A good neighbor policy for the 21st Century

The U.S. should prioritize prosperity in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean

I wrapped up trips to Maine and Texas with posts offering policy advice to those states, and I had Mexico on the brain while I was in the country last week.

Unfortunately, I don’t understand the domestic political situation in Mexico nearly well enough to grasp what ideas are and aren’t in the realm of plausibility. I also don’t have any good ideas for addressing what seems like Mexico’s biggest problem: the endemically weak state capacity to take on drug cartels.

But I do have advice for the United States of America, which is that we could and should revise our own trade policies to be more favorable to Mexico and the members of the awkwardly named DR-CAFTA group (the Dominican Republic and most of Central America). In negotiating NAFTA and CAFTA, and then especially in revamping NAFTA into USMCA, we’ve consistently acted like the main point of negotiating trade deals is to help American exporters, using the lure of access to the American domestic market to try to bully smaller countries into taking more American agricultural exports or adopting our intellectual property rules.

That’s all very shortsighted. The main point of forming a regional trade bloc with our Latin American neighbors should be to turn these basically friendly, basically democratic states into rich and successful friendly democracies. We should be building an awesome club that other countries like Jamaica want to join. We should be pwning Cuba by creating many, many nearby economic success stories that leave them in the dust. And we should be countering the China-Russia axis with as many democratic success stories as we can. Especially because what happens in Mexico and Central America directly affects Americans even more than what happens in Ukraine or Taiwan.

Reassessing our policy toward our neighbors should start with re-considering what the 1990s free trade consensus got wrong, but also what it got right.

Trade is good, China is bad

Both NAFTA and the Permanent Normal Trade Relations with China were products of the bipartisan pro-trade consensus of the 1990s, which did get something really badly wrong: the idea that economic integration would promote political liberalization in China.

When Bill Clinton signed the bill establishing PNTR, then-Speaker Dennis Hastert remarked that the arrangement wasn’t just about dollars and cents. “Know what? We open it up so that we can exchange ideas and values and culture,” Hastert said. “And that's an important thing.”

Clinton agreed at length in his remarks:

Of course, opening trade with China will not, in and of itself, lead China to make all the choices we believe it should. But clearly, the more China opens it markets, the more it unleashes the power of economic freedom, the more likely it will be to more fully liberate the human potential of its people. As tariffs fall, competition will rise, speeding the demise of huge state enterprises. Private firms will take their place, and reduce the role of government in people's daily lives. Open markets will accelerate the information revolution in China, giving more people more access to more sources of knowledge. That will strengthen those in China who fight for decent labor standards, a cleaner environment, human rights and the rule of law.

This was really wrong.

It’s tough to argue that Chinese economic development was bad per se since it lifted so many people out of poverty. But the idea that it would promote political reform was not just overstated, but directionally wrong in a discrediting way. Again, it’s hard to regret Chinese economic development. But it’s easy to say that, to the extent the United States could have instead directed that development toward countries like Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala, it would have been better.

This brings us back to what the free traders got right.

It is good, economically speaking, to outsource low-productivity work to poorer, lower-wage countries. That lets your country get more and cheaper stuff and also allows you to reallocate your own labor supply toward other more pressing needs. The moderately bad macroeconomic management of 2001-2007 followed by the catastrophically bad macroeconomic management of 2008-2018 managed to disguise this by keeping the labor market in a state of near-constant recession or quasi-recession. But today’s fully stimulated economy reminds us that in a properly managed economy, “jobs” are not the scarce commodity; actual goods and services are. Trade relationships let poor countries get richer by importing capital and know-how, and they let rich countries get richer by reducing supply-side constraints.

In other words, there’s nothing wrong with trade. But there’s plenty wrong with a situation in which China is growing so much faster than friendlier, more democratic countries that also struggle with poverty and underdevelopment.

While there is obviously trade between the United States and Latin America, Perot’s “giant sucking sound” pulling jobs south didn’t materialize on the scale he imagined, in part because the jobs went to Asia instead.

China competes with other exporters

The PRC has made a lot of investment in strategic economic sectors where we compete with them more or less directly. And in those high-end sectors — airplanes, software, AI, next-generation energy, etc. — we ought to be competing. We are a rich country and we want to be at the economic frontier.

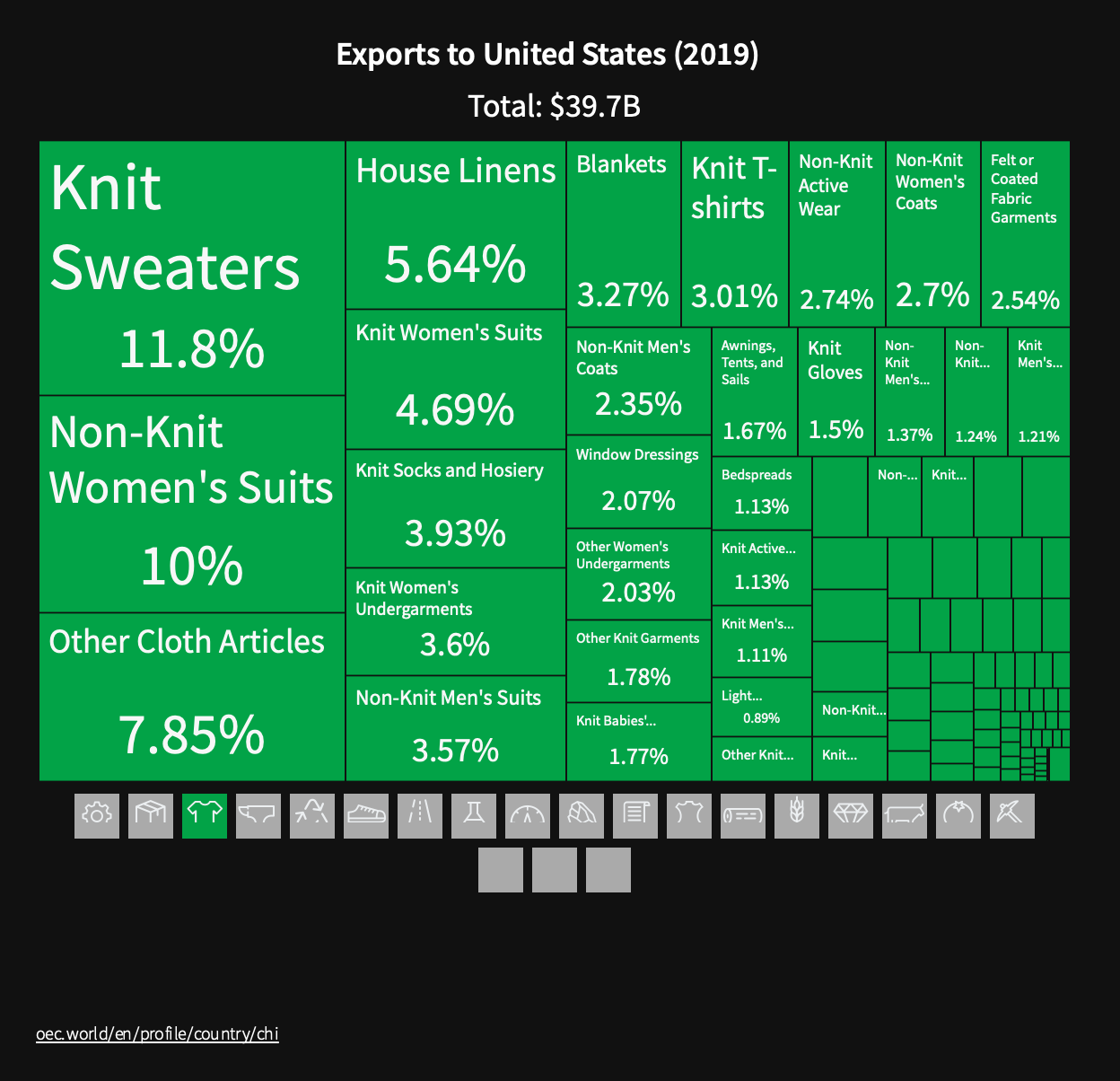

But China also exports a ton of textiles to the United States.

This is not really an area where we can or should be looking to compete. Apparel manufacturing is a poor country’s game.

But China is competing with other countries to serve the American market. Mexico makes textiles, too, but their textile exports to the U.S. are dwarfed by China’s. Half or more of the Mexican labor force is in informal jobs, so while Mexico is a much smaller country than China, they are certainly not out of potential garment factory workers.

Guatemala is the kind of very poor country that should be champing at the bit to get on the industrialization ladder with a garment industry. But their textiles industry is tiny, with exports roughly equal to their banana industry.

We should be making it as easy as possible for our friends and neighbors to be the ones who capture these jobs. But instead, we’re monkeying around with the interest group politics of the American yarn industry.

“Yarn forward” is backward priorities

The point of forging free trade agreements with friendly nearby countries should be to give those countries priority access to the American market — an express lane that advantages them vis-à-vis China. And under NAFTA, apparel made in any member country was supposed to get tariff-free access to any other country.

But this was made more complicated with a bunch of rule of origin provisions that were tightened up in drafting USMCA. As the law firm Arent Fox explains, it’s not good enough for the t-shirt to have been made in a Mexican factory; they need to be made of North American yarn, which in turn needs to have been made of North American cotton:

The USMCA textile and apparel rules of origin are generally based on the “yarn forward” rule, which requires the formation of the yarn (spinning or extruding) and all processes following yarn formation to occur in the USMCA territory. Yarn itself is generally subject to a “fiber-forward” rule which means that the fiber must originate in a USMCA country and all processes are required to produce the yarn after that, e.g. extruding or spinning and any final processing must occur in the USMCA territory.

The yarn forward concept was originally pioneered in DR-CAFTA and it applies there, too. The rule has two impacts relative to simple free trade:

We get less apparel made by our regional partners and more made in China.

A larger share of that smaller pie is successfully captured by American cotton growers.

This is obviously not even close to being the worst set of priorities that cotton interests have imposed on the American government over the course of their sordid history, but it’s still really dumb. Promoting Latin American industrialization has wide-ranging benefits for geopolitics, for managing migration, and for helping America’s advanced industries find customers in a less poor hemisphere. Promoting cotton farming accomplishes nothing. These are classic, seasonal, low-paid “jobs Americans won’t do,” so we get H2A guest workers instead. There’s nothing wrong with that (it’s a great example of the economic benefits of immigration), but if foreign demand for U.S.-grown cotton diminished somewhat, that’s also fine.

But America’s policy toward countries that we supposedly have free trade with is full of this kind of weird bug. We’re driving ourselves crazy trying to stop poor Central Americans from migrating here in search of work, but we’re also blocking them from selling us sugar, which might give them more jobs at home.

Just be helpful

The old joke “poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the U.S.” exemplifies Mexico’s weak negotiating position in any kind of dealmaking with the United States of America.

And Mexico has its own share of self-driven problems. But the situation genuinely calls for some enlightened self-interest on the part of the United States and recognition that it would sincerely be really good for the United States if Mexico and its neighbors were enjoying more rapid economic growth. They ought to kick all the lobbyists out of the room at the U.S. Trade Representative’s office and try to make every provision of USMCA and DR-CAFTA as friendly to Latin American exporters as possible. If those countries want to open their markets in ways that American companies want, that’s great. They should do that. America is home to a lot of great companies. But the trade relationship should not be about the United States serving as muscle for our exporters — it should be about opening our markets wide open so that our neighbors have maximum ability to outcompete China for market share and grow.

And I would apply that same dictum to other areas. AMLO appears to be pursuing the very eccentric goal of halting crude oil exports in hopes of making Mexico self-sufficient in gasoline, rather than continuing with the current practice where Mexican crude is shipped to Asian refiners and Mexican gas stations import refined gasoline from the United States.

I have no idea why he thinks this is a good idea, but one challenge facing Pemex (the Mexican state-owned oil company) seems to be significant management problems at their existing refineries. If we have any smart people that we can send down to help out, we should. Mexico is very sunny, which is why I was there on vacation, but which also means we should be encouraging technology transfer to spur their solar industry.

The world of trade agreements is full of tedious details like the country of origin rules for fiber. The U.S. approach to the region tends to oscillate between Trump-style open bullying to try to crack down on migration and the Obama/Biden approach of talking a lot about root causes. But aid checks as a bribe to externalize immigration enforcement, while probably better than other available short-term alternatives, don’t actually address root causes. What would address them is genuinely prioritizing economic development, not in the sense of telling other countries what we think they should do (be less corrupt! make good decisions about everything!), but in the sense of tackling things that are genuinely under our control. That means opening our markets to as many exports as possible to give Mexico and our other neighbors the best possible chance of finding their own way to prosperity.

More growth and industrialization in this part of the world is one of the biggest possible geopolitical wins for the United States, and our top priority in every regional decision should be an honest effort to be a good neighbor promoting development rather than a petty bully.

“This was really wrong.”

I have a few quibbles.

Actually, a lot of quibbles.

It turns out that almost every sentence in that quote turned out to be correct *in part.*

The role of the state in the economy was vastly reduced between 1999 and 2008, and tepidly so between 2008 and 2015. State-owned enterprises have less of a stranglehold over the productive apparatus than before, and are much more market-oriented, especially those owned by the national government.

In addition, there are a great many more Chinese citizens for whom relative prosperity has brought a more liberal or global outlook, not only among the professional classes. The middle classes are also much more open and outward-looking.

This has lead to the growth of organizations promoting exactly the things outlined in the last sentence, few or none of which existed prior to 1999.

The real problem isn’t that the expected “natural outcomes” of liberalized trade with China didn’t materialize, but that the Party-State proved extraordinary adept at neutralizing those less conducive to its continued rule without actually killing off the overall benefits of (limited) economic liberalization.

Suffice it to say a lot of the outcomes of these trends are still very much up in the air.

This piece contains too much good common sense to be adopted clearly and widely as official policy by our politicians.