How Wuthering Heights keeps changing

Movie adaptations and shifting racial politics alter the meaning of Emily Brontë’s classic novel

As part of my ongoing quest to unscramble my brain by reading classic literature, I recently wrapped up an eight-week Zoom discussion group on Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel “Wuthering Heights” run by The Catherine Project.

This was, to put it mildly, not my favorite of the various 19th-century English novels I’ve read this year. But because I actually discussed it at length with other human beings, I did end up engaging more deeply with the text than some of the other books I enjoyed more. We also read the book at a slower pace than I normally read, so I had plenty of time to process my reactions and poke around on the internet to get a sense of others’ and learn about the many film adaptations of the story.

Still, I ultimately found the novel a bit unsatisfying. Brontë writes some great scenes, but with the complicated multi-layered framing device, I often found it hard to know what to make of the plot and I missed the social realism that a lot of other celebrated works of this time have.

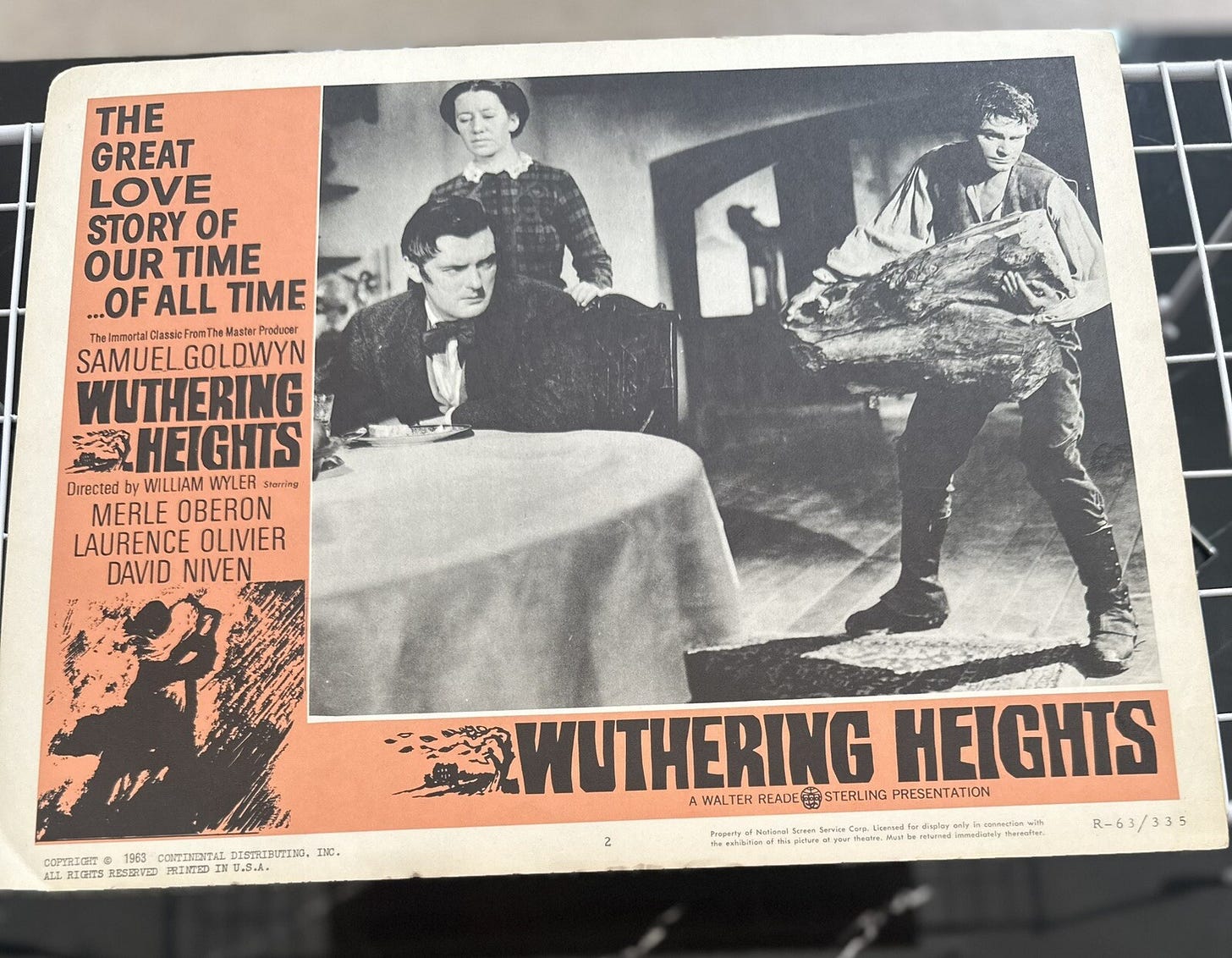

But some of these unsatisfying elements are what make it an interesting text to engage with — the book has been received differently in different eras, in response to different modes of criticism and evolving political sentiments and social norms. I also think, though, that interpretations of the text have been driven at least in part by the film adaptations, many of which wrestle Brontë’s story into something more straightforward than the book: a great love story, as the distributors of the 1939 version put it.

The love story between Catherine and Heathcliff that is the focus of this adaptation — and most subsequent ones — is the real cultural legacy of the book. It’s the thing people who half-remember “Wuthering Heights” from high school remember, it’s the thing people who haven’t read it think they know about it, and it’s the thing that ends up on movie posters. But (spoilers) Catherine dies in Chapter 16 of a book with 34 chapters, and the first three chapters are spent setting up a framing device in which she doesn’t appear. The relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff is a crucial driver of the plot, but in a literal sense, the book mostly consists of other stuff.

On a straightforward reading of the text, Heathcliff is more like an antihero than the kind of character you’d expect to see played by dashing leading men like Laurence Olivier, Charlton Heston, Richard Burton, Timothy Dalton, Ralph Fiennes, and Tom Hardy.

Hollywood went spelunking in a novel about multi-generational child abuse, abduction, and betrayal, and pulled out something more film-able. And yet, there are modern readings of the text that suggesting maybe the Hollywood version of the story is something closer to the “right” one, and that the story told the novel is a kind of slander perpetrated by a small-minded racist.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.