The bizarre myth that Ancient Greeks couldn't see blue

Don't overrate the power of language to shape minds

Here’s something you may not know: pre-modern people couldn’t see the color blue.

One reason you probably didn’t know this is that it isn’t true. But that hasn’t stopped a lot of people over the years from claiming it’s true. Indeed, I recently learned via Noah Smith’s Twitter feed that there’s a whole cottage industry of people claiming that before the modern world, nobody could see blue.

“There’s Evidence Humans Didn’t Actually See Blue Until Modern Times” [Science Alert, 2018]

“No one could see the colour blue until modern times” [Business Insider, 2015]

“Why the Ancient Greeks couldn’t see blue” [ASAP Science, 2019]

“Why ancient civilizations couldn’t see the color blue” [Good, 2020]

“Could our ancestors see blue? Ancient people didn't perceive the colour because they didn't have a word for it, say scientists” [Daily Mail, 2015]

What’s going on here? Why are all these people writing articles claiming that ancient people couldn’t see blue?

It is true that lots of ancient languages didn’t have a word that refers to the exact part of the color spectrum that we call “blue” in English. And there is also some evidence that a person’s native language influences their perception of colors. But for some reason, large swathes of humanity are strongly predisposed to believe the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis that human thought is really controlled by language. It’s an idea you’ll find in “1984,” where the Party was going to make dissident thought impossible by forcing everyone to use Newspeak. It’s also one of the reasons we have such ferocious battles over whether to call people “illegal aliens” or “undocumented immigrants.”

The truth, though, is that while language influences cognition, the influence is much milder than most people seem to think. Ronald Reagan said “I believe in amnesty for illegal aliens,” which is cancel-worthy verbiage these days. But he then delivered on a large-scale path to citizenship for a huge population of undocumented immigrants. The dated-to-our-ears language didn’t prevent him from taking a humane view of the situation, and a generation of linguistic reform since then hasn’t conjured up a congressional majority for better policy.

Yet people are so in the grips of Sapir-Whorfdom that they were willing to endorse an incredibly extreme claim — that premodern people couldn’t see the color blue — on the basis of some arguably mangled linguistic history and an apparently fake experiment featuring one small population in Namibia.

Into the wine-dark sea

A common introduction to this topic is the observation that the Homeric epics include many references to the “wine-dark sea” but not a single use of any word that translates to “blue.”

This has bothered scholars for a long time, and one theory is that Ancient Greek wine was blue.

Further study has revealed that it’s fairly common for pre-modern languages not to have a word for the color blue, so the dominant interpretation of the Homer situation is that he doesn’t call the sea “blue” because Ancient Greek did not have a word for blue.

At this point I have to concede that I do not have any direct knowledge of Ancient Greek. At least one bona fide Hellenist, Peter Gainsford, says people are misinterpreting the Ancient Greek color words, and the terms “kyaneos” and “glaukos” cover most of the color space denoted as “blue” in English.

Rather than adjudicate this fully, I think we should say that there is a clear consensus that Ancient Greek color words do not correspond one-to-one to the color words of modern English. In general, different languages have different basic color terms and also differ in the number of basic color terms. Some languages have a system that distinguishes light from dark and red from not-red. The concept of “orange” as a distinct color seems to be relatively rare and also of recent origin. Chaucer described the color of a fox’s fur as “betwixe yelow and reed.” Shakespeare used the word “orange” to refer to the fruit, and he several times described things as “orange tawny” in color, but it’s only after his time that unmodified “orange” became a basic color word.

But per Chaucer, it’s not as if people couldn’t tell that some things have a color that blends yellow and red. Some Middle English sources use the word “geoluhread” for orange. And when English-speaking people became familiar with the once-exotic fruit the orange (whose name seems to come from distant Dravidian languages), they could see what it looked like, and eventually the name for the fruit became the name for the color.

Different languages use different words

This is a map of the inner portion of the Moscow Metro. It shows a purple line, a green line, an orange line, a red line, and a yellow line, but to distinguish line three from line four, I’d have to say that one is the dark blue line and one is the light blue line.

In Russian, though, they have actual different words for these colors. Line four is голубо́й (goluboy) and line three is си́ний (siniy).

But here I think it’s obvious to everyone that just because English doesn’t make a linguistic distinction between goluboy and siniy doesn’t mean that English speakers can’t see that these are different colors. If an American goes to Moscow, his problem navigating the metro is going to be that the station names are written in the Cyrillic alphabet; the fact that the lines are different shades of blue is interesting, but you’re not going to mix them up. The color space is just a lot richer than our vocabulary of basic color words.

On a computer screen, we work with the RGB color system where each pixel has a mix of red, green, and blue light. In standard HTML you can represent nearly seventeen million distinct admixtures of RGB light in terms of a six-digit hexadecimal code. And with the assistance of a handy random number generator, here are fourteen different colors.

Now you can see that some of these colors like D3D726 and C8CB28 are similar to the point where I could not easily describe to you the difference between these two different broadly olive greenish-yellow tones. But they are different, and if you can’t see that they’re different, that just goes to show you need a better computer monitor.

Nick Enfield is a professor of linguistics at the University of Sydney and the author of the new book “Language vs. Reality: Why Language is Good for Lawyers and Bad for Scientists.” And he observes, among other things, that when it comes to the visible light spectrum, all of human language is just a bit impoverished compared to human eyes.

You can see why natural languages don’t have words for all these colors — it’s hard to imagine a situation in the broad sweep of human history where being able to convey to someone that something was EE814B rather than D56E3C would have been important. That’s especially because outside the context of a computer screen, the color of things is always changing based on the ambient light. You might want to talk about a fruit being green vs. red as a way of indicating what fruit you’re discussing. But the exact shade of red will vary based on the time of day and other factors, so there’s no point in being incredibly precise about it. We now directly manipulate light on our screens, so we needed to invent the hexadecimal web color system.

But here’s the point: you do not need to have memorized these hexadecimal colors to be able to distinguish between the shades. We invented the nomenclature when a situation arose that made drawing the distinction important.

There is some evidence that a person’s native color vocabulary influences their color perception, but that influence is quite limited.

Fake and real science of linguistic color perception

Linguistics aside, where did people get this bizarre idea that if a language didn’t have a distinct word for “blue,” the people who spoke it couldn’t see blue?

This seems to go back to a 2012 Radiolab episode about colors that goes through the linguistic facts about color words and then discusses Jules Davidoff’s research on color perception among the Himba, a small population of semi-nomadic people living in Namibia. Here is Business Insider’s gloss of Radiolab’s gloss of Davidoff’s research:

When shown a circle with 11 green squares and one blue, they couldn’t pick out which one was different from the others — or those who could see a difference took much longer and made more mistakes than would make sense to us, who can clearly spot the blue square.

But the Himba have more words for types of green than we do in English.

When looking at a circle of green squares with only one slightly different shade, they could immediately spot the different one. Can you?

Business Insider’s writeup features these two images that come from a 2011 BBC documentary titled “Do You See What I See?”

The problem, as linguist Marc Liberman discovered when looking into this for his blog Language Log, is that the experiment shown in the BBC documentary is a dramatization, not Davidoff’s actual research, and “the description of its ‘results’ was invented by the authors of the documentary, and not proposed or endorsed by the scientists involved.”

There is, however, non-fake research on this done by Jonathan Winawer, Nathan Witthoft, Michael Frank, Lisa Wu, Alex Wade, and Lera Boroditsky that reached a much more restrained conclusion. Remember the Russians with their two words for blue?

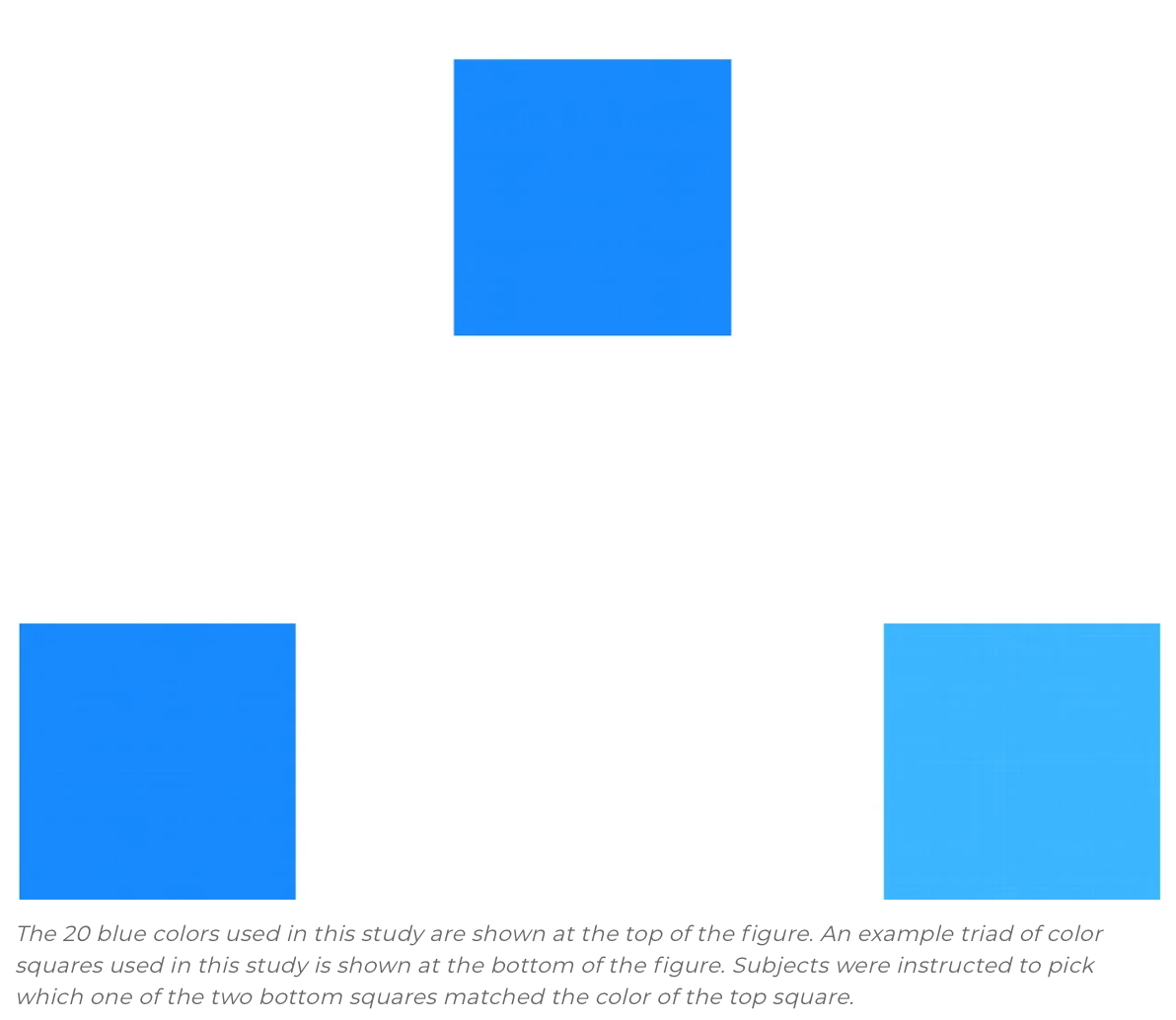

These researchers did an experiment in which the subjects were shown a triad of blues, one square on top and two on the bottom. One of the bottom squares was always the same blue as the one on top and the other bottom square was different. The task was to identify either the left square or the right square as matching the top square, and the goal of the experiment was to see how quickly people could do this and how their speed related to how objectively distinct the shades were.

So what did they discover?

For all participants, reaction time was a function of how objectively different the shades were — the more similar the blues, the harder for people to pick.

Native speakers of Russian displayed a reaction time discontinuity between siniy and goluboy shades — they were better at distinguishing a light blue from a dark blue than they were at distinguishing a dark blue from a very dark blue.

Native speakers of English did not display this discontinuity. For them, reaction time was a pure function of the objective distance between the colors.

That’s it! That’s the difference.

Now to some people, this is very striking. I read about this experiment in Guy Deutscher’s book “Through the Looking Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages.” But I have to say, I don’t find the fact that reaction times in a color-identification test are slightly faster across the siniy/goluboy boundary if you speak Russian rather than English to be all that mind-blowing. There’s a reason the version of this research that went viral was the fake claim that people without a word for “blue” couldn’t see blue. That is a really striking and crazy fact about the world (except that it’s not true), whereas the small but statistically meaningful difference in the color shade test is good science but doesn’t exactly knock your socks off.

Language doesn’t matter that much

I bring this all up not so much because I’m interested in the Moscow Metro but because I think there are big categories of political argument that are fundamentally misguided and driven by a shared left/right misconception about the power of language.

On the one hand, you have a lot of progressives who badly overrate the power of linguistic reform campaigns to drive meaningful change in the world. I think this was really the core of the argument over “political correctness” that I remember from the 1990s. And some people on the left today believe in it very strongly. Here’s Robin DiAngelo in her latest book:

Language is not neutral. The terms and phrases we use do not simply describe what we observe. In large part, the terms and phrases we use shape how we perceive or make meaning of what we observe. This is why the terms used for marginalized groups are constantly being challenged and negotiated. Consider the difference between “illegal alien” and “person entering the country illegally.” Or the difference between “China virus” and “COVID-19.” Or trace the trajectory of changes over my lifetime of this set of terms: “bum,” “tramp,” “wino,” “hobo,” “vagrant,” “homeless,” “persons without housing.” There are significant differences between the images and associations at the start of that list and the end. Those differences impact our perceptions and have real consequences for how people are treated and the resources they receive.

This seems really wrong to me. As discussed above, Reagan was able to deliver “amnesty” to “illegal aliens” while Barack Obama and now Joe Biden have failed to create a “path to citizenship” for “undocumented immigrants.” The verbal swap does not contain magical power to shift the political landscape. Similarly, despite DiAngelo’s claims, the truth is that American public policy has become more hostile to the marginally housed over time because zoning has become more stringent.

And I think she misreads the “China virus” case.

When I hear someone talking about “the Jews” rather than “Jewish people,” it trips my anti-semitism alarm. But that’s not because I think the phrase “the Jews” is inherently harmful to Jewish people. It’s because I am aware that in 21st century American English, the phrase “the Jews” is not considered the conventionally polite way to refer to Jewish people and someone deliberately flaunting that norm probably does not mean us well. Similarly, if you met someone who was running around talking about “negroes” all the time, you’d infer that guy’s a huge racist. But that’s not an inherent property of the word (Martin Luther King used it all the time!), it’s a sociological fact about what kind of person would deliberately defy the relevant convention.

Stephen Pinker talks about a euphemism treadmill; terms like “concentration camp” and “ethnic cleansing” that arose as efforts to pretty up horrifying acts soon become the names of horrifying acts. Words just don’t have that much power over our minds.

Failure to recognize this creates two problems. Progressives get very invested in “inclusionary” linguistic concepts that in practice exclude older and less-educated people. And conservatives fall prey to moral panics where they assume anyone who wants to use up-to-date language is thereby endorsing the most absolutely extreme ideological claims of anyone who uses that language. The fact, though, is that words are always changing their meaning (John McWhorter’s “Words on the Move” is my favorite account of this), and it’s just not that big of a deal unless you happen to be taking a weird color-matching test on the computer.

Thank you, this is one of my personal bore-people-to-death-at-parties hobby horses: it’s absolutely common folk wisdom around the “left”, especially (and ironically) in academic contexts that that Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is not just true but settled and accepted science, which is crazy-making since the actual experimental and empirical evidence for it is… “highly contested” is about the kindest term I could possibly use.

What it actually is, of course, is a belief in _magic_, specifically of a strain that Ursula LeGuin poetically described in “A Wizard of Earthsea”: things have their common names and their secret true names, and if you know the latter you can control them. It makes for dazzling fantasy literature but rather less dazzling political practice.

You can see through older film and photography that our worlds rich and vibrant colors are in fact quite a recent development. I have no idea why Matt is trying to obscure this. Lying about colors won’t make ‘birthing people’ sound any better to most ears.