The case against legal gambling

The costs of addiction aren't worth a little extra tax revenue

This piece is written by Milan the Intern, not the usual Matt-post.

Until recently, I hadn’t given legalizing gambling much thought. My view was that people betting on the Super Bowl were mostly having some harmless fun and were going to do it anyways under the table, so we might as well legalize it and get a cut of that money for schools and whatnot. I even placed a few small bets on campaign outcomes.

But three New York Times articles challenged my thinking. First, I read two opinion pieces — one by Ross Douthat and another by Jay Caspian Kang — which argued that the costs of America’s move to legalize sports betting are exceeding the benefits. Then I read this profile of a man named Steven Delaney documenting his struggle to recover from gambling addiction and the toll it took on him and his family.

After looking at the evidence, I think Kang and Douthat have it right.

A brief history of gambling in America

In 1931, Nevada legalized most forms of gambling as a measure to boost the economy during the Great Depression. Then in 1964 New Hampshire created the first state lottery, followed by New York and New Jersey. Today, 45 states and D.C. run lotteries.

Later, in California v. Cabazon Band (1987), the Supreme Court held that state and local governments did not have the authority to regulate gambling on Native American reservations. In 1988, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act which set up the Native American gaming industry.

The most recent development is the rise of online sports betting after the Court overturned a 1992 federal law that effectively banned sports betting in most states in Murphy v. NCAA (2018). These days Americans are betting billions every month.

Timothy O’Brien and Elaine He at Bloomberg found that the value of bets placed on sports games increased twenty-fold from 2018 to 2021, driven mostly by growth in bets placed on mobile devices. Goldman Sachs has predicted that online sports betting could generate $33 billion in revenue by 2033, compared to less than $1 billion in 2021. Gambling is big business.

Entertainment or ignorance?

One of the things I learned watching Jonathan Gruber’s microeconomics lectures is that people are generally risk-averse.

Imagine someone offers you a wager on a coin toss: heads you win $120, tails you lose $100. That’s a more than fair bet. The “expected value” — the probability of winning times the amount you win — is $10. But you probably wouldn’t take it because winning $120 won’t feel as good as losing $100 will feel bad.

Which raises the question — why do people gamble at all?

After all, there’s a reason people say that “the house always wins” — most wagers offered in casinos are less than fair by design (otherwise, the casino wouldn’t make money).

Well, Gruber says there are basically two schools of thought here:

Consumers could be rational — fully aware of the unfavorable odds but deriving entertainment value from the thrill of betting.

On the other hand, consumers could be ignorant — not understanding that they’re very unlikely to win and wasting money on false hopes.

There are certainly some people who fit either description, but which explanation is generally true has critical and opposite implications for public policy.

The case for legal gambling assumes that consumers are mostly rational. If so, legalizing gambling would have positive effects — people would move from illegal gambling to the legal market (depriving criminal organizations of money) while voluntarily contributing tax revenue that can be spent on public services and supporting new businesses and jobs in exchange for clean entertainment. Gambling is like alcohol — most people who partake do so responsibly and in moderation, and they should be allowed to enjoy themselves.

But if consumers are mostly irrational, then legalization is a bad idea. Opponents of gambling argue that many consumers become addicted and can end up losing their livelihoods. Addicts might cut back on spending on their families to feed their habits, and the state would have a perverse incentive to increase (or at least not reduce) addiction in order to increase revenue. Less-educated people could be less likely to understand that the odds are stacked against them, so gambling might function as a tax on the poor.

So what we want to know is whether consumers are rational, whether gambling is addictive, and more broadly speaking, who the winners and losers of legalization are.

Consumers are (at least partially) rational

We can’t peer inside the minds of consumers as they buy lottery tickets, but we can still get an idea of how rational they are by looking at how they respond to bets with different expected values. And studying whether legalization reduces illegal gambling consumption is fairly easy.

In a 2002 paper, Melissa Kearney looks at consumer behavior and finds that legalization does not cause people to shift from illegal to legal gambling — people instead reduce non-gambling consumption to increase spending on gambling — and that people spend more on gambling in states with lotteries than in those without. The distributional impact of gambling is also somewhat regressive:

…average annual lottery spending in dollar amounts is roughly equal across the lowest, middle, and highest income groups. Reported annual expenditures are $125, $113, and $145, respectively. This implies that on average, low-income households spend a larger percentage of their wealth on lottery tickets than other households.

But controlling for other characteristics, sales of lottery tickets are positively driven by the expected value of the wager. In other words, consumers are at least somewhat rational — they’re more likely to buy lottery tickets with more favorable bets.

Addiction and the whale hypothesis

In different 2002 paper, Kearney tried to figure out whether the lottery was addictive by looking at “lucky stores” in Texas — the phenomenon of lottery sales increasing when a store sells a winning ticket due to people believing that “lightning will strike twice.” This is a nice natural experiment since which store will sell the winning ticket is essentially random, so you get exogenous sales booms and you can look and see if the increase in sales persists, which might indicate addiction. Unfortunately, Kearney wasn’t able to get conclusive results on addictiveness in the 2002 paper.

A newer study she did with Jonathan Guryan in 2009 looked at the same phenomenon with better data and finds that the week after a winning ticket is sold in a ZIP code, ticket sales are 14 percent higher than in non-winning ZIP codes (38 percent higher at the winning store itself, 5 percent at other stores in the winning ZIP code). After six to 12 months, roughly half of the initial increase in consumption is maintained, and after 17 months, roughly 40 percent of the increase is maintained.

If one assumes that the lucky store effect wears off after a while (and mostly applies to the winning store itself) then it seems likely that some of this long-term increase in consumption reflects people starting to play the lottery during the initial shock and then getting hooked.

Free-to-play mobile games like Candy Crush make the majority of their revenue from “whales” — the small minority of users who spend what are probably unhealthy amounts of time and money on the game. The top 10 percent of drinkers make up more than half of all alcohol consumed in America in a given year — that’s 74 drinks per week — which is definitely unhealthy. The same appears true for gambling. According to an investigation by the Wall Street Journal, among the top 10 percent of bettors in a casino, 95 percent ended up losing money, with those among this group who lost more than $5,000 outnumbering those who won more than $5,000 by 128 to 1. The casino earned more than half its revenue off of the top 2.8 percent of losers, with the top 10.7 percent providing 80 percent of revenue.

A mixed blessing

In her aptly titled 2005 study “The Economic Winners and Losers of Legalized Gambling,” Professor Kearney looks at three types of betting: casinos, state lotteries, and online gambling.

She finds that Native American casinos are likely a net positive for tribes due to the increase in economic activity they generate, while riverboat casinos don’t really boost the local economy (people mostly come just to gamble and don’t patronize other local businesses). Casinos have negative social effects on the surrounding area — such as more crime and addiction — but due to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Cabazon Band, state governments cannot force Native American casinos to internalize these social costs via corrective taxation.

Kearney finds that Black people spend nearly twice as much on the lottery as white or Hispanic consumers, and reiterates the finding from her 2002 paper that low-income households spend a higher share of their income on lotteries. Poorer consumers tend to favor “instant games” such as scratch-off tickets, which are especially risky for addicts but also very lucrative for states. In states with lotteries, households in the lowest third of the income distribution “demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in expenditures on food eaten in the home (2.8 percent) and on home mortgage, rent, and other bills (5.8 percent).”

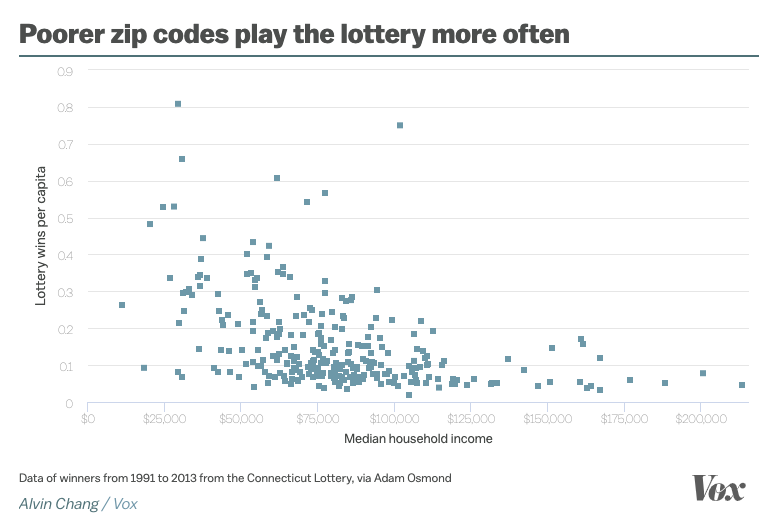

In a 2016 Vox article, Alvin Chang looked at data from the Connecticut lottery and found that the per capita consumption of lottery tickets was higher in poorer neighborhoods.

According to Kearney, lottery proceeds made up a relatively small share of state revenues in 2005, ranging from 0.28 percent in Montana to 8.27 percent in Delaware. Here is a chart that I made using data from 2019 for a more up-to-date picture.

But how is this money spent? Well, Kearney finds that one dollar from lottery revenue earmarked for education leads to an additional 60 to 80 cents in K-12 spending, while states that place lottery money in the general fund only increase K-12 spending by 40 to 50 cents on the dollar, and states that put the money somewhere else increase school spending by only 30 cents.

The paper doesn’t have as much to say about Internet gambling (which at the time was fairly new) but notes that it is rapidly growing and harder to regulate, with distributional impacts and consumption effects being unclear. But it seems reasonable to assume that it can also become addictive and that addicts provide most of the revenue.

It’s probably too late to go back on legalization

To recap, the literature finds that neither advocates nor opponents of legal gambling are entirely correct.

Most consumers are at least partially rational, but some people can and do become addicted and the industry seems to depend on those people to turn a profit. Legalization increases gambling consumption at the expense of reducing non-gambling consumption but does not lead people to switch from illegal to legal betting. Native American tribes really do benefit from being allowed to run casinos, and lottery money being earmarked for education does increase spending on K-12, but as a tax, gambling is regressive.

Now in some sense, the cat is out of the bag. Online betting websites and cryptocurrencies make it much easier for consumers to evade their local regulations. Post-Murphy, every state has an incentive to legalize gambling once its neighbors do so as to not lose out on tax revenue.

A large majority of voters believe that gambling is morally acceptable and polling generally indicates that voters support legalization. The industry has racked up wins at the ballot box — measures greenlighting sports betting easily passed in Lousiana, Maryland, and South Dakota in 2020.

Barring any major changes in public opinion or case law, it seems likely that legal gambling will continue to spread. But I think that’s a net negative for society.

Legal gambling has diffuse benefits and concentrated costs. The classic example of a policy with these characteristics is free trade — consumers benefit a bit from cheaper goods, but workers who lose their jobs to outsourcing take a really big hit, even if in aggregate the benefit to consumers is greater. In theory, at least, we can make free trade a positive development for everyone by taxing the winners to compensate the losers — such as paying for job-retraining programs with a consumption tax.

But with gambling, we can’t really compensate the losers. It doesn’t make much sense to collect a bunch of tax revenue from people with gambling problems and then spend some of it on anti-addiction programs — we’d be better off just not taking the money in the first place. As you can see from the 2019 data, it’s not like lottery revenue is a huge share of tax collections for any state, and if we want to increase education funding we can raise taxes on the wealthy. The small entertainment benefit to responsible consumers and the extra tax money just don’t seem worth the huge hit to people who become addicted.

Now, you could make many of the same arguments about addiction, diffuse benefits, and concentrated costs with regard to legal marijuana. I admit that I might be biased here — candidly speaking, I’m personally more likely to use cannabis than go to a casino. But the crucial difference to me is that young people are substituting marijuana for alcohol which is an improvement on balance for public health. But people are just increasing their overall gambling consumption in legal states rather than substituting illegal betting for legal betting, which increases the number of people who become addicted and the negative social costs thereof.

The setting for the finding that legalized gambling doesn’t reduce illegal gambling is the lottery. The current setting is legalized SPORTS betting. It seems much more plausible to me that legalized sports betting will reduce illegal sports betting in a much more significant way. “More plausible to me” is not the same thing as “true,” of course, but much of your argument seems to rest on the lack of illegal-to-legal substitution. I think there are good reasons to question whether the lottery finding is generalizeable to other types of gambling.

Milan, I genuinely applaud your willingness to put your ideas out here to the SB crowd, even if they give you crap about them.