How I learned to stop worrying and love the Washington/Baltimore/Arlington Combined Statistical Area

And how to make it work as one city

Cities are fundamental to understanding the geography of human life.

But the “city” as a set of political lines on a map has a tenuous relationship with the city as a set of economic and social relationships. My mom grew up in F

lushing in Queens and would tell stories about going “into the city” (by which she meant Manhattan) from her house. I have friends in the Alamo Heights exclave who describe themselves as living in San Antonio. And certainly, when my dad was living for a few months in Santa Monica and I visited him, I told people I was going to Los Angeles.

We often talk about a metropolitan area (a city and its suburbs) as a unit. Many more people live in the City of Austin than in the City of Atlanta, but Atlanta feels like a much larger city — more pro sports teams, much bigger airport, more corporate HQs — because the Atlanta metropolitan area is dramatically larger than the Austin metropolitan area. By the same token, Jacksonville is only a bigger city than D.C. in the very technical sense that the municipality was merged with Duvall County, so its boundaries are extremely expansive.

In the United States, metro areas are defined by the Office of Management and Budget, which looks at commuting flows between counties and then groups them together into larger areas.

They compute this in a few different ways. There’s the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), the Micropolitan Statistical Area (μSA), and the Combined Statistical Area (CSA). A μSA is basically a one-county metro area — a small city and its surrounding area — while MSAs and CSAs are big cities and their suburbs, with the MSA definition being narrower and the CSA more expansive. In some cases, narrow versus wide is pretty straightforward. My in-laws live in Kerr County, Texas in the Kerrville Micropolitan Statistical Area adjacent to the San Antonio MSA. The San Antonio CSA expands to include Kerr County. And I think that describes the area well — it’s not quite a suburb of San Antonio (when you drive on I-10 past Boerne there’s a distinct gap in development until you hit Comfort, which is very small, and then another one between Comfort and Kerrville), but it’s close. With another decade or two of Texas-sized population growth, it probably will be.

But in other cases, the move from MSA to CSA involves combining two distinct metro areas, which brings us to today’s topic: the Washington MSA and the Baltimore MSA combine to form a single Combined Statistical Area. I used to hate this idea, but I’ve come to accept it. And I think all residents of Balt-Wash should come together to think about how we can make a cohesive metro area work better.

The case for CSAs

Here in the northeast, we are clannish and parochial. If you go from D.C. to New York, you pass through several distinct dialect zones and sports fandoms. Providence has a different set of organized crime than Boston.

You go from hoagie to hero to grinder.

And in that context, to say that D.C. and Baltimore are the same city is absurd. In D.C. we have a popular football team. There is also a robust local tradition of anti-fandom grounded in the franchise’s historic racism, which induces a minority of Washingtonians to root for the local team’s longtime rivals the Dallas Cowboys. But there are no Ravens fans. Or, rather, my one friend who grew up in Baltimore is a Ravens fan, just like people who move here from Boston root for the Patriots. When the Nationals came to town it was a big deal because previously, D.C. did not have a baseball team. We didn’t have the Orioles, because we are not a suburb of Baltimore.

But I did see a truck in my neighborhood recently that was repping the Os and the Capitals. And if residents of Charm City and its suburbs are willing to open their hearts to D.C.’s hockey team, maybe they’d love the Wizards, too, if the Wizards weren’t terrible. Maybe we could all just be one big city?

The CSA makes more sociological sense on the west coast.

If you go by MSAs, the 13th largest city in the country is Riverside, California. Riverside, according to the stats, is bigger than major cities like Detroit, Seattle, Minneapolis, or Denver. But what the fuck is Riverside, California? They don’t have a distinctive regional accent or cuisine. They don’t have any pro sports teams.

The answer, if you look on a map, is that the “Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario Metropolitan Statistical Area” is just an extension of the general sprawl around Los Angeles. People there will make wildly overstated claims about Kobe Bryant, and if they want to go to Paris or Tokyo they get a direct flight from LAX. And indeed, the OMB’s CSA version of Los Angeles includes Riverside.

If you go by MSAs further north in the state, then San Francisco and Oakland are part of a single metro area, but San Jose is a separate metro area that includes Palo Alto and Mountain View but not Menlo Park, which is in San Mateo county and therefore part of the San Francisco MSA. The 49ers not only play outside of the City of San Francisco (which is typical for an NFL team), they’re not even in the San Francisco metro area, which seems nuts.

If you go by the CSA definition instead, it’s all one big metro (“the Bay Area”) with multiple activity nodes. And that makes a lot more sense. So I’m ready to let go of my northeastern parochialism and embrace it, in part because of lifestyle changes induced by Covid-19.

The pandemic changes things

One thing that happened during the pandemic is that for a while, all my kid’s usual weekend activities were canceled. So for the sake of getting out of the house and engaging in some virus-safe outdoor activities, we started going on Saturday hikes.

I’m not an outdoorsy person by nature. And the D.C. area isn’t one of these places like Denver or Portland where people are always talking about how there are all these great hikes nearby. So until forced by circumstances, I never really made an effort to explore the region’s offerings, even though I’ve lived here a long time. But thanks to the virus, I started visiting lots of places for our father-son outings, and many of them — Calvert Cliffs State Park in Maryland, Sky Meadow State Park in Virginia, the battlefields at Chancellorsville and Antietam — are actually further from D.C. than Baltimore is.

Then one evening, we were for some reason talking about a family trip to Ireland that we’d taken pre-pandemic. The kid mentioned offhandedly that his favorite thing about Ireland was the giraffes — I’d taken him to the Dublin Zoo, where they have giraffes, but we don’t have any giraffes at the National Zoo in D.C. I realized that they do have giraffes at the Baltimore Zoo, so off we went. After the zoo, we went down to the harbor to get a burger at Shake Shack and saw these weird electric pirate boats and took one out for a spin. The kid loved the pirates and wanted to go back to Baltimore, so we did the Aquarium (and the pirate boats again). And then another weekend we did Port Discovery (and the pirate boats). I also ended up getting vaccinated at a National Guard clinic at M&T Bank Stadium. Baltimore is really close!

But beyond my personal experience, the main reason the pandemic should increase the salience of CSAs is that it’s clear at this point that remote work is going to be somewhat sticky. I’m not saying all companies will go fully remote, but some will. And some will go partially remote. There’s going to be an increase in the number of people who want to live within a day-tripping range of where their industry is located, but not necessarily commute to the office every day. That means probably a flattening of the gradient so there’s not as much differentiation between inner-ring suburbs and further-flung ones. And it also means that satellite towns just a bit outside the normal commuting range probably become more desirable. In other words, it’s going to be a CSA world in which more people with “D.C.”-type jobs live in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania or Queen Anne’s County on the Eastern shore, only coming to town occasionally.

And the region should embrace that.

Making Baltowashington Great

I do think one reason I had such a hard time coming to terms with the idea of a unitary metro area is that ours doesn’t really have a name. The CSA version of Chicagoland is just also Chicagoland, with a slightly more expansive definition. And San Francisco + Oakland + San Jose + Silicon Valley = the Bay Area.

We could probably use a name that doesn’t just involve hyphenating Baltimore and Washington. That said, I’m not sure what the name should be. We’re the Chesapeake region (except not the part on the eastern shore of the Bay).

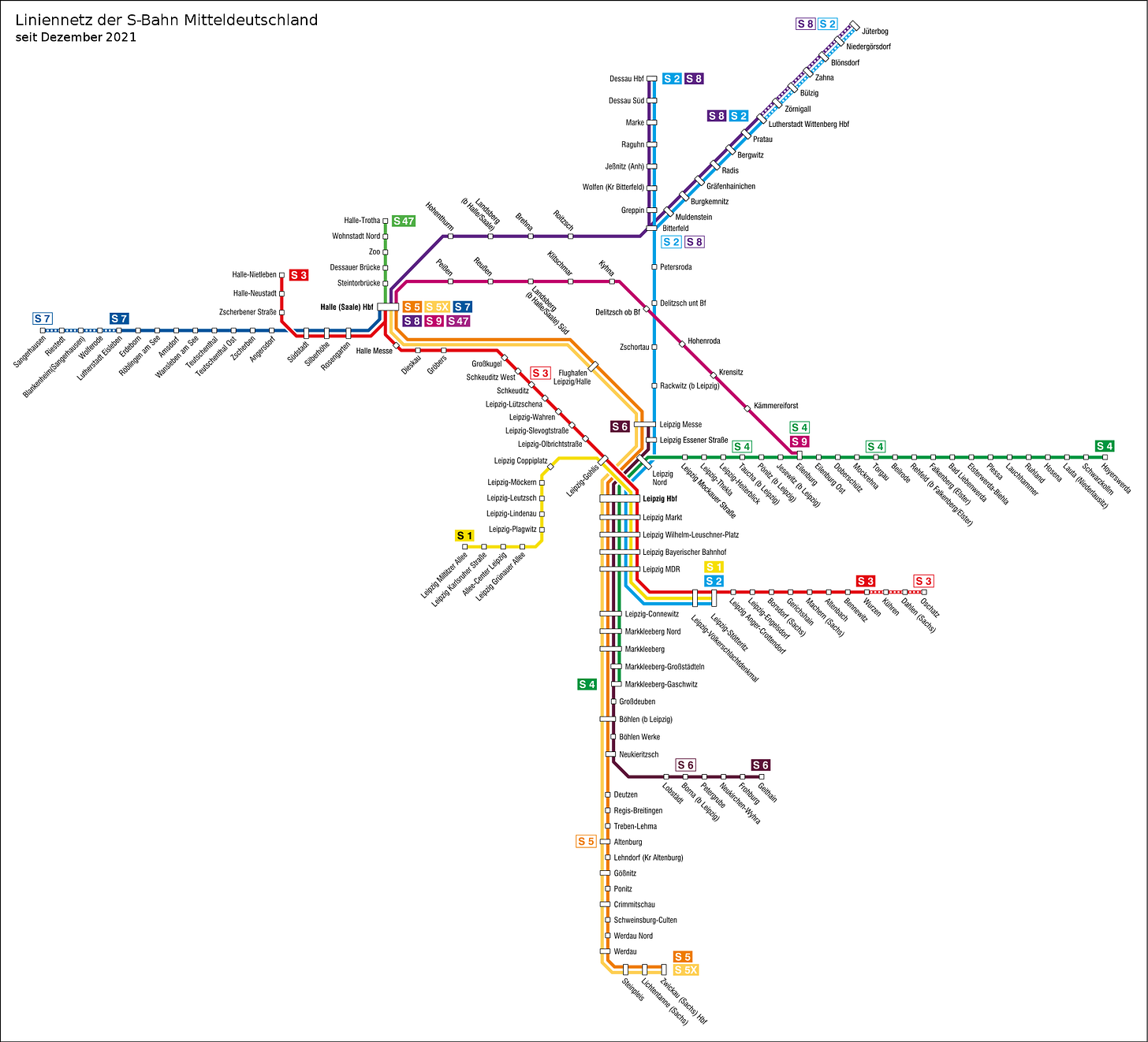

But beyond a name, what we really need to do is to improve the transit connections throughout the region. Not particularly because we need to make it easier to go from Baltimore to D.C. by train (which is actually already pretty easy) but because we need to make the suburban connections more seamless and robust and location agnostic. The key is to take our current U.S.-style commuter rail connections and make them something more like a German S-Bahn, with the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland in the Leipzig/Halle area as a particular inspiration because that’s another bipolar metro area that has no name.

S-Bahn runs on a mainline rail just like American commuter rail service. So what’s the difference?

S-Bahn runs through city centers rather than stub-ending and turning around.

S-Bahn offers all-day frequent service like mass transit, not highly directional peak service at rush hour.

S-Bahn uses electric multiple units to rapidly accelerate or decelerate while making station stops, thus making frequent stopping viable.

S-Bahn fares are the same as what you’d pay to travel the same distance on any other mode.

S-Bahn maintains low fares and frequent service by operating without conductors — just a single train driver and occasional proof of payment spot checks.

Infrastructure upgrades

The good news is that we have the outlines of the infrastructure for a Chesapeake Region S-Bahn. The MARC Penn Line runs from Perryville, Maryland through Baltimore and then down to Union Station in D.C. The MARC Camden Line runs from Baltimore to Union Station. Then Virginia Rail Express runs from Union Station through L’Enfant Plaza, Crystal City, and Alexandria before diverging into two lines, one that goes to Manassas and the other bound for Fredericksburg. There is also the MARC Brunswick line which goes from D.C. north and west of the city before branching to Martinsburg, West Virginia, and Frederick, Maryland.

And crucially, unlike a lot of American cities (Boston, New York, Los Angeles), D.C. doesn’t need a giant new tunnel downtown to through-run the trains.

Union Station has several through tracks, and there’s an existing tunnel that connects it to L’Enfant Plaza south of downtown and then to a bridge over the Potomac into Virginia. The problem is that bridge, which is currently used by VRE trains and Amtrak trains and also CSX freight trains, doesn’t have the capacity to increase frequency, a core goal of through-running.

So broadly speaking, we need a new bridge.

The local bigshots at the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments are pushing for this, which is good. But this is the kind of situation that needs bigger changes to make the gains. If you build a bridge, that costs a lot of money and increases ridership a bit. If you invest in electrification (on the Camden and Brunswick lines and the VRE — Penn Line is already electrified), EMU trains on all lines, and level boarding platforms (so people don’t need to use stairs, reducing station dwell times and improving accessibility), then the trains go faster. Faster trains mean you can run the trains more frequently without increasing your costs (and the tunnel allows for more frequency), and the improvements to both speed and frequency improve ridership. Then operational changes so you don’t need conductors lets you cut fares — which further increases ridership.

The hope then is that these multifaceted investments in increased ridership make a sound case for actually running more trains, further increasing frequency, and making the service more useful to everyone.

The goal is to serve what TransitCenter calls “all-purpose” transit ridership, not just 9-5 commuters. In other words, people who live in the suburbs should find the train to be an appealing option for an occasional trip to a museum or cultural attraction in central D.C. or Baltimore. If you live near a train station and your friend also lives near a train station, then riding the train for a social call so you can get drunk with a clear conscience should be a plausible option. This has always been a superior vision for transit since the strict 9-5 commute was just the preserve of a privileged minority of the workforce. The people serving coffee or cleaning buildings or working in schools and hospitals never worked those hours. But with the white-collar workforce now becoming more flexible, there’s more need than ever for flexible transportation infrastructure. That includes not just these hard changes, but also institutional changes in how transit systems operate.

Fare unions for America

A more integrated region means a different approach to fares. Again, I’m drawing inspiration from Germany where they have an institution called the verkehrsverbund, which I’ve seen translated as “transportation association” or “fare union.”

If you look at the Rhine-Ruhr metro area, there are a lot of small cities and also a lot of different transportation services — S-Bahn trains, U-bahn trains, trams, buses, all kinds of things. But the fare you pay is not determined by what kind of vehicle you take, how many transfers you make, or who operates which vehicle. Instead the whole region is divided up into zones, and your fare is based on how many zones you traversed.

Right now, going from New Carrollton to Union Station on MetroRail is a different fare than doing it on MARC. And taking the MetroRail to New Carrolton and then switching to the MARC to go to Baltimore is more expensive than taking the MARC all the way to Baltimore and passing through New Carrollton. The same SmarTrip fare card that I use for Metro and WMATA-operated buses works on the bus systems in some of the D.C. suburbs, but wouldn’t work on MARC or VRE and certainly wouldn’t work on the bus in Baltimore.

This is the kind of thing where getting everyone together in a room and agreeing on a way to set the fares and share the revenue across the region takes work. But in the end, making services more usable by more people will inevitably increase ridership and aggregate revenue. It’s worth putting in the hours to work it out.

A region growing together

This has been a lot of talk about German transit planning, but it’s for a reason.

Right now the D.C. suburbs are growing south of the city toward Waldorf, Maryland, and Dale City, Virginia on opposite sides of the Potomac. And they’re also growing northwest of the city toward Leesburg, Virginia, and Frederick, Maryland. But housing costs are currently above-average in basically all directions, and housing production has really slowed down since the good suburban locations have largely been filled in already, and the city proper is just too small to fill the void.

The direction northeast of the city pointing toward Baltimore is developed but under-exploited — neither set aside for nature nor intensively built-up in an urban style, even though the costs are high and there is mass transit infrastructure.

The Savage MARC station between D.C. and Baltimore has an awesome name, but it’s surrounded by a park-and-ride lot and some generic strip mall stuff. You should be able to build tall apartments and townhouse clusters near these stations — not with the expectation that people will be living car-free but thinking that it might work for a lot of one-car households who do many day-to-day errands on foot in the manner of the 15-minute city and can also ride trains to lots of regional destinations.

This is a zoning issue and a transportation planning issue, but I have also come around to the idea that it’s a mentality issue.

If you think in terms of a consolidated metro area then a place like this in Howard County is actually the center of the metro area and deserves to be a locus of intensive development.

In a world that’s super-oriented toward downtown commuting, Savage isn’t super-convenient to either city. But in a world where people aren’t commuting as much but still value cultural amenities, it’s close-ish to tons. And you could easily take meetings or do lunch in either city or, with through-running, you could get down to the Pentagon or the new Amazon complex in Virginia. All the stations along the two MARC lines should be little mini-towns that anchor the continuous urban zone and provide an additional dimension of housing growth to complement the ones we already have.

Obviously the region as a whole crosses the Maryland/Virginia boundary, has the District of Columbia as a core element, and reaches into little bits of West Virginia and Pennsylvania as well. But the key area is really in Maryland, and at this point, virtually all of Maryland’s population is inside the Combined Statistical Area.

Larry Hogan has so far given the state two terms of the kind of “do nothing” moderate-Republican-in-a-blue-state governance that voters seem to like. But there’s plenty of fruit here to be picked by a leader with a bit more vision.

First off, whoever decided to use “μSA” as the acronym for Micropolitan Statistical Area was clearly really proud of themselves for that one.

Second, as a Texan who was born in the DFW metroplex, when I moved to the DMV I was floored by how close Baltimore was. It seemed obvious to me that DC and Baltimore would be considered twin cities had they come into existence a century later than they actually did.

“In D.C. we have a popular football team.”

Citation needed.