Should the bus be free?

In most cases, the better investment is to make the buses better

Every so often someone asks me what I think of making the bus free as a way to encourage transit ridership. I then tend to disappoint them with an extremely long-winded answer, but in a nutshell: it’s complicated.

In a very abstract way, free transit makes sense. Cars generate pollution and traffic externalities. Ideally, we would fully price those externalities with a carbon tax and congestion charges. But in the real world, both are politically difficult, so an equivalent way of addressing the issue would be to subsidize the low-externality option — the bus — by making it free.

But this is a somewhat awkward structure of argument. The ideal plan is to price the externalities. The free bus is supposed to be the second-best, “it works in practice” fallback option. But does it work in practice? With the exception of cities with extremely low ridership where transit policy is therefore relatively unimportant (I once rode the bus in Tulsa, and it was both infrequent and extremely uncrowded), you generally have to assume the availability of a large pot of money for your transit agency to replace the fares you’re eliminating.

So then the question becomes: if you assume your transit agency has a bunch of extra money, is eliminating fares the best way to turn money into ridership?

Bus riders want better buses, not cheaper

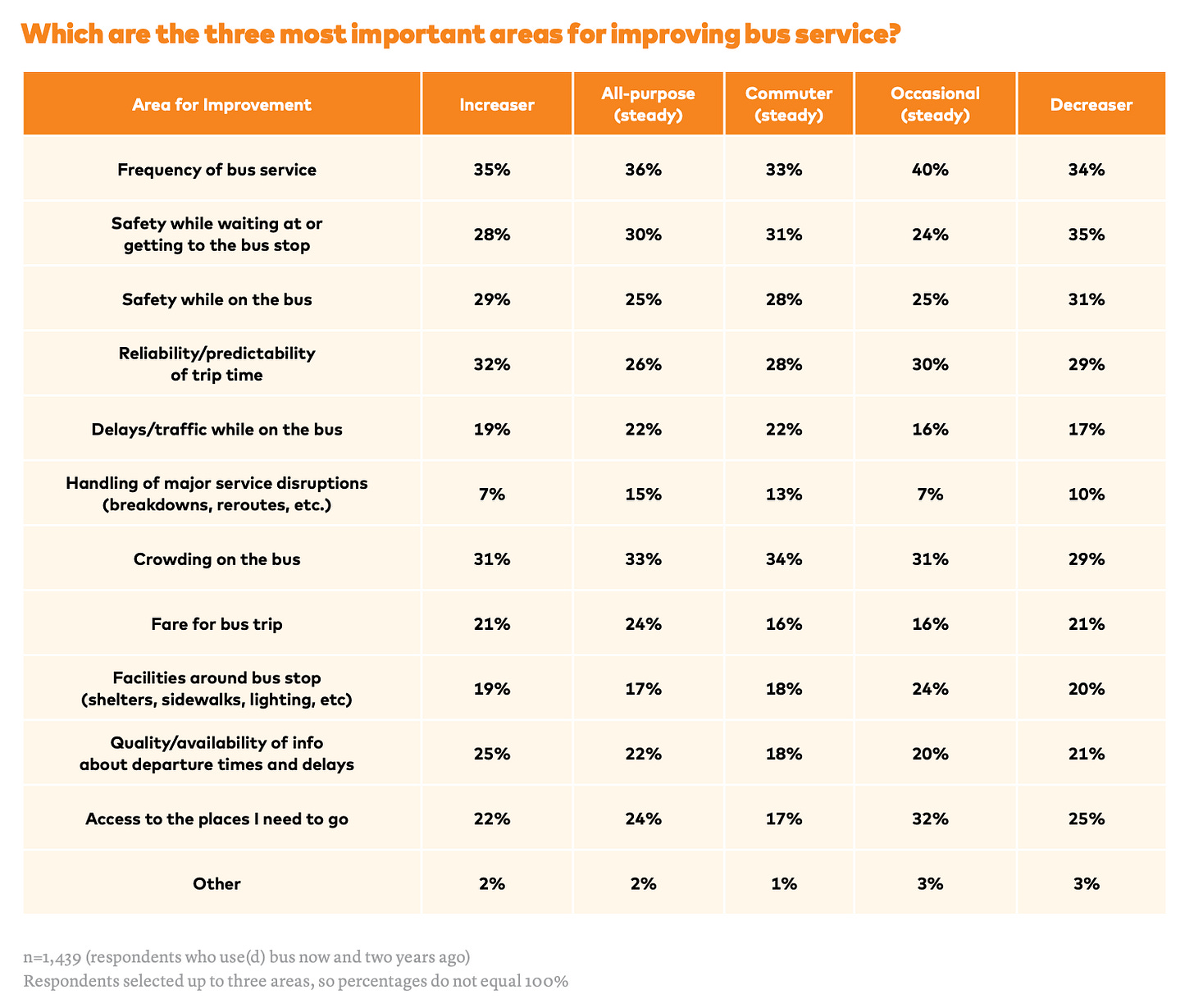

Back in 2019, Transit Center published a poll of bus riders asking respondents why they were reducing transit usage pre-pandemic (the answer, basically, is that an improving economy allowed more low-income people to afford cars) and what their priorities are for making the bus better. They broke the riding population down into five categories: those who increased bus usage, those who decreased it, and three groups of riders whose use did not change, including occasional bus riders (that’s me), regular bus commuters, and those who use the bus for all-purpose transportation.

The main takeaway is that cutting fares is a relatively low priority compared to other things you can straightforwardly achieve with more money, like improving bus frequency and reducing bus crowding.

Investing in cheaper fares just barely beats investing in better bus stop facilities as a priority. And I think it is pretty clearly dominated by running more buses, which would address both frequency and bus crowding concerns.

Certainly, as an occasional rider, that’s my perception. When I’m traveling to a destination that’s served by the bus lines that run on 14th Street in D.C., I typically take the bus. That’s less true of the lines that run on 11th Street because the bus is so much more infrequent. And of course, I don’t take the bus to destinations that aren’t on a route that’s convenient to me. This, I think, is a pretty normal set of priorities — transit is good when it’s convenient, but not when it’s not.

I’m pretty rich, but Transit Center reports that “even low-income bus riders rate fares as less important to address than frequency of service, crowding, safety, and reliability.”

It’s worth noting that there is regional variation in rider priorities. Bus riders in Los Angeles and Chicago had a lot of concerns about safety, while those in other cities did not. Riders in Denver were much more likely than riders elsewhere to cite concerns about fares, so maybe Denver specifically should look at lower fares. But even there, the fundamentals were a bigger concern.

Long story short, I think governments should be willing to spend more money on their bus systems. But rather than mandating lower fares, politicians should give the agencies a clear mandate to increase ridership, and agencies should then pursue that mandate in technically rigorous ways. And that probably means frequent service on high-demand routes — achieved, if necessary, by eliminating other routes — rather than investments in fare cuts.

The other way to lower fares

There isn’t a ton of research that looks at the impact of reducing bus fares, but in a 2017 article for The Journal of Public Economics, Rhiannon Jerch, Matthew E. Kahn, and Shanjun Li calculated that the increased transit ridership induced by a 30% across-the-board reduction in bus fares (made possible by reducing bus driver pay through privatization) would “lead to a gain in social welfare of $524 million, at minimum.”

They start with the observation that across America’s top 20 cities, there are huge gaps in the cost per mile of providing bus service. This is in part because the bus drivers get paid different amounts, largely because of different union contracts in different places. But there are also generally non-union, private sector bus drivers all across the United States. So, Jerch, Kahn, and Li looked at what would happen if you privatized all the transit bus systems, busted the unions, and paid a market-clearing wage.

Their answer is that “fully privatizing all bus transit would generate cost savings of approximately $5.7 billion, or 30% of total U.S. bus transit operating expenses,” and that’s what would generate the social welfare benefits in terms of higher ridership.

The upside to cutting fares by cutting costs, of course, is that instead of having spent a bunch of money to reduce fares, you reduced fares essentially “for free” and can still make new public investments.

When considering this proposal, though, I do think it’s important to really hear what they are saying. I first saw this article years ago thanks to Tyler Cowen, who wrote it up as “we should do more to privatize bus systems.” If you’ve ever been to a major European city, you might be interested to know that across the pond it’s very typical to have privatized transit operations. An urban transit agency in Europe typically acts as a regulator and, to an extent, a payor of bus companies, but it does not own buses or employ bus drivers. This is an interesting philosophical difference about how to think about managing public services. But if you think about privatized bus operations in Denmark, you’re still talking about Denmark with strong unions and collective bargaining in all sectors of the economy. It’s a management tweak.

The Jerch/Kahn/Li paper is not really saying the private companies bring some magic new efficiency to the bus task, just that, in the American context, you can normally replace unionized workers with non-union workers who you pay less by contracting out your public service. It sounds a lot less high-minded that way, but it does potentially work.

Land use is everything

But ultimately, the most important factor in transit ridership is land use.

One thing the Transit Center document revealed was that many low-income riders had stopped using transit because rising rents pushed them out of the transit-rich neighborhoods. This is the exact same problem with improving urban public schools or any service. Lower-income people are more likely to use public services and more likely to benefit from improved public services, but not if the improvements just cycle back in the form of higher rent. You need to be able to actually add more housing in the locations that have become more desirable due to improved services.

But land use is especially important to transit. The most obvious reason for that is density. When you spend a bunch of money building a metro system, but don’t rezone for dense housing near the stations (looking at you, Los Angeles), you don’t get any riders. I mentioned the appealingly high frequency on the 14th Street buses in D.C., but the reason it makes sense to run buses frequently is that 14th Street passes through some of D.C.’s densest neighborhoods, so there are plenty of potential passengers.

If you look at places where transit ridership is high, it’s not that the fares are unusually low, but that there is density and quality service. Parking in Midtown Manhattan is an expensive hassle, so normal people from all walks of life prefer to take the subway. It’s not like the whole country will or should become as dense as Manhattan. But everywhere you look, regulations are in place to curb density, often in places where local elected officials claim they want to encourage transit usage.

More transit for whom?

The appeal of free transit comes, to an extent, from a bad mentality lurking in the subtext of transit discussion in a lot of American cities: the belief that someone else should ride mass transit. Many of the people involved in these discussions want to keep living their lives exactly the way they are, except with less pollution and traffic congestion, so it would be good for other (poorer) people to ride the bus. Free transit fits that frame very well.

But if you start talking about making transit objectively and broadly more appealing to ride, you’re talking about making the bus run faster, perhaps with bus lanes or signal priority. You’re talking about reducing stop frequency even if it annoys a few people. And you’re talking about improving bus frequency. These are things that might make you take the bus.

You’re also talking about reforming land use. Imagine going from Point A to Point B, except now parking at Point B is more expensive and also slower in your car because road space has been given over to dedicated bus lanes. But not only are the buses faster, but they’re also more frequent. Well, you might take the bus now. And so might other people, because other people are also like you and care primarily about the relative convenience of driving versus riding the bus.

But that’s not what you wanted. What you wanted were policy changes to make other people take the bus so that your drive would get even faster and more convenient. Making the bus free fits the bill; it doesn’t impact your life at all. But most people are people like you, so the actual impact on ridership or on your city is going to be minimal.

It will help some very poor people save some money. But if you want to give them money, you could honestly just give them money, and they could use it for bus fare or whatever else they need. Like a lot of half-baked ideas, it’s sort of caught betwixt and between an idea for improving public services and an idea for redistributing income, and it doesn’t make a ton of sense as either.

In SF, where we literally never enforce bus (muni) fares, our favorite limousine socialist, Dean Preston, is trying to run on "free muni". It's not like they want it to be better. They just want something to campaign on.

The only thing that would make muni better is to privatize it and let Google run it. They already run a much nicer fleet of buses here, which get egged by the anti-tech crowd for being "too nice" and "too convenient allowing the workforce here to freely and easily get to work". Dollars to donuts, if you deregulated them, they'd have them self driving, with high speed wifi and Kombucha on tap before the end of the year.

Meanwhile, muni and SF city government spends 6 years painting the center lane of van ness red to make a bus lane.

I am a die hard democrat, but city governance for infrastructure... I can see how people like Bloomberg get elected to fix messes like this.

Writing from a bus in Phoenix here. Homeless folks on free or lightly regulated public transportation are a major roadblock to commuter bus use. I am pro public services for homeless, yet riding the bus all day for free air conditioning is not optional. That's the top comment I hear from peers when people hear I commute on public transportation. There are also crowding and safety concerns with perpetual riders.

Increasing the fare is a useful gate keeping mechanism. The policy on Phoenix is generally fare optional as bus drivers are trained not to force the issue with non paying riders. I'd much prefer some enforcement and more investment in addressing homelessness directly (more homes).