The media’s lab leak fiasco is the most-read Slow Boring post of all time.

The piece, which ran back in May 2021, reviewed some poor coverage decisions from February and March 2020 in which the media conflated a wild conspiracy theory (Covid-19 was caused by a Chinese bioweapon) with a plausible hypothesis (Covid-19 was caused by a lab accident), asserted that Tom Cotton was pushing the wild conspiracy theory, and proclaimed natural origins for Covid-19 with massive overconfidence.

I haven’t written about lab leak theory since because the boring truth is that we don’t know where Covid-19 came from, we probably aren’t going to find out, and very little of consequence actually hinges on the answer.

Of course, politically it’s a big deal. The case for stricter supervision of virus-related lab work would get a big boost if we could say with certainty that Covid-19 came from a lab. But I think the case for enhanced regulation is quite strong regardless of the specific origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. As, for that matter, is the case for stricter regulation (or permanent closure) of Asian live animal markets. These are the two most plausible sources of future pandemics, and we ought to be clamping down on both of them.

However, two new preprint papers (“The Huanan market was the epicenter of SARS-CoV-2 emergence” and “SARS-CoV-2 emergence very likely resulted from at least two zoonotic events”) with partially overlapping groups of authors are being widely touted in the press as definitively solving the debate in favor of natural origin.

Once again, I think the press is getting way ahead of its skis. These papers fill in some interesting details about the early outbreak at the market in Wuhan where the epidemic was first identified, but they don’t identify an intermediate host species that caught the virus from bats and then spread it to humans. Nor do they identify a precursor virus in a population of wild bats that lives near Wuhan or near farms supplying the Wuhan market. They show that the virus was introduced to the market at some point, but that could have been by humans who got the bug at a lab.

And so we’re left with the exact same dueling origin theories: it would be an odd coincidence for a lab-leaked virus to have its first big super-spreading event at a live animal market, but it would also be an odd coincidence for a devastating zoonotic coronavirus plague to occur in a city that happened to host a lab doing research on coronaviruses. It’s a genuinely weird situation. But we should keep in mind that the virologists publishing papers downplaying the possibility of a lab leak are not disinterested parties in this. The political context is a debate about regulating virus labs, and it’s hardly shocking that a large segment of the virus lab community doesn’t like that idea.

The state of play before the new preprints

The virus now known as SARS-CoV-2 first came to light due to a cluster of mysterious pneumonia cases in the city of Wuhan in China’s Hubei Province. Most of those early cases seemed to be associated with the South China Seafood Market, which also features live mammal vendors. That reasonably led to the initial presumption that the virus came from something at the market and the infamous mid-January tweet from the World Health Organization saying there was “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus.”

In other words, people might have been infected by an animal at the market.

Humans have not been operating virology labs for much of the course of history, so most new viruses have had zoonotic origins. And the particular idea that bat viruses could pass through an intermediate host and into humans was sufficiently well-entrenched that it is featured in the 2011 Stephen Soderberg movie “Contagion” (now streaming on HBO Max and highly recommended). In the movie, bats are disturbed from their natural habitat due to environmental degradation and take refuge on a pig farm. An infected pig passes the virus to a chef in Macau, who passes it on to a traveling American. So the idea that an animal picked up a bat coronavirus and then brought it to a live animal market in Wuhan where it passed to humans is a perfectly plausible interpretation of that early seafood market outbreak.

Over time, three basic issues emerged with this theory. No one has been able to identify:

A specific infected animal at the South China Seafood Market

An intermediate reservoir population in Hubei who were infected with a close relative of SARS-CoV-2 (pangolins were initially suspected but never confirmed)

A population of Hubei bats carrying a close relative of SARS-CoV-2

The closest relative of SARS-CoV-2 is Bat RaTG13. And while that fits the theory of a bat virus passing to humans via an intermediate host, Bat RaTG13 was identified in Mojiang in Yunnan Province, about 700 miles from the seafood market in Wuhan (roughly the distance between D.C. and Chicago, for those of us not familiar with the geography of southern China).

And that is the Covid-19 origin puzzle in a nutshell: how did a bat virus from a cave in Yunnan end up hundreds of miles away in Wuhan?

One possible answer is that Wuhan is home to a major lab, the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

In 2014, a team of Chinese scientists published a paper (“Novel Henipa-like Virus, Mojiang Paramyxovirus, in Rats, China, 2012”) that covers an incident in which “severe pneumonia without a known cause was diagnosed in 3 persons who had been working in an abandoned mine; all 3 patients died. Half a year later, we investigated the presence of novel zoonotic pathogens in natural hosts in this cave.” Later, a team from the Wuhan Institute of Virology went back to the cave in Mojiang and published the 2016 paper “Coexistence of multiple coronaviruses in several bat colonies in an abandoned mineshaft,” a study of a bunch of betacoronaviruses they found in bats in the mine.

It’s thanks to the hard work and diligent efforts of those WIV researchers that we know about Bat RaTG13. But this work also offers an explanation for how a bat virus could have traveled 700 miles from rural Yunnan to Wuhan: it was transported years ago by virus researchers.

So did the virus travel from Yunnan to Hubei a second time in an unrelated voyage, this time bound for the seafood market rather than the virus lab? Or did it travel from the lab to the market?

I don’t think the new papers shed much light on this at all.

What the new research shows

Carl Zimmer of the New York Times quotes Michael Worobey, one of the co-authors of both papers, as saying “when you look at all of the evidence together, it’s an extraordinarily clear picture that the pandemic started at the Huanan market.”

But I think it’s important to parse those words carefully. The evidence really does show pretty clearly that there were one or more superspreader events at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. I just don’t think that’s really what the lab leak debate is about; it’s about why there was a superspreader event at the market. Did an infected animal pass it to people there or did a person who got infected at the lab pass it to people there?

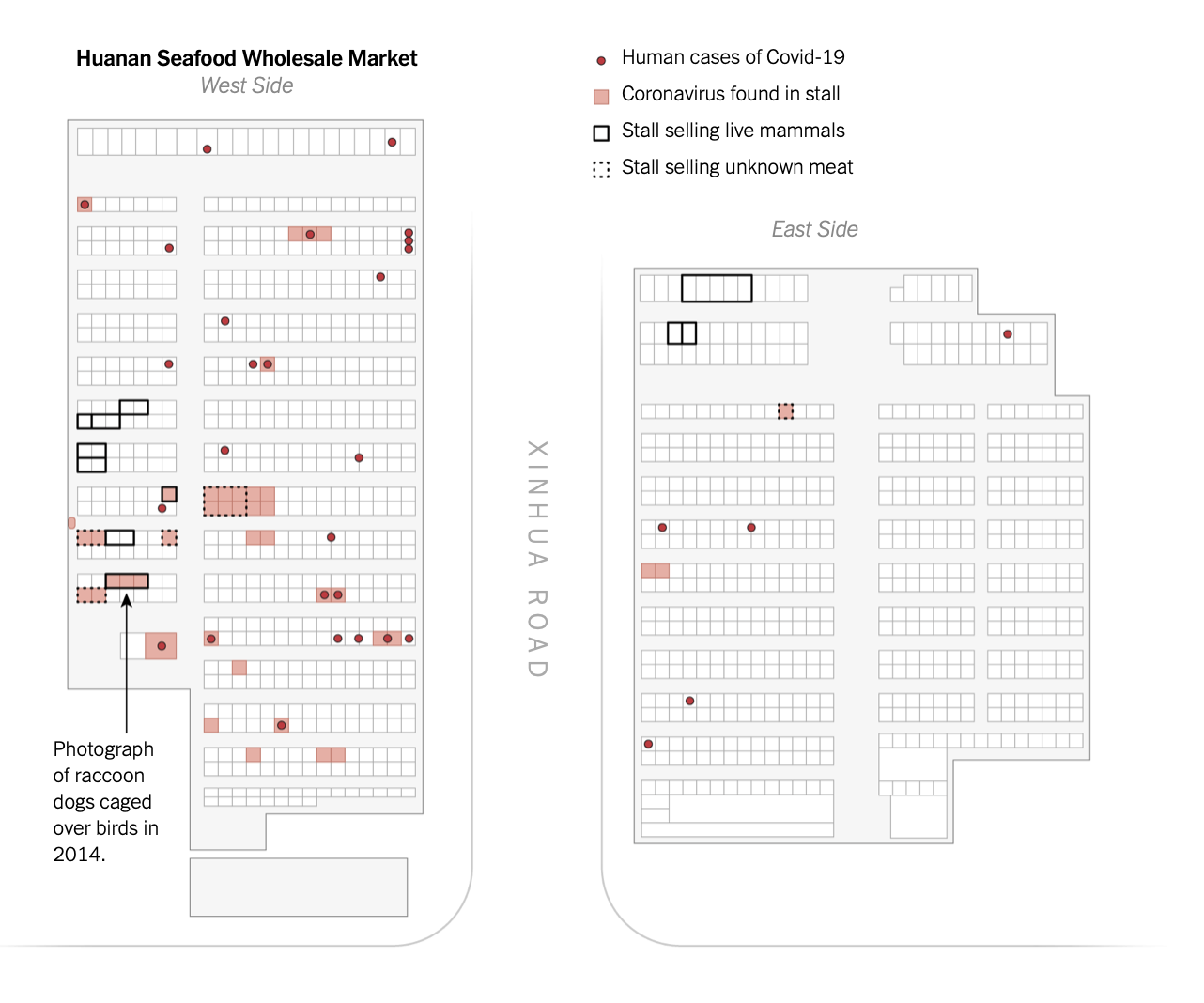

The new studies basically confirm what we already thought. The Times made this map based on the pre-print, and it shows that the virus seems to have spread to humans largely from an outbreak near the seafood market.

But I think we knew that — also note this is just the center of the city where the metro lines converge and lots of hospitals and other things are. Where they do move the ball forward is in nailing down where in the market the spreading seems to have happened.

But then things get a little weird. The map highlights one specific raccoon dog stall. The human cases are not particularly clustered near this stall, but the virus samples found on surfaces in stalls are. The Times made a heat map that ignores the human cases and just plots the stall samples (I’m not totally sure why would you do that?), and then the finger points really squarely at a specific stall that sold live animals.

All of this evidence is clearly consistent with the zoonotic origin theory. A raccoon dog got the virus from a bat, was brought to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, and the virus then spread to humans.

But you could also draw a map focused on the human cases that would have shown a cluster in the other corner. And certainly the evidence is all consistent with the theory that a human got the virus at the lab, brought it to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, and triggered a super-spreading event at the market (potentially infecting raccoon dogs along with humans).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.