Fictional politics as a vocation

Plus Mamdani vs the establishment and the Free Press’s hustle

Before we get to this week’s answers, I wanted to acknowledge that we got a bunch of good questions about immigration, both forward-looking and backward-looking, in the mailbag. I didn’t answer any of them, because I was working on part one of what will be a multi-part immigration series looking back on how we got here and what might work going forward.

So please know that I’m not ignoring you; I’m just trying to work my way through my thoughts on this systematically. Obviously a lot of attention right now is on short-term tactical responses to things that Trump is doing in real time, and that’s important. But I kind of want to step back from commenting too much on it and focus instead on laying the groundwork for understanding the issue on some deeper levels.

Sasha Gusev: Political films seem to mostly fall into two tracks: the ideologically pure protagonist is corrupted by politics or always was (The Candidate, The Ides of March, A Face in the Crowd, Primary Colors, Wag The Dog, In The Loop), or the ideologically pure protagonist stands on his principles and wins (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The American President). Is there any film (or other work of fiction — but no biopics!) that actually elevates political moderation as both difficult and meritorious, rather than treating it as “selling out”?

The “no biopics” rule makes this very hard in a way that I think is telling.

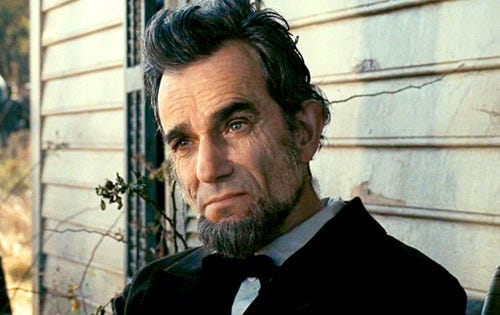

I rewatched Steven Spielberg’s late-career masterpiece “Lincoln” recently, and it’s hard to think of a better cinematic depiction of the slow boring of hard boards. I remember that, upon release, it was widely read as a kind of apologia for Barack Obama in the face of leftists’ anger that he hadn’t unleashed revolutionary change in his first term.

But the more distance you get from the circumstances of 2012, the less that immediately comes to mind and the more it reads as a broad depiction of successful progressive politics. You could apply it to Obama, but you could apply it equally well to F.D.R. or anyone else who enacted major change but also was in practice constantly compromising. The 2008 Gus Van Sant biopic “Milk” leans more into idealism, since part of the story is Harvey Milk challenging San Francisco’s gay establishment, which is afraid of rocking the boat. Still, because it is telling the story of an actual politician, it shows you that Milk ends up having productive interpersonal relationships with people who hate him, builds alliances with people who don’t share all of his ideas, and also has to deal with the humdrum aspects of municipal government. I don’t think the HBO movie “All The Way” about Lyndon Johnson or the Netflix Bayard Rustin biopic were as good as those two, but they do also — by depicting people who actually accomplished things in politics — move us beyond the tropes identified in the question.

I think the tellers of fictional stories struggle a little bit with this for a few different reasons. One is that there is a kind of temperamental horseshoe between the avant-garde sensibilities of artists and the normie audience preference for black-and-white morality stories. But another is that, especially when you’re talking about making a movie, you need to think about what you’re actually going to put on screen.

“Lincoln” is a strange movie in the sense that it’s full of scenes that are just guys in costumes having meetings. Political leadership does, in fact, consist largely of having meetings. If you have five Best Director nominations under your belt, plus an insane roster of blockbusters, you can get weird ideas financed. But even so, the fact that it is about Abraham Lincoln, an extremely famous historical figure, is part of why it works. A made-up story about made-up guys having meetings about legislative negotiations is a really hard slog. A political movie that I like, “The Contender,” decides to slip at the last minute into gale force idealism by having Jeff Bridges deliver a rousing oration to a joint session of Congress. This does not make a lick of sense as a depiction of the American political system — just ratcheting up the polarization on this issue is not going to accomplish anything. But the big set-piece speech is the American presidency at its most cinematic, and part of what you’re trying to do with a movie is have cool scenes.

Some of these stories, though, have to be read a bit against the grain.

The Tommy Carcetti character in “The Wire” is an unflattering portrayal of a young up-and-coming politician. But the specific calls he makes largely seem correct to me.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.