Fancy stations make quality mass transit harder

Stop wasting money in dumb, obvious ways

I’ve been writing sporadically about America’s sky-high mass transit construction costs problem for years now, largely piggybacking off the work of Alon Levy who started cataloging this as an enthusiastic amateur and now has been able to get into mass transit analysis professionally. More recently Eric Goldwyn at NYU’s Marron Institute of Urban Management has been able to get funding to work with Alon on a big Transit Costs Project that they hope will get to the bottom of exactly what’s going on.

They recently produced their first big case study on Boston’s Green Line Extension and it’s a fascinating document with a bunch of different things going on.

It’s actually disappointingly clear from reading just one case that there isn’t going to turn out to be a single simple solution like we’ve gotta change this one contracting practice or there’s this one bad thing the unions are doing. The whole undertaking is dysfunctional in a very multi-faceted way.

But their research also revealed something almost comically simple. In the original plan for the Green Line Extension (GLX), the idea was to make the stations basically the same as the existing stations on Green Line surface stops. But then somehow as the project got underway, the station plans got much more elaborate and started calling for drastically larger structures that cost enormously more to build. Eventually, the whole thing was getting so expensive that it was going to be canceled. Then as part of getting GLX rebooted, they went back to the original plan for cheap stations.

Again, to be clear, these weren’t expensive stations because of some complicated corruption. It was just literally they decided to build huge fancy stations instead of simple cheap ones (arguably a simple form of corruption). Then when external actors put their feet down and demanded cheaper stations, the stations got cheaper. The whole thing is just stupid.

The Green Line context

I hosted an online event with Eric and Alon and their colleague Elif Ensari during which it became clear to me that not everyone has actually ridden the Green Line and thus lacks the context for exactly how bizarre the MBTA’s conduct was here.

So to back up, Boston has a four-line subway system that people call the T.

Of the four lines, three of them — the Red, Orange, and Blue — are classic heavy rail metro lines. The fourth (but oldest) the Green Line is a bit weird. It runs much smaller light rail vehicles like you see in a lot of streetcar systems. But in downtown Boston, the streetcars run in a subway tunnel from Lechmere to Copley Square. Then at Copley, it starts branching, and the branches run as streetcars on the surface. But good streetcars with dedicated lanes. Not terrible mixed-traffic streetcars.

Still, on the surface branches, a streetcar running in a dedicated lane is not all that different from a bus running in a bus lane. The stations, consequently, are like glorified bus stops.

Here’s Coolidge Corner, which is sort of the “downtown” of the suburb of Brookline:

Here at Brookline Hills in a more suburban-y part of the suburbs there’s a little hut for the parking lot along with the rudimentary structure.

Newton Centre has this pretentious English-style spelling and also a kind of goofy-looking hut.

I’m a New Yorker. When I lived in Boston I thought this mode of transportation was weird. Also, the weather in Boston is awful and I’m sure everyone wishes these stations provided more shelter from the elements. But to be clear, Brookline and Newton are upscale suburbs. If the residents really and truly thought it was worthwhile to build something more elaborate they could. But fundamentally, these rudimentary structures serve the transportation purpose of the Green Line which is to bring people downtown. And they’d rather spend their money on other things.

So that is what a Green Line surface station in the Boston suburbs looks like.

The idea of the Green Line Extension is to extend the other side of the Green Line out to Cambridge and Somerville, labeled here as under construction.

This is a surface root just like the C and D branch stations I just showed you. But when the GLX was coming together, the team went nuts.

Delux stations for no reason

The original plans for GLX, drawn up in 2005, called for the construction of new stations that would be rudimentary like the ones I just showed you.

But by the 2010 Environmental Impact Report, they’re saying “the design for each station is envisioned to provide a head house with automated fare lines, vending machines, an information booth, and restrooms. Entry to and exit from the platforms would be by elevators, escalators, and stairs.”

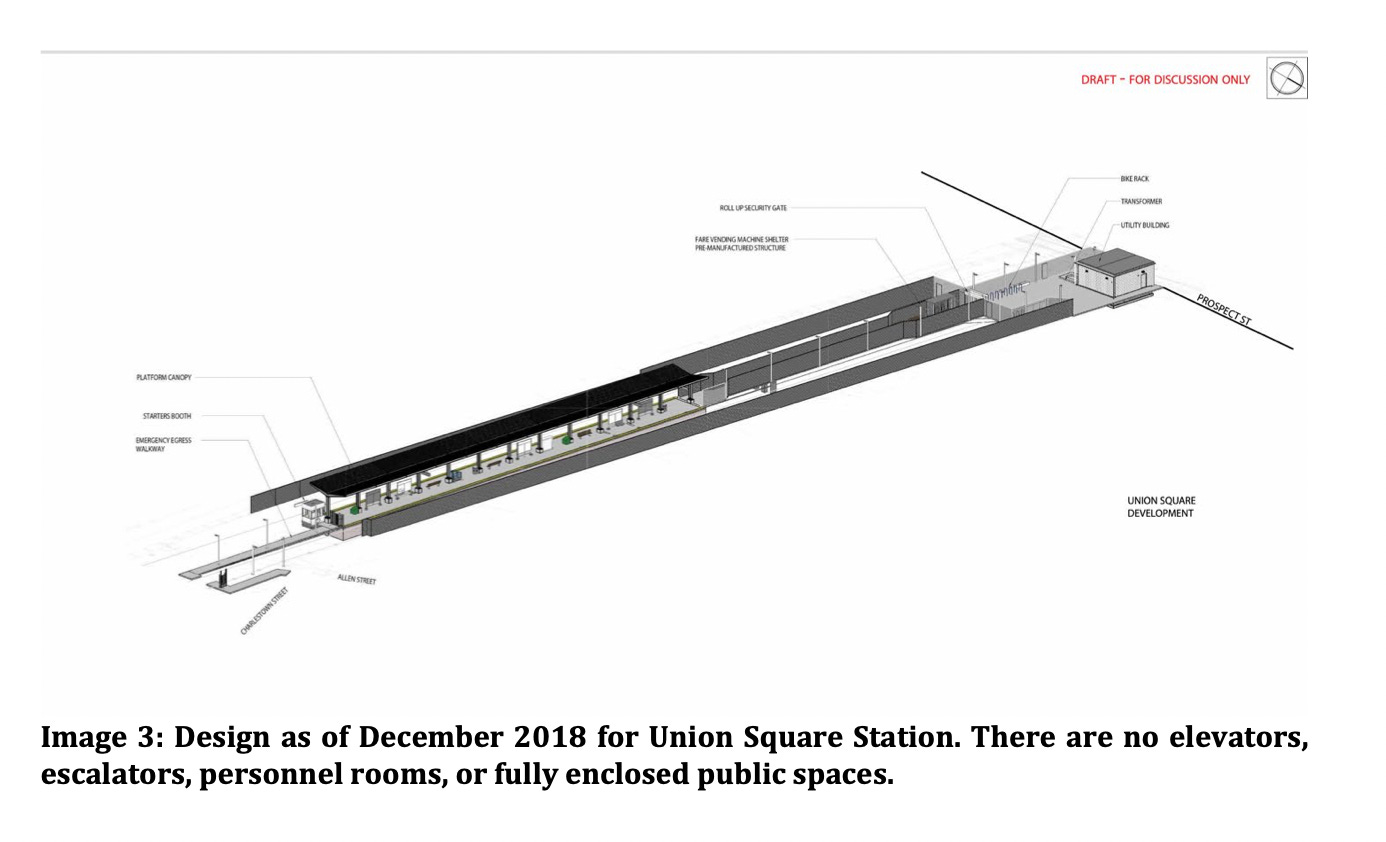

Here’s what they wanted the Union Square station to look like.

That looks cool! But by making the building so big that you need escalators to access it and elevators for ADA compliance (rather than basic ramps) you generate $2 million in costs. In total they ended up with “two levels of exterior plazas with connecting ramps and outdoor seating and plantings. In addition to these external elements, the station included a head house, bicycle storage, entryway, lobby, concourse, two elevators, two escalators, two bathrooms, employee lounge, fare vending, fare arrays, canopies, and mechanical rooms for all of the different systems.”

This just leads to a huge explosion in costs. Electrical alone costs over $5,000 per square meter so when you make the stations really big they get really expensive.

After the project almost fell apart, a new team came in with a mandate to cut station costs. They cut the total cost by 70 percent, mostly by just making the stations smaller — 91 percent smaller. The Transit Costs Projects people estimate that they saved $50 million just on electrical work.

And what’s really crazy is the finalized Union Square station design is still way nicer than the old ones in Brookline, providing a much larger space semi-sheltered from the elements.

To be clear, this station bloat is not the whole cause of the cost overruns that nearly derailed the project. But what’s striking about it is that it’s so willful and so dumb. Nobody who had ever seen a Green Line surface station could possibly have had a good faith belief that this was necessary. And it’s not like some kind of subtle scam either. It’s just consultants and contractors ginning up a bunch of unnecessary work for themselves. And yet it’s more typical than you might think.

Pointless station expense is a big problem

The Second Avenue Subway in New York cost $4.5 billion of which $2.4 billion went to the construction of three stations and the expansion of an existing one. The stations were expensive to build because they were so deep underground, and while boring a tunnel is boring a tunnel excavating a station gets very expensive when you’re deep underground.

Given that, you might want to try to minimize the size of the footprint of the stations. But instead, New York opted to build a mezzanine level above the platform level, and have the mezzanine extend across the full length of the station.

This is a typical construction type in New York City. But it’s not necessary to the functioning of a subway station. The decision to make the stations this big added hundreds of millions of dollars to an already expensive project for minimal benefit.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks destroyed the World Trade Center PATH station. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which is responsible for the PATH, chose to replace it with a signature station designed by internationally renowned architect Santiago Calatrava at a cost of $4 billion.

Stop doing dumb stuff

My fondest hope for Secretary Mayor Pete is that he can try to convince America’s transit agencies to stop throwing money at dumb ideas. This is not about pinching pennies.

By dropping the fancy stations, Boston went from “the Green Line Extension is too expensive to build” to “hey, actually we can build this.” If New York didn’t spend so much money on those Second Avenue Subway stations, they would have had enough space in the budget to build a longer line with more stations. That would mean more people directly benefitting from the appropriation, a bigger political win for the politicians involved, and ultimately just as much concrete and electrical work for the contractors. With a higher degree of cost-effectiveness, you can actually go do more stuff.

But somewhere along the way you need to stop and think about what you are doing. Does this make the trains run faster? Run more frequently? Is it necessary for safety? If not, what are we doing here? People don’t take the train to enjoy the nice stations, they take it because they’ve got places to go.

We had a town fight over a new library that I think illustrates a fundamental tension, at least in MA public projects.

- The town got a state grant to help build a new library - most of it would be other people's money.

- The town could have used a new library - the old one was small, cramped for its basic purposes, and underutilized compared to neighboring towns.

- The new plan was _beautiful_ - and expensive! It would still require a non-trivial amount of our money, partly because of how big the scope was. It was "future proofed" - we'd never need a new library again.

Since we're a town and not a city, this was the subject of a town meeting, in which there were two sides:

- People who didn't want the library because they didn't want to spend money. Their view was that the current library was totally fine, so they'd rather not pay higher taxes.

- People who wanted the new library. Their view was that the cost was small compared to the benefit.

These two groups were disjoint, and I think that's also how a project like GLX can get off the rails.

The people who want beautiful stations and bike paths are probably not fiscal hawks. They're not super concerned about the price - MA is already an expensive blue state, we all knew that coming in, and it's important to have nice public infrastructure.

The people who don't want to pay don't want to pay _anything_. They're not super concerned about the benefit, the whole project can be canceled and that's even more winning because it's even less money spent. MA is already an expensive blue state, so the right thing is to oppose everything.

The problem we have is that there's no overlap - there's no one going "yes we really should do the GLX, but also I really don't want my taxes to go up, so can we cut GLX to something minimal and not keep adding to it"?

The political constituency in MA who would say "this is too expensive" isn't necessarily motivated to show up and try to make the GLX a better value by proposing more cost-efficient changes along the way - they're motivated to try to get the thing canceled, or ignore it in the hope that it topples under its own weight.

If SFMTA has taught me anything, it’s that elevators and escalators will inevitably be broken half the time, and should only be integrated into a design when absolutely necessary. Nominal ADA compliance is asymptotic to *actual* ADA compliance.

In the Union Square example you cite (requiring elevators instead of ramps) the inevitable long-term effect is to render these stations unreliable for people who cannot use stairs (folks in wheelchairs, etc) and force them into navigating a Swiss cheese system of “which elevators aren’t working today?” where they have to travel to additional redundant stops or bus lines and then circle back to their intended destination.