How IRA results are stacking up to predictions

Our first reader's choice Friday column, on...

Welcome to the first edition of our new Friday column! This week is free for all readers, but going forward it’ll be for paid subscribers.

Thank you to everyone who submitted a question or an idea; we really liked all three of our finalists and were happy to see some new voices join in the mailbag thread. This week’s winner was, I thought, particularly interesting, and I went a bit longer than we intended this column to be (and it might be a little shorter going forward).

But first, some good news and things we enjoyed reading this week, including some reader comments!

Sacramento did away with exclusionary zoning, a new frostbite treatment may help people avoid amputation, and evidence suggests that even building luxury housing helps put downward pressure on all rents. Pandas are coming back, and the Biden administration is making a real effort to combat money laundering.

We also loved hearing from Slow Boring reader Miyero about their success advocating for better bus service in their hometown! And Laura added helpful context, as a Cambridge public school parent, to our piece on tracking in schools.

Another new thing we want to add to the Friday columns is some recommended reading:

Michael Grunwald on Ron DeSantis vs lab grown meat.

I’m intrigued by Ruxandra Teslo’s thoughts on Gen Z gender norms.

Kriston Capps on the death by everything bagel of a federal office-to-residential conversion program.

Mike: The IRA seems to be struggling to have the effects that experts predicted based on a bunch of computer models. This seems reminiscent of the way that the ACA failed to change the healthcare system in the way that experts predicted based on their models. Is there a way to make policy that's more robust to failures of prediction, or is this just the best we can do in an uncertain world?

They say that predictions are hard, especially about the future.

But I would say, generally speaking, that if anything, we under rely on quantitative forecasts when thinking about and debating policy.

One reason I’m so annoyed by climate activists’ push to curtail LNG exports is that they haven’t done any formal modeling, at all, of the net emissions impact of the policy in which they’re advocating. Formal modeling wouldn’t settle the debate, and any given forecast isn’t even particularly likely to be correct. But a formal model would reveal the assumptions these advocates are relying upon. To the extent that activists have thought this through at all, they are relying on out-of-consensus work by Robert Howarth that says LNG is actually dirtier than coal. Precisely because they’re relying on that assumption, they’re not asking a question that’s of interest to most of us who are concerned about this issue: How much does reducing LNG availability boost coal relative to boosting renewables?

It seems to me that most mainstream media coverage of the debate on this hasn’t made the stakes of this technical issue clear.

They treat it as a struggle between Joe Biden’s national security team (which likes the idea of customers buying American rather than Russian or Qatari gas) and political advisors who are networked with climate groups and who want to accomplish everything they can to reduce emissions. And that is, in fact, a real struggle. But the assumption that reducing American exports will reduce emissions is questionable — lots of scientists think Howarth is simply wrong.

I would love to see more people really laying out the work that leads them to different views on the overall policy question.

If the US curtails LNG exports, how much does that change global consumption of gas vs shifting production to other sources of natural gas?

If natural gas consumption goes down, how much does coal consumption go up?

What is the relative emissions impact of coal vs gas?

Even if we don’t have consensus on those questions, it would be good to map out the space of possibilities to really see what we’re arguing about. But all too often, we don’t actually do that. One of the nice things about IRA modeling, though, is that people really did do the work, so we can ask questions about what the models say.

Why the IRA is falling short (so far)

In terms of IRA itself, the Rhodium Group (a major climate modeler) did a good update recently explaining where things stand.

They say that zero-emission vehicles sales are actually pacing somewhat faster than they had forecast. This is going to be surprising to some people, because there have been a lot of headlines about disappointing EV sales this year, but those headlines are generally talking about the “Big Three” US automakers being disappointed by sales of their EVs. That’s a big and important business story, and a big story potentially about the political sustainability of the Democratic Party’s push for EVs. But Tesla is selling a lot of cars, and Hyundai and Kia are seeing strong EV sales growth in the American market. Globally speaking, Chinese companies, led by BYD, are doing great with electric cars. So EVs are doing fine, as climate policy. To the extent that there’s an issue here, it’s maybe an issue with the industrial policy aspect.

But also maybe not — Tesla is a great American success story, even if Elon Musk is an asshole on Twitter.

The problem, per Rhodium, is that zero-emissions electricity hasn’t been growing enough to keep pace with IRAs goals.

Why is that? Well, as Rhodium explains, the problem is that even though the IRA provides large financial incentives to deploy zero-emissions electricity, there are tons of non-price barriers to actually deploying it:

On the other hand, even though investment in utility-scale clean electricity generation and storage capacity reached record levels in 2023, it is at risk of falling behind post-IRA projections. The IRA has made renewable electricity cost-competitive with coal and natural gas (short-term cost inflation in 2022/2023 and a lag in issuing guidance on some tax credit provisions notwithstanding). The biggest barriers to deployment between now and 2030 are non-cost in nature—like siting and permitting delays, backlogged grid interconnect queues, and supply chain challenges. Tackling these non-cost barriers will be critical for the IRA to achieve its full clean energy deployment and emissions reduction potential.

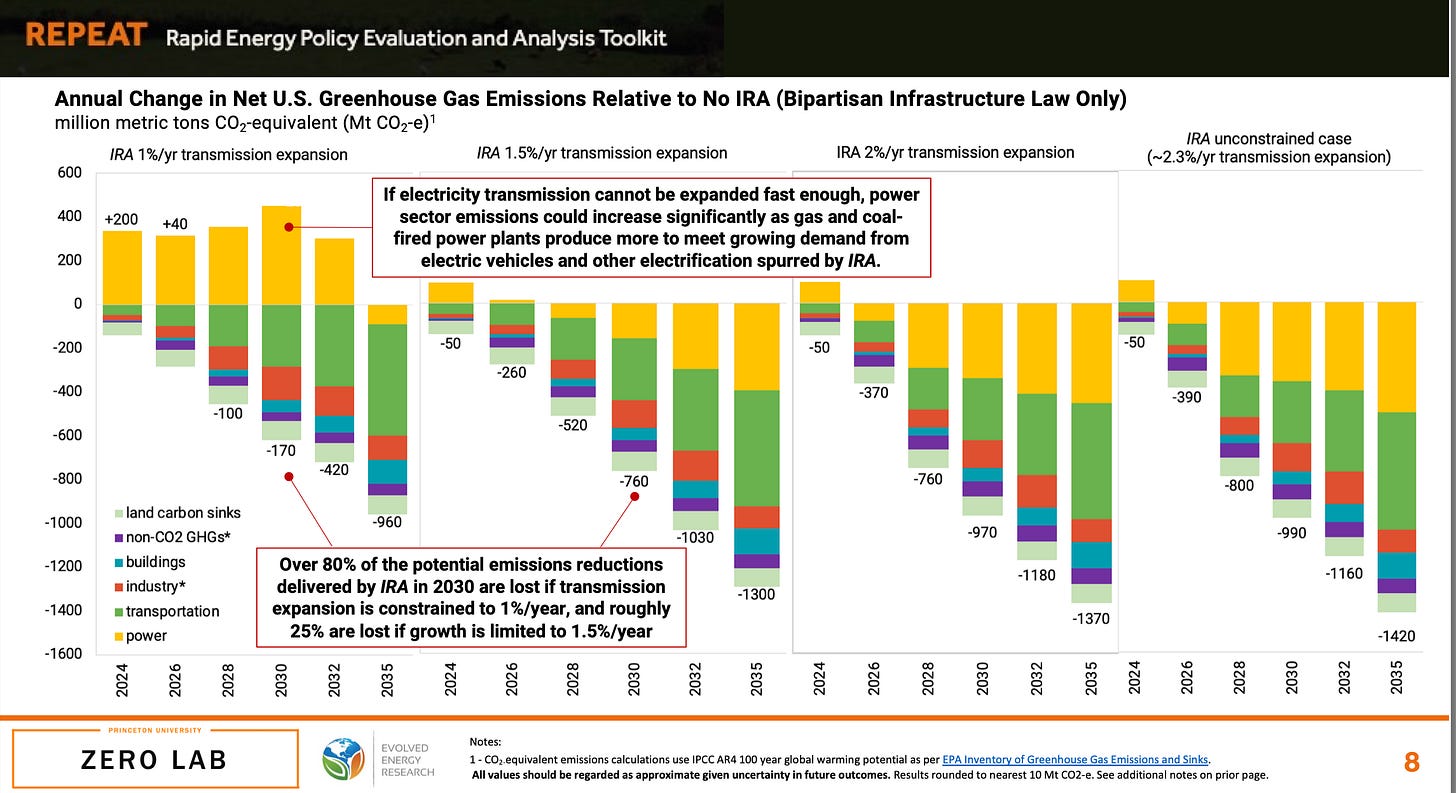

Ooops! How did the modelers miss this? Well, it turns out they didn’t miss it. If you look at the REPEAT Project’s models, for example, they do, in fact, say that this is all contingent on a gigantic expansion in transmission capacity.

This, again, is why it’s useful to actually do the modeling, even if the forecasts are never going to be exactly correct. The act of sitting down and deploying numbers reveals questions like, “if renewables production were to accelerate, what would need to happen with electricity transmission?” And it turns out that a lot would need to happen, and that the IRA itself doesn’t contain anything to make it happen. But this then gets you into a question of communication. On some level it’s not true that the IRA has underperformed relative to model-based expectations. The models, after all, said we would need to address these non-cost barriers, and we didn’t address them. But at the time, the models were not really pitched that way. They were pitched as revealing that the IRA would have a really large impact, not that the IRA would have a large impact if and only if other complementary legislation passed.

Politics is hard

Here you wind up getting into some inherently uncertain territory.

Thanks to the wisdom of senate procedure, it is possible to create a lot of subsidies for clean energy in a budget reconciliation bill, but it is not possible to rework permitting for electricity transmission projects or renewables siting. Thus, if you want to write a reconciliation-eligible climate bill, which Democrats certainly did, you basically have to do it the way they did it — spend the money in one bill, and then negotiate a bipartisan deal to address the non-cost issues on a separate track.

More than bad modeling, what I think you can accuse the IRA forecasters of doing is hiding the ball somewhat in the framing of their analysis.

“This legislation WILL NOT GENERATE STEEP DECARBONIZATION unless you make COMPLEMENTARY POLICY CHANGES TO ADDRESS TRANSMISSION” and “this legislation WILL GENERATE STEEP DECARBONIZATION as long as you also make complementary policy changes to address transmission” have the exact same truth conditions. But they deliver different messages to the public and to congress. There was a critical moment at which delivering a positive framing about the benefits of the IRA was important to getting progressives on board with a compromise heavily shaped by Joe Manchin, and I don’t have a problem with people running with an effective political message. And there’s a reason that both Manchin and the White House immediately turned around to work on permitting legislation. The key actors did get what was going on.

That said, I am not sure that backbench safe seat Democrats or the environmental advocacy groups whose approval they crave get this.

The actual thing the advocacy community has pivoted to is a renewed focus on pipeline fights and this new battle over LNG exports. They need to understand, though, that the IRA really has put zero-carbon electricity on a path to outcompete fossil fuels if and only if complementary regulatory changes are made. Those can be changes on transmission, changes on geothermal, changes on nuclear, or ideally all three. But we do have to make changes — changes that can’t pass the senate on a reconciliation vote, changes that need to take into the account the needs of Democrats from energy producing states like Pennsylvania and Colorado, and, very likely, changes that require buy-in from House Republicans as well.

The good news is that unlike the idea of “spending a ton of money on subsidizing low-carbon energy,” the idea of “engaging in targeted deregulation to help low-carbon energy” is an idea that Republicans don’t necessarily hate. At the same time, it’s not an idea they love. To get them on board for a bill, Democrats will need to make concessions. And for that to happen, they need to understand how much the IRA’s success hinges on these additional changes.

Accurate analysis is underrated

The ACA modeling situation is also an interesting one to think about in this regard.

Early forecasts got three things wrong that, in retrospect, were mistaken evaluations of the political situation rather than mistaken analysis of the policy situation:

The Supreme Court made it much easier for states to opt out of Medicaid expansion than the bill’s authors had intended.

Most GOP politicians were much more eager to opt out of Medicaid expansion than a rational fiscal calculus would suggest — the two very large states of Texas and Florida are still holding out.

When the Obama administration sat down to write detailed rules to enforce the individual mandate, they consistently opted for politically cautious weak choices that left the mandate very ineffective.

The first two are just tough; the third is really weird. After all, nobody made the Obama administration impose a politically controversial individual mandate. Obama himself ran against the individual mandate in the 2008 primary, specifically because it was too politically contentious. Then he talked himself into the idea that it was necessary to bite the bullet to make the ACA work. But then when it came time to implement, he talked himself back into the idea that it was too politically contentious to be worth doing in a really tough way. That’s why when the mandate got repealed under Trump, it didn’t have much effect — the mandate was never really implemented in the first place. The ultimate conclusion Obama reached about this was perfectly reasonable, but since he both started and ended with the conclusion that the risks of a tough mandate were too big, it didn’t make a lot of sense to spend years being on the unpopular side of this issue in congress and in the courts.

On the other hand, another major aim of the Affordable Care Act was to “bend the curve” and to slow the growth of health care service unit costs. On this side, the curve bent more than expected. People argue about how much of that is thanks to the ACA versus just errors in estimating the pre-ACA baseline. But I think there’s a good case that the ACA deserves credit. Either way, the upshot is that the law has cost a lot less money than was originally forecast.

That’s important because two major political constraints on the original bill were that it had to reduce the budget deficit and it had to have a headline cost of under $1 trillion.

If the forecasters had been more accurate, they would have known they actually had more room to play with on both of those parameters and could have made the subsidies more generous. This all loops back to something I wrote back in April of 2022, which is that while there’s a place in life for political propaganda and messaging, I think both coalitions actually underinvest in substantive policy analysis. A lot of people seem to assume that these complicated technical questions — “how much good will an individual mandate accomplish if it’s implemented in a relatively weak way?” — are unimportant or that the answers are so obvious that all that matters is muscling your preferences through. But as soon as you start to think about any policy question at any level of detail, you’ll see really quickly that these questions are hard and that what you want to do politically hinges, at least in part, on the answers.

Does anyone else always read IRA as Irish republican army?

Not detracting from this article - but the reader mailbag was my favourite feature of the week, and I am quite sad to see it go!