Getting back on track with the Latino vote

A decade of bad analysis built on a flawed analogy

Before smartphones and GPS, if you were traveling to an unfamiliar location you’d often have to rely on written directions. One thing that might happen is that, by mistake, you could take the wrong exit from the highway but otherwise start following the correct directions. So you make a left at the third light after the exit then go four blocks and turn left again and then right just before you pass an Exxon station and there’s the restaurant. But then you look around and see you’re not where you were supposed to be — you were trying to get to a diner reputed to have the best pancakes in the state, but you’re actually at a pizzeria, because you made a mistake several steps ago when you took that exit from the highway.

Now you have a choice: you can eat some pizza or you can break out your map and make your way to the diner.

But what you don’t want to do is pretend that you knew all along where the exit was, stroll into the pizzeria, and order pancakes.

This is what Democrats seem to me to be doing with the Hispanic vote as we head into the fall. A number of different pieces are falling into place to lead Democrats to basically correct conclusions about the Hispanic electorate. Catherine Cortez Masto’s weak polling in Nevada, Florida’s emergence as a safe GOP state, continued Republican gains in South Texas, and turmoil on the LA City Council after a bloc of Hispanic members were caught on tape making insensitive comments about everyone from Black colleagues to immigrants from Oaxaca.

But because people don’t like to admit they were wrong, many are downplaying the extent to which political choices made five to 15 years ago were based on incorrect ideas about this.

Recently, some on the left — including PRRI pollster Natalie Jackson and columnist Perry Bacon — have expressed annoyance that people have so much interest in the shifting non-white vote when, in Bacon’s words, “America’s problem is White people keep backing the Republican Party.”

I agree with Bacon’s bottom line about the centrality of the white vote to electoral outcomes. But I think he is underplaying the significance of the unexpected rightward shift in the Hispanic vote since the 2012 and 2016 cycles. Not because the number of people involved is so large in absolute terms, but because when you get off the highway at the wrong exit, this creates cascading problems for your effort to drive to your destination, even if the two exits aren’t very far apart.

A false analogy with Black voters

The problem is that five to 15 years ago, progressives started basing their vision of the future of American politics on a false analogy with the behavior of Black voters.

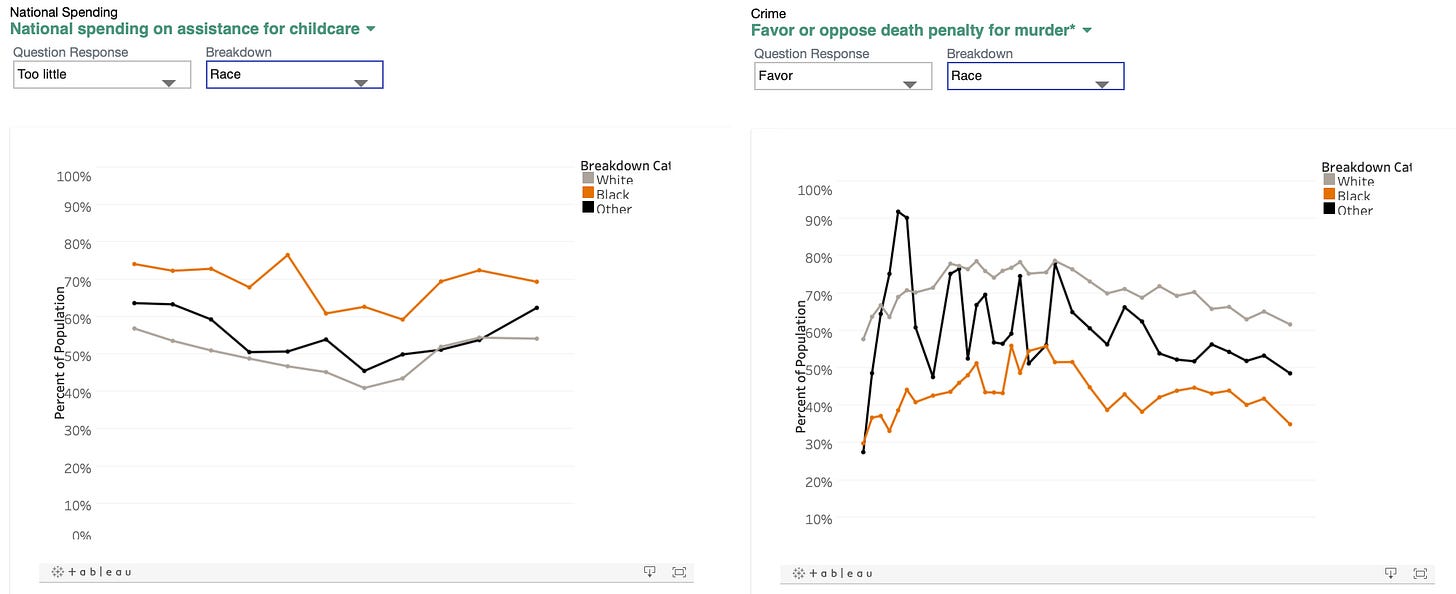

African Americans vote for Democrats in elections by overwhelming margins. As Bacon and Dhrumil Mehta outlined in this 538 piece years ago, this holds even though on questions that aren’t directly about party preference, Black political opinion is quite diverse. In the General Social Survey, for example, Black Americans display more progressive views on child care spending and the death penalty than do white Americans. But Black support for the progressive position on these issues is much lower than Black support for Democrats.

So what’s the deal? Well, as Bacon & Mehta recount in that piece, nearly 84 percent of Black respondents said they thought Donald Trump was racist. And people don’t like to vote for people who they think are racially prejudiced against them.

More broadly, as Ismail White and Chryl Laird document in their excellent book “Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior,” Black America has a whole set of social institutions that convey messages that they should vote for Democrats. In exchange, the Democratic Party is very attentive to these institutions. Democrats support HBCUs, they campaign in Black churches, and they support the drawing of majority-minority districts for state legislatures and the House of Representatives. In the modern highly polarized Congress, the Congressional Black Caucus stands out as a bastion of ideological diversity, including some very left-wing members but also many stalwarts of the moderate faction of the Democratic Party. That’s because even though Black Americans are to the left of white Americans, Black Democrats are more moderate than white Democrats because moderate Black people tend to overwhelmingly affiliate with the Democratic Party in a way that white moderates do not.

A lot of different things fall out from this dynamic, including:

Identity-based appeals are very important to securing the vote of the marginal Black voter, who is probably to the right of the marginal white voter on policy.

Because the African American electorate is so overwhelmingly Democratic, it’s probably worth caring more about turnout than persuasion, even though every persuaded voter counts for two mobilized voters.

As long as Democrats delivered on their core commitments to Black Americans, they could afford to blow off Black voters’ relatively conservative views on abortion and gay rights issues.

Changes in the Black population’s share of a given electoral geography are very predictive of changes in partisan election outcomes.

Consider Florida and Georgia. Florida is 17 percent Black, and Georgia is 33 percent Black. But if Florida were as Black as Georgia, Biden would have won it easily, even if you simply swapped white moderates for Black moderates. Politically moderate Black people think the Republican Party is racist and that Democrats care about them, and they vote overwhelmingly for Democratic Party candidates.

By contrast, as Eric Michael Garcia says, “there is no such thing as the Latino vote. There are Latino votes.”

This point is so correct and obvious, though, that I worry people are going to repeat the phrase as a kind of cliché without actually thinking through its import. Because there really is a “Black vote,” even though Black voters are, like all people, diverse in their specific opinions. Years of Democratic Party thinking was based on the idea that there would be a “Latino vote” that could and should be courted in an analogous manner. There was a heavy emphasis on turnout rather than persuasion, identity-based appeals, and most of all, a belief that you could blow off specific analysis of ideological self-identification and issue positions at low cost.

The new conventional wisdom

If you want some good takes on where things stand, I’d recommend this Pablo Manríquez article, as well as Miriam Jordan’s piece on racism in Latin America and in Latin-derived communities in the United States. I’d recommend Jay Caspian Kang on the difference between ethnic politics grounded in community solidarity and ideological anti-racism. And I really recommend “Reversion to the Mean, or Their Version of the Dream: An Analysis of the Latino Voting in 2020” by Bernard Fraga, Yamil Velez, and Emily West which concludes the rightward shift in the Hispanic vote may be permanent. I also recommend Ruy Teixeira’s article “Hispanic Voters are Normie Voters.”

This new conventional wisdom is, I think, completely correct — Americans of Latin American ancestry are a very diverse group with a range of ethnic backgrounds, issue positions, interests, etc.

This has always been personally salient because my grandfather was a Cuban-American leftist whose family came to the United States before the Cuban Revolution. He had very little in common politically with the mainstream Cuban-American community in the United States, which was dominated by anti-Castro emigrés. Which is just to say that even though everyone always knew the Cuban-American case was somewhat “special” in political terms, I knew that amongst Cuban-Americans, there were a lot of differences based on specific family experiences and, ultimately, the individual ideas of individual people.

And I think it’s important to remember the extent to which this was not the conventional wisdom in the recent past.

Teixeira, famously, was the author of “The Emerging Democratic Majority,” a book whose actual thesis was more complicated than the caricature, but that a lot of people read as “the growing Hispanic population will deliver victory to the Democrats.” Fraga wrote the more recent book, “The Turnout Gap: Race, Ethnicity, and Political Inequality in a Diversifying America.” His newer work doesn’t contradict anything the older work on turnout says. But it does reflect an important shift in emphasis from a mobilization frame to a persuasive one.

I’ve written about this a couple of times, but understanding the depth and persistence of the belief that Democrats could win elections through mobilization alone is critical to understanding what’s happened over the past decade of American politics. A lot of progressives were very disappointed by Barack Obama’s eight years in office. As far back as 2011, Jonathan Chait was writing pieces about how progressives are disappointed by every president and should maybe alter their expectations. But most progressives didn’t agree with that and wanted to construct a theory of how it would be possible to run and win campaigns with a much more progressive agenda.

If you want to understand why Democrats moved left on almost every issue since 2012, this misread of the Hispanic vote is a key piece of the picture. The idea was that if the party went left on criminal justice issues, Black turnout would remain high. Then the party could go left on immigration to maintain high Hispanic turnout, and count on the rising Hispanic share of the population to loft Democrats to victory as they moved left on climate and economics. The belated recognition that there are lots of moderate and conservative Hispanic voters, that the conservative ones will probably vote Republican, and that you need to court the moderate ones by paying attention to what they actually think and care about is welcome. But I think assimilating the significance of those facts requires revisiting some earlier debates.

Politics for an era of racial depolarization

Among other things, I think the failure of the analogy between Hispanic voters and Black ones calls for some reexamination of the conventional wisdom about Black voters.

The Trump Era generated a lot of takes on what Ezra Klein called “White Threat in a Browning America.” And I do think it’s clear that the politics of white threat were a real issue during this period. At the same time, it’s striking that not only did Trump do better with Hispanic voters in 2020 than Mitt Romney did in 2012, but he also posted some modest gains with Black voters. To some extent that’s probably just a question of whether Obama is on the ballot. But looking at the polling in Georgia, I think it’s pretty clear that there are some African American voters who are picking Raphael Warnock over Herschel Walker and Brian Kemp over Stacy Abrams. I don’t think I’d say that’s necessarily because of a huge ideological divide between Warnock and Abrams. But Abrams has the misfortunate of needing to run against a pretty strong opponent while Warnock has a weak one. And that matters.

“Candidate quality matters to Black voters’ decision about who to vote for” is not exactly an earth-shattering revelation. But it’s a reminder that while average behavior is very different across demographic groups, at the margin people are pretty similar.

More broadly, politics in practice is getting less racially polarized even though progressives are talking about race and racism more. The average educational level of the population is rising, so people are becoming somewhat more sophisticated about politics and ideology. And the country is becoming more diverse and more integrated — intermarriage rates are rising, for example — while church attendance is falling. Educated white people have developed a lot of progressive opinions about race, while the power of distinctive social institutions like the Black church has fallen. So actual voting behavior is coming to be more driven by individualized opinions and less by broad identity considerations.

Over the course of October, I’ve seen a lot of dark humor from progressives about voters who care more about gasoline prices than about the future of democracy. And there is something short-sighted about that.

At the same time, voters making their decisions based on material self-interest is what progressives spent most of the past 50 years wishing would happen — and it just is the case factually that the prices of energy and agricultural commodities are important parts of material self-interest. Everyone buys food and almost everyone buys gasoline. People also care about the price of prescription drugs (where Democrats have a great message this year) and housing and other things. They care about the quality of their schools. Giving up on the dream of demographics as destiny is hard, but in a lot of ways, this is just politics as it should be.

My anecdotal experience is that Hispanics are following the same path as past waves of Catholic immigrants. I come from a large-ish family originating in those waves in the late 19th and early 20th century. In the last 10-12 years we have incorporated some Hispanic (mostly Salvadoran) limbs. The other families I know like mine are also experiencing this, with so and so's sister or brother or cousin marrying a 2nd generation Hispanic. Based on this trajectory I think in a couple decades thinking about Hispanics as an insular minority will be as outdated as the doing the same with Irish or Italians. Sure people will be proud of their heritage (which will be more and more mixed) and there will be a few cultural hand me downs but it won't be a major factor in how people vote.

And all of this is a good thing. It's the path from starting out in a Democratic machine when people arrive to becoming fully assimilated, individualistic Americans. Democratic strategy should be forward looking about this process, instead of doing the ethnic-identitarian pigeonholing.

As a recovering addict myself, I feel confident in asserting that Dems continue to be addicted to the high of moral superiority that comes with feeling confident your political opponents are drowning in their own racism. This creates a major blind spot where the only reason for supporting an R policy/opposing a D one is due to one’s racism/white supremacy. Of course this leaves one shocked if one goes to the effort of learning why a Latino voter might be uneasy with talk of open borders. What’s fascinating is that, when you look by racial group, Pew shows each group considers their racial identity to be of hugely different importance to their sense of self. Black people, and by extent Black voters, center their own “blackness” in their self-perception to a greater extent than do Latinos their Latinoness and a MUCH greater extent than whites. (Whites of all political backgrounds tend to have a taboo against building a sense of identity in their whiteness, for excellent reasons!!). It is perfectly logical that the more you center your racial identity in your sense of self, the more you see the actions of others through that lens.