Homelessness is about housing, not addiction or mental health

California and New York have unusual housing scarcity, not unusual levels of mental illness

A lot of people experiencing homelessness are also struggling with mental health problems or with substance abuse issues related to alcohol or hard drugs. That’s especially true of the subset of the homeless population that a middle-class person is likely to encounter in their day-to-day experience — you see troubled people who are acting out or the chronically homeless encamped on the streets, but not a single mom sleeping in a car in a Walmart parking lot.

This relationship, which is real enough, often leads people to the conclusion that addiction and mental health issues are the root causes of homelessness.

I was recently reading Jennifer Hochschild’s new book “Genomic Politics” about public views of the use and abuse of genetic science, and as an example of an extremely optimistic view, she quotes someone saying we’ll be able to eliminate homelessness with germline editing that eliminates schizophrenia. That’s a pretty fanciful outlier view. But I think it illustrates the problem with the treatment-focused view of homelessness, which is that it encourages paralysis and inaction on day-to-day housing supply solutions that ordinary people have a lot of control over, while it encourages those same people to think of themselves as being very generous in their support for more investments in treatment.

The truth, though, is that we don’t have a genetic magic wand to address these issues. Mental health and substance abuse services are great, but also highly imperfect. Even wealthy people with plenty of access to these things struggle. And no matter what you spend, it’s hard to get people on treatment or recovery regimes when they don’t have a safe and reliable place to stay.

But the whole idea is more profoundly confused than that. If you bring three cookies to a group of four kids and tell them they should fight to see who gets the cookie, the smallest one probably won’t get a cookie. To conclude that small size is the “root cause” of cookielessness would be obtuse. The problem is that you didn’t bring enough cookies. Homelessness is about housing!

Where the unhoused are

The simplest way to see the problem with the mental health frame is to ask where the rate of homelessness is highest.

Greg Abbott, talking about the homelessness problem in Austin, said the city needs to “provide mental health, drug addiction help + job training skills.” Dianne Feinstein, admitting that homelessness is one area where California needs to do better, says that “the root causes of homelessness vary & include mental illness, drug addiction & poverty.”

But let’s think about this for a second. Why is it that homelessness is a big issue in Austin but not in other Texas cities? Is Austin less skilled than other parts of Texas? The same question for Feinstein — California isn’t a poor state, so why does California have an unusually high rate of homelessness? Does the nice weather cause mental health issues? The two states with the lowest rates of homelessness are Alabama and Mississippi — are they world leaders in treating drug addiction? None of that sounds very plausible. California has more homelessness than Texas because it’s more expensive. And Austin has more homelessness than other Texas cities because, unlike other Texas cities, Austin has very high housing costs.

Now that Milan’s on the team, we can do more data journalism here, so you can see that the statistical association between per capita incidence of serious mental illness and homelessness is extremely weak.

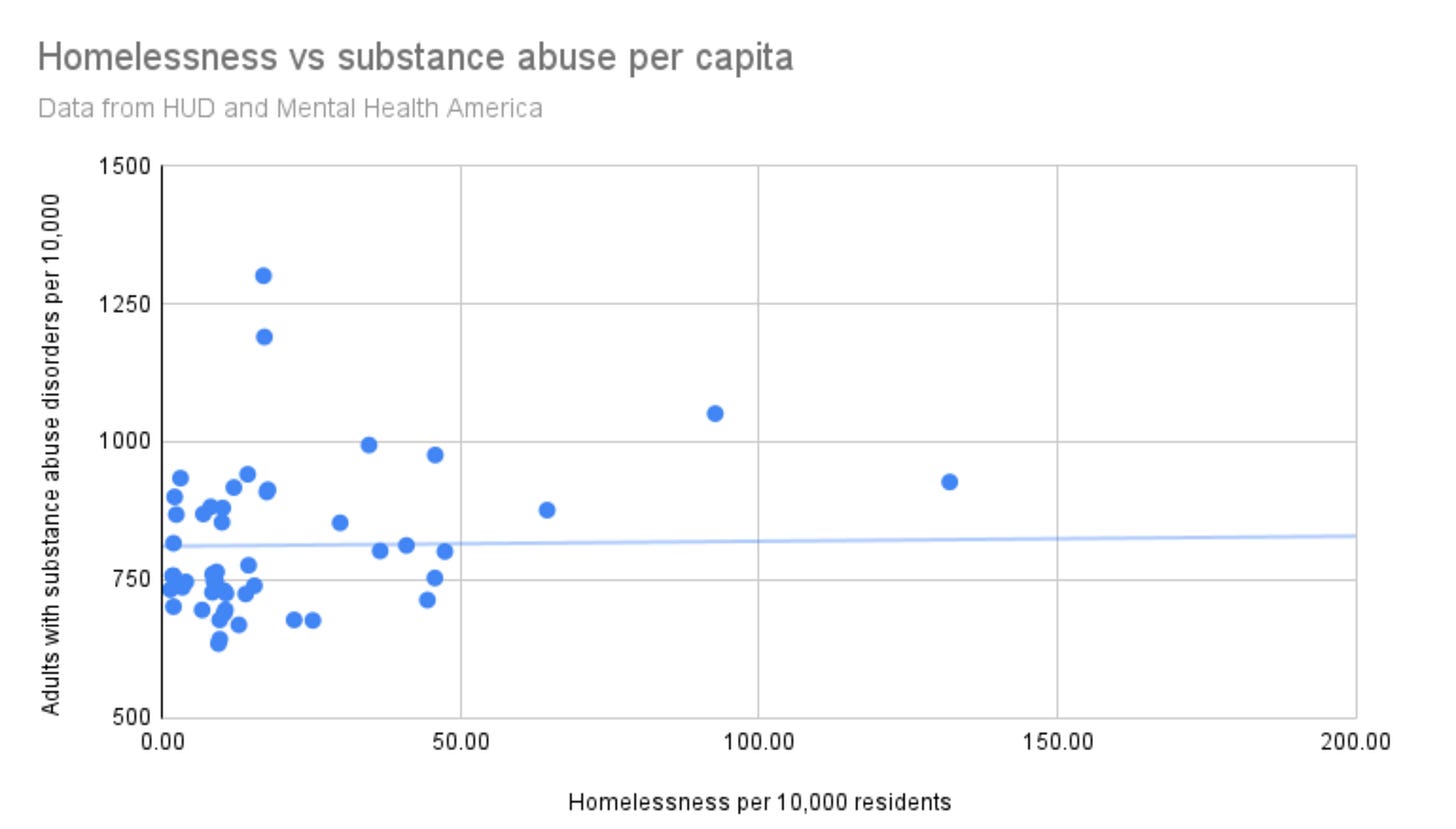

The same is true for substance abuse.

The top five states for homelessness are New York, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington. If D.C. were a state, it would be number one. That’s because these states are expensive. D.C. is especially bad because it has no low-cost rural fringe.

Obviously, it’s good to help people get treatment for their mental health and substance abuse problems. But that’s true in states with low homelessness, too. According to the CDC, the worst state for drug overdose deaths is West Virginia, and the worst for suicide is Wyoming. There are unhoused people in those states, but they are not places with particularly high homelessness rates. These are places that need help with mental health and drug addiction because people are dying.

Meanwhile, the homeless need homes.

Reverse causation

Even this kind of crude correlation almost certainly overstates the relationship between addiction and mental health problems and homelessness. That’s because not having a home is exactly the kind of thing that can cause or exacerbate mental health or substance abuse problems. It can also make it very challenging to get treatment.

This is why the “housing first” approach to homelessness originally pioneered in Utah and then championed by the Bush and Obama administrations worked well.

The basic philosophy is that, yes, your typical homeless person is experiencing a lot of problems. But rather than try to fix all those problems, you should get that person a place to live. Just doing that mechanically reduces costs elsewhere in the public sector in terms of law enforcement and emergency medical services. And then once the person is housed, you have a much easier starting point for something like “find a job” or “take your medication on a regular schedule.” It’s good to have an address, a place to store clothing and other possessions, and regular access to a bathroom.

In the most optimistic studies, this approach actually saves money purely through offsetting cost reductions. Some more recent studies are less optimistic about the cost-benefit analysis, so I now try to restrain my claims somewhat.

But I would still point out that getting good treatment for addiction is a non-trivial problem. We see very wealthy and privileged people struggling with drugs and alcohol, too. That’s not to say we shouldn’t fund services for those in need. But it’s a reminder that we should temper our expectations on that front somewhat. Dealing with these issues effectively is a non-trivial problem, and in some cases, it’s genuinely not clear how to do it. By contrast, you never meet a rich homeless person, and while I do not personally know how to build a house, we as a society have pretty much mastered this.

Housing solutions are easy if you want them

Greg Abbott’s history of picking on Austin’s liberal city government over its homelessness problem bugs me because the homelessness problem really is the fault of Austin’s liberal city government.

But instead of acting like a bleeding heart who thinks the city needs to do more to fund drug treatment, what Abbott needs to do is introduce Travis County to a little thing called the free market. Over the past 30 years, demand for living in Austin has soared. And while construction in Austin has soared along with it, it’s still the case that there are massive regulatory barriers to more housing. Of course, Austin is not the only American city that has this problem. But it is the one where, in some ways, I see the most politically straightforward solution to the problem, which is to leverage Abbott’s love of owning the libs in general (and Austin in particular) into the Texas GOP preempting local land use regulations.

I’ve written plenty of times here about land use regulation and won’t bore you with my same sermon on this again.

Instead, I just want to note a few things. One is that we’re starting to see these issues gain traction on the left. The YIMBYs scored a big win in California recently, and while I don’t think any single bill will solve California’s housing crisis, I do think we now see the emergence of a pro-housing coalition in the California legislature. We’ve had several sessions in a row in which at least some pro-housing legislation moves, and really that’s what it takes. And Jerusalem Demsas has two great recent pieces about the myths of gentrification and why you shouldn’t identify gentrification with new construction.

Unfortunately, as YIMBYs have started to make headway in progressive circles, we’ve seen a conservative backlash from Tucker Carlson and others. But there are forces pushing back against that. Tim Lee at the new center-right policy blog Full Stack Economics recently did a great overview of the new literature on how new “luxury” housing helps everyone. Ed Glaeser from the Manhattan Institute and Jim Pethokoukis from AEI recently did a good podcast on housing costs.

Homelessness is caused by scarcity of dwellings. The people who suffer the most from housing scarcity tend to be people who have other problems, too. But in a world of housing plenty, those problems don’t need to generate widespread homelessness. Conversely, if there aren’t enough homes to go around, then no amount of mental health services is going to fix the fact that someone is stuck without a place to live.

I worked in the Texas Legislature last session and one of my bills was to help facilitate free market zoning reforms (HB 2989/SB 1120). My goal, working with advocates, was to try the exactly the political strategy you laid out in today's post.

A Democrat filed the bill in the Senate and a Republican in the House and we had an impressive cross-ideological stakeholder coalition behind it. We found there was very, very little appetite for reform from the Republican members. The House Committee hearing was a shitshow and the members were way more receptive to citizen's concerns about neighborhood character than high-minded ideas about the free market.

The Senate companion bill didn't even get a hearing, as the (very conservative) Republican Committee Chair opposed it. It became just another front in the anti-city culture war. Republicans were more willing to listen to a lobbyist hired by a Austin-based left wing activist who opposed zoning reform than they were willing to listen to the Realtors, Builders, and Habitat for Humanity.

1st mistake. Austin is expensive because its desirable. Homeless are attracted to Austin because it's desirable. Not all desirable and expensive cities have large homeless populations.

2nd mistake. Everyone who speaks about homeless conflates two completely different populations. The transitory homeless who get counted but we never see, and the visible homeless we do see.

3. The transitory homeless make up at least half of all homeless. These are people who get evicted, or lose a job, and are usually out of homelessness in a few weeks. They are the ones who will move from expensive places to less expensive places for jobs.

4. The visible or chronic homeless are the ones we see on the streets of San Francisco. They are there because of mental health issues and substance abuse. They are attracted to place with generous services, nice weather, and lax drug policies.

5. A significant portion of the chronic/visible homeless refuse housing. The success rates when in drug programs are less than 50%. And this is taking into consideration that the most addicted won't even attempt counseling.

Now, is housing part of the solution. Yes, obviously. But the real solution to homelessness is a combination of housing, treatment, and enforcement.

A fixation on lowering the costs of housing will help the transitory homeless, but to make dent on our visible homeless, some tough love is needed.