As we often do on Federal holidays, we’re unlocking an older paid post (today’s is from December 2021) that many of our current subscribers haven’t yet had a chance to read. We’ll be back with a fresh mailbag tomorrow. In the meantime, have a great 4th of July!

Like a lot of people who write about politics, I’ve been interested in history for a long time.

That’s mostly meant the history of relatively recent events in the west — things like Eric Foner’s book on the ideology of the early Republican Party or nationalism and revolution in the 19th century Habsburg Empire. But more recently I’ve been getting interested in some topics in the distant past like the origins of the Indo-European languages, the origin of states, and ancient DNA research into prehistory.

These are interesting topics in their own right. But they also cast more recent history in a different perspective, especially the history of economics and living standards. Or I guess, to put it another way, thinking about the distant past underscores that recorded history proper is a relatively small portion of the total story of humans, and the modern era of technological dynamism and rising living standards is itself a small portion of recorded history.

And when you start to see it that way (or at least when I do), your level of certainly about the meaning of relatively recent, relatively small-scale trends starts to go down. We mostly take for granted a tendency toward steady progress and rising living standards that is, in reality, not at all a constant feature of the human story.

Of course technological progress is something that’s been happening this whole time. Indeed, human technology long predates our species Homo sapiens, with the Oldowan stone tool technology invented by Homo habilis and later inherited by Homo erectus. Erectus eventually advanced to the Acheulian stone technology, but the move from Oldowan technology to Acheulian took about a million years.

What’s so striking about Oldowan technology’s million-year run is not just that it’s a long time — it’s that this is longer than Homo sapiens have been on the planet (roughly 300,000 years). And Acheulian technology, again, lasts longer than the entire duration of our species. Homo sapiens is just incredibly new, not just relative to geological time or the history of the universe, but relative to the basic practice of upright-walking, tool-using apes roaming the earth in hunter-gatherer bands.

We’re evidently much better at inventing stuff than our Homo predecessors were because in our time on Earth, we’ve done a lot better than one or two upgrades of our basic stone tools. But even within the sapiens era, there is an incredible telescoping of technological progress.

For most of time, not much happened

Our species is about 300,000 years old, and farming and towns started about 12,000 years ago. The vast majority of the history of human technology unfolded before the existence of our species, and the vast majority of our species’ existence was prior to permanent settlements.

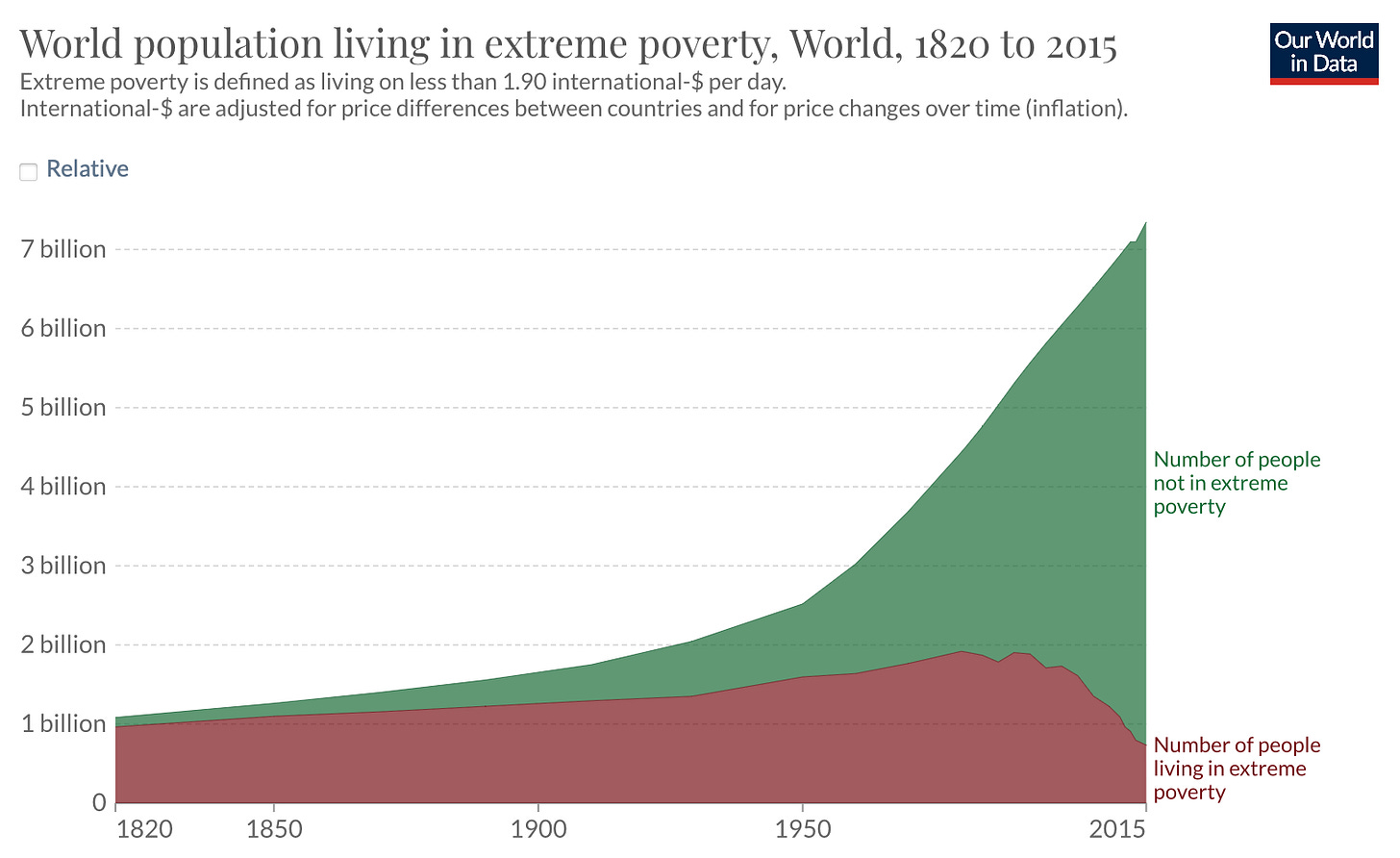

And per this Luke Muehlhauser chart, it was really only starting 200 or 300 years ago that we see any kind of sustained upward momentum in living standards.

It’s not really that living standards never changed before the industrial revolution. For the sake of legibility, Muelhauser’s chart covers about 3,000 years rather than 300,000.

If you did go all the way back, you’d find that the neolithic revolution — when people turned to agriculture — was also a big deal. The problem is that, as Jared Diamond and now many other scholars seem to agree, agriculture made living standards lower rather than higher. Or if you want to be fussy about it, you can agree with James Scott that the problem was not agriculture per se but grain.

What’s nuts to me, though, is that this whole agricultural era is just so damn short in the context of human history. Holden Karnofsky made a nice chart of life getting worse and then better, but to make it look nice he puts aggregate lives lived to date on the x-axis rather than something more conventional like time.

It’s a fun move and certainly a much nicer chart than if you’d tried to do it to scale by time. That said, I think the extreme paucity of meaningful technical progress during the majority of human history is an important piece of context. As is the fact that one of our key breakthroughs took us backward.

The pernicious logic of agriculture

The world of anti-farming takes has gotten mixed up with paleo bros and weird crank diets, so it’s worth stepping back to take a broader view of things.

In neoclassical economics, we have two factors of production — capital goods and labor. The original classical economists were wiser and had a third factor — land. Hunter-gatherers didn’t have a lot of capital, so for them, land and labor were the key factors. If you were someplace where there’s fruit, you could get yourself some fruit by deploying a little gathering labor. Similarly, if there’s meat, you could get some meat by deploying some hunting labor.

But because you get the non-metaphorical low-hanging fruit first, your gathering labor has sharply diminishing marginal returns. If you hunt, you kill some animals and scare the others off. The land itself is just not very productive, which is why you’re living in nomadic bands. But the non-productivity of the land also means that you only need to work so hard because there’s really no point in putting in more hours. For analog-era journalists, the number of column-inches of copy the editors would print was constrained by the number of ads that were sold — there just wasn’t that much demand for content. On the internet, there’s no objective limit on the number of articles you can afford to run, so there is a lot of pressure to publish at high volume. Nomads work hard — up to a point — but then they stop.

The point of farming is that you can generate radically more calories per acre than by roaming through the wilderness.

But in general, this just results from the factors being complementary — you can make the land much more productive by working really hard. I don’t think this is true on a strictly uniform basis. I once met a family that owns an olive farm, and they described it as a pretty chill situation outside of peak harvest time. But even though olives are delicious, an olive grove is not generating a lot of calories per acre. A rice paddy, by contrast, has incredibly productive land. Today we’re not limited by our local farming capacity, but the long arm of the past is still with us, and population density is incredibly high where the highly productive rice agriculture was.

But there are two problems. One is you need to work insanely hard to maximize the productivity of that field.

The other is precisely in that population density. If some new farmland opens up, you probably start out on easy street — plenty of places for some orchards, pastureland where the animals can just chill until you kill them, plus a little agriculture. You’re doing great, and you’re having more surviving children than your hunter-gatherer ancestors. But that just means the population grows, so you need to replace the orchards with more productive land use that also requires more work. And then you’re scaling back the pasture too, because a field of wheat can produce a lot more calories if it’s directly consumed by humans than if it’s a field of grass that’s consumed by cows who are in turn consumed by humans. But now you’re working crazy hard and eating worse food than a hunter-gatherer.

The good news is that by having a settled lifestyle, you can accumulate possessions. The bad news is all your stuff can be stolen.

The road to serfdom

This is Scott’s point about grain specifically: because it’s harvested at a specific time and then dried and stored, it’s ideal for stealing. You could show up at somebody’s radish field and dig up their radishes, but then you’re actually doing some of the work of running a radish farm.

But you can cart off a ton of rice or barley or millet or corn and make a nice living as a bandit. Or you could become one of Mancur Olson’s “stationary bandits” who decides to start calling the stealing “taxes.” Or maybe the village organizes a squad of trained and equipped fighters to stop bandits from stealing your stuff, but then it turns out you’re paying protection money to the fighter class. Either way, in addition to people working harder than before, there’s this new class of people who don’t grow the food and just take stuff.

To the extent that there’s a virtue to the agricultural revolution, this is it:

By making the land much more productive, you allow the aggregate size of the human population to become much larger.

By turning most people into sedentary sitting ducks, you allow the creation of a surplus-extracting exploiter class who are much richer than the richest hunter-gatherer.

When I first read Derek Parfit’s “Reasons and Persons,” I viewed the “repugnant conclusion” thought-experiment about shifting society to one with a much larger population at considerably lower standards of living to be interesting but also a kind of weird hypothetical. But one of the signature developments of our history really did have that character — pushing the median living standard down considerably but raising the number of people dramatically.

But the exploiter class is really important to the legacy of this period. When you first hear the idea that agriculturalists had lower living standards than hunter-gatherers, it seems absurd. You think about Classical Greece, Ancient Rome, the Umayyad Caliphate, Henry VIII, and everyone who comes to mind seems to be living a lot higher on the hog than a hunter-gatherer. In dramatic renderings of Medieval or quasi-Medieval settings, whether we’re talking “Game of Thrones” or the recent “The Last Duel” (which is really good and I wish more people had seen; check it out when it comes to streaming), the focus is almost always on members of the elite minority. They’ll show you class conflict between relatively more- and relatively less-elite members of the elite, but there’s little dwelling on the large majority of the population who were serfs or peasants of some kind.

The industrial era

Experts disagree somewhat as to when to date the start of the takeoff, but even though we had steady technological improvements during the agricultural era, it’s not until the mid-18th century (at best) that we see sustained improvements in living standards. Before that, whether we’re talking about inventing ironworking or windmills or whatever else, progress is real. But, it is slow enough that population growth catches up and median living standards collapse back to their sub-hunter-gatherer level. All the gains accrue to the extractive, exploitative elites who are able to confiscate more surplus as the bulk of the population is pushed back to subsistence levels.

The sustained increase in agricultural yields and industrial productivity of the past 250 years hasn’t been like that.

The typical English person in 2021 has higher living standards than the typical English person of 1921, who in turn was better off than the typical English person of 1821, who was probably better off than the typical English person of 1721 (though this last one is a little less clear). The 2021 > 1921 fact is even true for the typical resident of the world. But note that on a global scale, there’s no real sign of sustained progress until the second half of the twentieth century.

The dark portrait that Marx and Engels painted of the industrial revolution as immiserating the working class was completely wrong. But it’s easier to understand why you might have made that call given all prior technological improvements had, at best, led to the growth and enrichment of an extractive elite. There’s even an account from Robert Allen holding that British working-class wages didn’t start rising until around 1840, so the immiseration story was even true as a direct observation of the early industrial revolution.

But stepping back, it turns out that the industrial revolution in the North Atlantic world and then the spread of prosperity due to decolonization and globalization after 1960 or so are basically the best things that ever happened.

What does this all mean?

My main takeaway from looking at the really big picture is that we should be less certain about a few things.

I used to be totally dismissive of the idea that automation could lead to bad economic outcomes because my view was people “always” had this fear about new technological developments, and it was “always” wrong. But it wasn’t actually always wrong. The Neolithic Revolution set average living standards on a downward trajectory for a few thousand years, and they stayed at a low level for a long time. Is it likely that we happen to be living on the precipice of an event like that? Probably not, but it’s not impossible. You shouldn’t make categorical statements about human history based on observations from a 150-year period.

Some other thoughts:

It’s easy to understand why people have a lot of deeply entrenched, albeit wrong, Malthusian intuitions because that’s how life was forever and ever.

The social media experiment in “connecting people” is in some ways weirder and more contrary to history than I think we sometimes appreciate; until very recently, almost everyone was living in small towns.

It’s commonplace to refer to the slower productivity growth since 1970 as a “stagnation” relative to the 1870-1970 pace, but the 1970-2020 period still features more per capita growth in a 50-year span than was typical in human history. Much more growth. So what’s really the anomaly here?

The whole idea of trying to invent new ways of doing things seems to be perhaps more novel than you’d think. People were flaking stones the same old, same old way for unimaginably long spans of time.

Human history is kind of bleak. There’s a lot of talk these days about the “dark parts of our country’s history” and how to think about them. But I’m not really sure we’ve had a conversation about the generally dark trajectory of all this history in general, which seems broadly lacking in uplifting themes about progress until suddenly it’s not.

It’s also really hard to tell what’s going on while you’re living through it. Marx, as we saw, grasped the world-historical significance of the Industrial Revolution but also called it totally wrong. It’s sort of conventional to counterpoise him to Adam Smith as the advocate of market capitalism, but if you read Smith, he’s remarkably uninterested in technological progress and actually isn’t cheerleading for the Industrial Revolution that’s beginning to unfold around him. What Smith is saying is that a market economy leads to a more efficient allocation of a quasi-fixed pool of resources, which is true but also not what led to the explosion of prosperity over the next 250 years.

Mostly, though, my upshot from all of this is to be more attendant to downside risks.

There is a sense in which our modern, prosperous technological era represents the steady accretion of knowledge over a long period of time as part of an upward ascent of humankind. But there is also a pretty profound sense in which this is not true. The hundreds of thousands of years of human bands wandering the earth and not changing very much dramatically outlast the story of human progress. Then for the majority of recorded history, most people were living worse than the paleolithic hunter-gatherers. If everything collapsed tomorrow and we entered a 50,000-year span of global impoverishment, that wouldn’t necessarily be outside the observed norm. But it’s also conceivable that today’s human children will be the creators of a cohort of self-replicating and self-improving AI robots that colonize the galaxy.

Which will happen? I don’t know. Which is more likely? I don’t know. What I do think I’ve learned from the truly longue durée is just how live all the different possibilities are. A lot of the things we “know” — a steady pace of technological progress that is rapid enough to generate consistently rising living standards — actually comes from a surprisingly small and local sample of the broad sweep of human existence.

Yuval Noah Harari's book Sapiens argues that it is perhaps more accurate not think of humanity domesticating grain but grain domesticating humanity! Human life was radically altered for the benefit of the grain reproductive cycle.

I'm also currently reading the book about the origins of Indo-European languages. My fellow nerd, I salute you.