Donald Trump stepped back from the brink of his Liberation Day tariff insanity. But even in rolled-back form, he’s still pushing taxes on imports up to the highest levels in American history. In fact, I think the sheer insanity of the “reciprocal tariffs” has obscured exactly how radical the policy Trump landed on — ten percent across the board tariffs, plus higher tariffs on Canada and Mexico, plus gargantuan tariffs of over 100 percent on China — actually is.

On the campaign trail, Trump took a lot of criticism (including from Slow Boring) on his promise of a 10 percent global tariff. His allies on Wall Street — people like Scott Bessent — kept reassuring the business community that Trump wouldn’t actually do this. The shock of Liberation Day was that rather than rolling out something more modest than the insane 10 percent plan, he rolled out something more radical. Now it’s been scaled back, but the administration’s policymaking is still in the grips of the bizarre idea that large taxes on all imports are a good idea.

Reflecting on weeks of arguments over tariffs, it occurs to me that the specifics of this policy (and other bad Trump trade policies) are grounded in a larger set of myths around trade, and specifically trade deficits, that extend beyond Trump. And many of these myths circulate on the left as well as the right.

So today I want to break down four big things that many people get wrong about trade deficits: bilateral deficits don’t reflect trade barriers, global trade deficits aren’t bad, free trade does not primarily benefit rich people, and reducing imports is not the key to bolstering manufacturing. A lot of people seem to find it annoying that economists are so uniformly opposed to tariffs, as if it proves there must be some conspiracy among the profession. But economists disagree about lots of stuff. The unanimity on tariffs reflects the fact that a lot of people just wildly misunderstand the basic facts about trade balances.

Myth 1: Bilateral trade deficits reflect trade barriers

“The trade deficit” is America’s exports minus its imports, and it’s a worldwide figure.

You can break it down into specific pieces, though — America’s exports to Canada minus its imports from Canada is our bilateral trade deficit with Canada.

When Trump talked about “reciprocal tariffs,” it sounded like he was saying we should levy the same tariff on foreign countries’ exports that they put on our exports. I don’t think that’s a very good idea, but at least I can follow the logic of it. That’s not actually what he did, though. What he did was calculate a tariff rate for each country based on that country’s bilateral trade surplus with the United States. His administration asserted that they were trying to account for the presence of non-tariff barriers to trade.

Non-tariff trade barriers are real, but the idea that you can estimate their impact from bilateral deficits is nonsense.

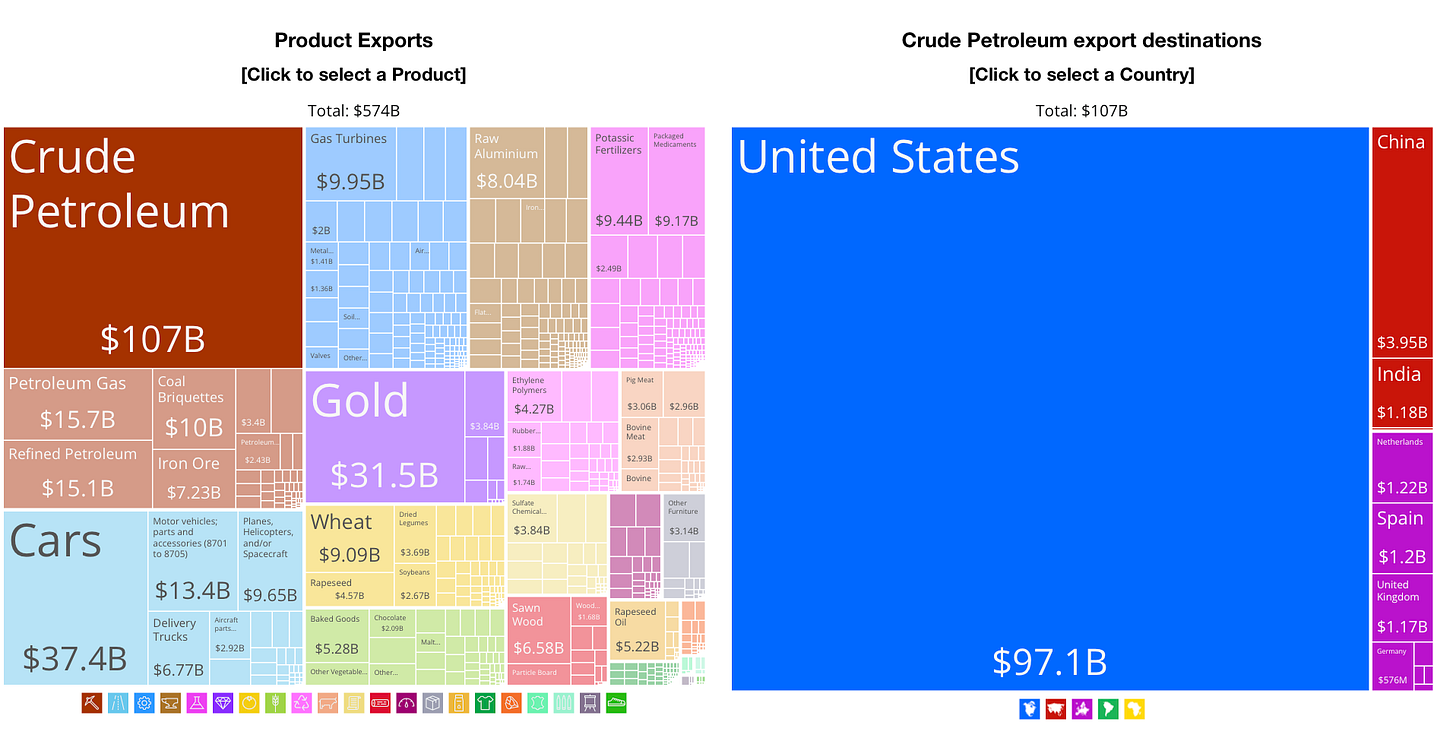

Canada’s single largest export is crude oil, because Canada has a robust oil industry and a low population. Canada exports a ton of crude oil to the United States because the logistics of shipping Canadian oil to American refineries are much easier than the logistics of shipping it elsewhere. The United States is also Canada’s number one source of inputs, because of course we are — we’re a gigantic country right next door! But Canada also imports a lot from other major world economies, like China, Japan, Germany, and South Korea. Canada does not export very much oil to those countries, because they’re far away and it’s easier to ship the oil to the closest country. As a result, Canada runs a trade surplus with the United States and a deficit with these other countries. This has absolutely nothing to do with trade barriers between the United States and Canada — Canada imports four times as much from the United States as they do from China — it’s just that these Canadian oil exports very overwhelmingly go to the United States.

A fun fact about the United States is that we are actually a significant net exporter of oil. We could stop importing Canadian crude, build new infrastructure to route oil from Texas to the refineries that are currently supplied with Canadian crude, and retool all those refineries to be suited for Texas oil instead. If we did that, the bilateral trade deficit with Canada would be slashed, possibly even eliminated.

But it would be expensive and also pointless, because every barrel of oil we avoid importing from Canada would just be a barrel that we failed to export elsewhere. The logic of the oil trade is driven by geography, infrastructure, and the legacy of which refineries are built to do what. Estonia imports more from Lithuania than from Latvia, but exports more to Latvia than to Lithuania. Why? I don’t know. It looks like Estonia specifically exports electricity to Latvia but not to Lithuania — presumably because Estonia borders Latvia but not Lithuania. These things just happen and have nothing to do with trade barriers.

Myth 2: A trade deficit is bad

It is definitely good for a country to have successful export industries. But having successful export industries is not the same thing as running a trade surplus.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.