coalition is currently polling at a combined 37 percent, and if an election were held tomorrow (which it won’t be — it’s not scheduled until 2025), there would probably be an unprecedented Sinn Fein government as a result.

I’ve been tempted, based on this kind of casual empiricism, to assert that Biden’s bad numbers are a part of a nearly universal pattern in which every incumbent government is either unpopular or else already lost an election since the big inflation wave of 2021-2022. A more systematic review of the evidence (done with help from Maya) shows that’s not exactly correct. But it is approximately true. And I think it supports the view that the global fundamentals are just ugly for incumbents.

Voters wanted the end of the pandemic to mean immediate restoration of 2019 economic conditions, but that was not possible. And even in places where the rate of inflation has come down, people are still bitter about what transpired.

A vast global tide against incumbents

I think it’s useful to look at who has won re-election in 2022 and 2023:

Viktor Orban was re-elected in April 2022.

About a week later, Emanuel Macron was re-elected in France, but it was the best-ever result for the opposition National Front, and Macron’s party lost its majority in parliament.

In Portugal, a center-left minority government faced a crisis because left-wing parties wouldn’t back its budget proposal, and this led to an election in which a lot of left voters defected to the center-left, giving them a majority.

Pedro Sanchez’s center-left government in Spain lost its majority in July of 2023, but after months of talks, he was able to stay in power by making a deal with small separatist parties.

In Denmark, Mette Fredericksen’s coalition of progressive parties lost power, but she stayed on as prime minister by forming a grand coalition with some center-right parties.

The key thing is that out of these five, really only Hungary and Portugal represented strong results for the incumbent governments. By contrast, we’ve had clear turnovers of power in Australia, the Czech Republic, Israel, Italy, South Korea, Sweden, Bulgaria, New Zealand, Luxembourg, Poland, Estonia, and Finland. And though coalition talks have not yet finished, things in the Netherlands seem to be headed in the same direction.

In addition to the aforementioned unpopular incumbents in Canada and the UK, Fumio Kishida’s approval rating is underwater (32-35), and Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats are currently polling in third place in Germany.

All of which is to say that while there is a bit of a global trend toward anti-immigrant parties, the dominant global trend seems more toward incumbents being unpopular and losing.

The Biden economic team likes to point out that inflation has been a global phenomenon, suggesting they don’t deserve to be held responsible for it. But not only is inflation happening everywhere, voters everywhere are (somewhat unfairly) blaming incumbents for it.

In particular, I don’t think anyone anywhere has pulled off what Biden wants to achieve — namely, getting voters to stop being mad about inflation just because the rate of inflation has fallen quite a bit. Discourse around this tends to ping-pong, with one person saying, “listen dummy, nobody cares that the rate of price increases has slowed what people want is for the price level to go back,” and then someone else saying “listen dummy, the only way to make the price level fall is a massive recession.” But what I think is actually going on is bitterness. If someone stomps on your foot and it hurts, you’re still going to be mad that it happened, even once your foot stops hurting. In Argentina, where the economy is genuinely in a state of meltdown, the electorate opted for a candidate promising radical economic policy change. But that’s not what’s happened in Italy or Australia or Sweden or Poland — people were mad about stuff that happened in the past.

Realities and vibes both matter

I bring this all up to support the boring conclusion that when it comes to people’s perceptions of the economy, both realities and “vibes” (the tone of media and social media coverage) matter.

Pure vibeologists cannot, I think, really explain why Joe Biden’s approval ratings are higher than his peers in Canada, France, the UK, Japan, and Germany. When you consider that Biden is facing some unique political headwinds related to his age and his wastrel son, he actually appears to be receiving significantly higher marks on the fundamentals than many other leaders. The best explanation for that, it seems to me, is that exactly as the White House’s allies like to say, the American economy really is doing better than any other major economy. If we were the UK, where the unemployment rate is higher and the inflation rate is also higher, Biden would be in much worse shape. Reality is a big deal, both because people experience real world economic conditions and also because reality influences how the media covers things.

That said, people do not have direct, unmediated access to all aspects of reality.

The National Federation of Independent Businesses, a lobby group for small business owners, does a monthly survey of small business owners’ sense of the economy. The most recent index shows that business owners in the aggregate plan to make capital investments, plan to hire new workers, have current job openings, and believe that right now is a good time to expand their business. But they also, by overwhelming margins, expect the national economy to get worse and national retail sales to decline.

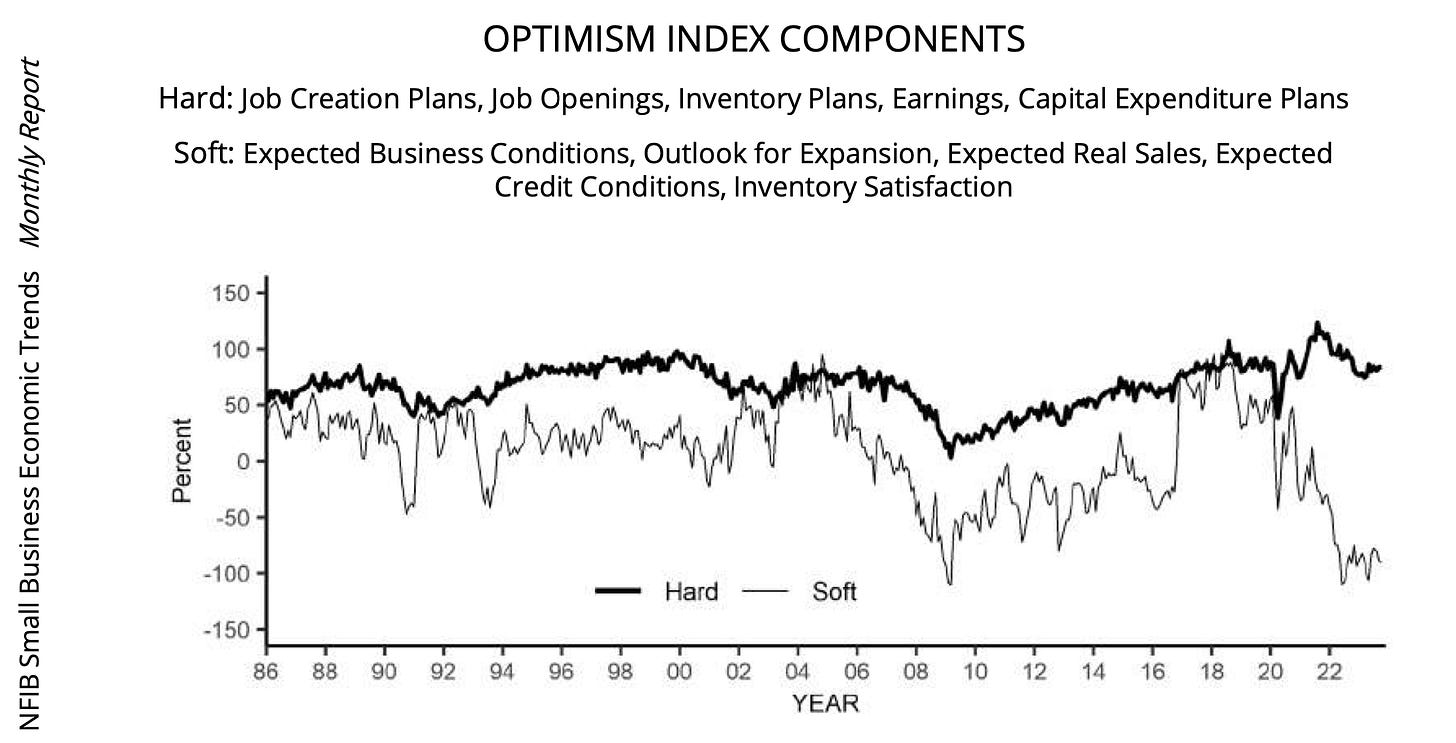

The NFIB conveniently produces a time series chart showing “hard” versus “soft” data, and you can see that the dominant force driving the gap is just that small business owners like Republican presidents.

This particular fact about small business owners doesn’t explain everything about economic perceptions, but I do think it’s an unusually clear illustrative example. It does also raise the question of why the hard/soft gap is larger for Biden than it was for Barack Obama, which probably relates in part to media dynamics, but also to Biden being less business-friendly. Obama invested a fair amount of energy during his first term in mostly-futile attempts to make the business community like him. Biden mostly hasn’t bothered, perhaps recognizing that Obama’s efforts were mostly futile. But “mostly” is not the same as “entirely,” and you do see a gap here.

What difference does it make?

Matt Bruenig and Jeff Stein have been on a quixotic campaign to try to convince people that negative economic perceptions are justified and do not simply reflect bitterness about past inflation, but are instead a direct result of hardships induced by the phaseout of Covid transfer programs from 2020 and 2021.

This would be a minor thing and easy to dismiss, but narratives that hit Democrats from the left tend to have disproportionate influence in the media, which likes to be non-partisan but is also full of very left-wing people. It’s also a little bit difficult to argue with them about this because Stein is a news reporter and Bruenig is Twitter’s best straight man, so neither of them will admit that this is really an argument about whether it’s politically constructive for progressives to make this argument. But I think it’s pretty clear that it is not. It’s not possible for Joe Biden to get an expanded welfare state enacted by a GOP-controlled House, and if Republicans win in 2024, they will (at a minimum) cut SNAP and Medicaid and most likely other programs as well. So if what you want to do is bolster the welfare state, what you should do is try to generate positive economic vibes.

In terms of actual policy options, though, I think this whole argument is a little pointless. The way I see it, either:

The Biden economy is on fire thanks to a strong labor market, so now we need to pivot away from a focus on job creation to a focus on increasing productivity and lowering costs.

The Biden economy is a disaster thanks to soaring inflation, so now we need to pivot away from a focus on job creation to a focus on increasing productivity and lowering costs.

The same is true, really, for the whole vibes versus reality debate.

To the extent that real economic problems are hampering Biden, he should try to pull out all the stops to reduce costs. And to the extent that his problems are vibes, then yes, his administration should encourage people to clap louder — but also, he needs to be seen as pulling out all the stops to reduce costs. Going in circles about whether wages have risen faster than prices (they have) and on exactly which time horizon doesn’t change the analysis. Now, if someone were to make the argument that actually, the labor market is really weak and it’s difficult to find employment, that would have large implications for policy. But as long as everyone more or less agrees that unemployment is low, it’s clear that the policy focus should be on inflation and interest rates, which is also clearly what the public wants. So there isn’t that much to disagree about.

Beyond the laundry list

This, I assume, is why the White House is putting so much communications emphasis on its efforts to lead a regulatory crackdown on “junk fees.”

That’s basically a good idea. My view is that the “greedflation” construct is a confusion, but what’s true is that when consumers are flush (whether from Covid stimulus or rising wages), companies try to get their money. Ideally, companies will get that money by expanding their real output. But many of them will also invest time and effort into rent extraction via confusion, and larding hidden fees onto everything is one way to do this. In a sense, the proliferation of special fees is actually a sign of economic strength — companies are not that worried about consumers being objectively unable to afford things. If the government is successful in cracking down on these fees, in part we’ll just see larger increases in formal prices because, again, consumers have money in their pockets and can buy things. But it will be more transparent, which will make markets function better and more competitively, and that will tend to lead to good outcomes.

That’s all great as far as it goes, but it’s also pretty superficial in terms of thinking about what’s really going on with the economy.

The basic picture is that we would like Americans to be able to buy more goods and services, and we want that in a world where we no longer have a huge pool of unemployed people who could be re-employed by providing those services. So we need policies that are geared toward increasing efficiency and productivity. That could mean taking on Dem-aligned interest groups by reforming Davis-Bacon or Jones Act rules. It could mean taking on GOP-aligned interest groups like car dealerships. Or, it could mean ideologically ambiguous options, like reducing land use regulations or freer trade or making it easier to site renewable energy projects and transmission lines. But it does, more or less, mean deregulation of some kind. Which means actually focusing on things that — unlike the junk fee crackdown — aren’t on the laundry list of progressive agenda items that you’d expect a Democratic administration to pursue in any macroeconomic circumstances.

My theory of the case for 2024 has been that Biden is a reasonable favorite so long as the current economic trends hold steady. 10 or so months from now of steady real income growth, relatively stable prices, and maybe a drop in interest rates, plus (God willing) the Israel-Gaza war being just about over for at least six or so months prior to the election should do a lot to stabilize Biden's position.

That, plus a re-orientation of the public with an every day in your face DJT should remind people why they hated him in the first place.

I have already noticed a shift in media coverage. Headline of the NYT today is another story about how radical Trump's second term can be, and I have seen more The Economy is Good, Actually stories lately, as well as the media explicitly calling out the gap between people's assessment of their own economic situation and their very negative assessment of the national economy.

All the above just takes time. This is simply the winter of Biden's discontent.

Please tell me why I am wrong

One implication of this is that Trump is an enormous albatross around the GOP's neck. Starmer and Poilievre are on track for landslide victories and Trump is tied with Biden. If Haley or some backbench senator was likely to be the Republican nominee, 2024 would not be close.