Even meritocratic systems aren’t fair

Hard work and intelligence are important, but luck matters a lot.

The amount of money you’re able to earn at age 40 is in part a function of the on-the-job learning you’ve done earlier in your career. But the opportunities you got to do that learning earlier in life are in part a function of underlying competency, which continues to be relevant to your age-40 earnings.

These factors are particularly hard to untangle because, even though there are definitely hierarchies in the American education system, they tend to be a bit vague and informal — there’s no official rank-ordering of colleges or other schools.

The way the Air Force slots enlisted airmen into various career tracks, based in part on test scores, is an interesting exception to that vagueness and informality.

What makes the slotting particularly interesting is that it’s not entirely based on test scores, because the Air Force doesn’t exist to make sure everyone is treated fairly — it exists to perform a specific mission. And in order to perform that mission, it needs a specific quantity of people in specific jobs. If there’s an unusually large number of vacancies in a specific occupation at the time you happen to sign up, that increases your odds of being assigned to it, even if in a different year your score might have been just a bit too high or just a bit too low for that assignment. The average quality of the new enlistees also varies somewhat from year to year. So a score that might have been above average in 2019 when the national labor market was strong might have been below average in the weak labor market of 2010.

This allowed Julie Berry Cullen, Gordon B. Dahl, and Richard De Thorpe to conduct an interesting study where they look at what happens to people who get assigned to jobs for which they have unusually high or unusually low test scores.

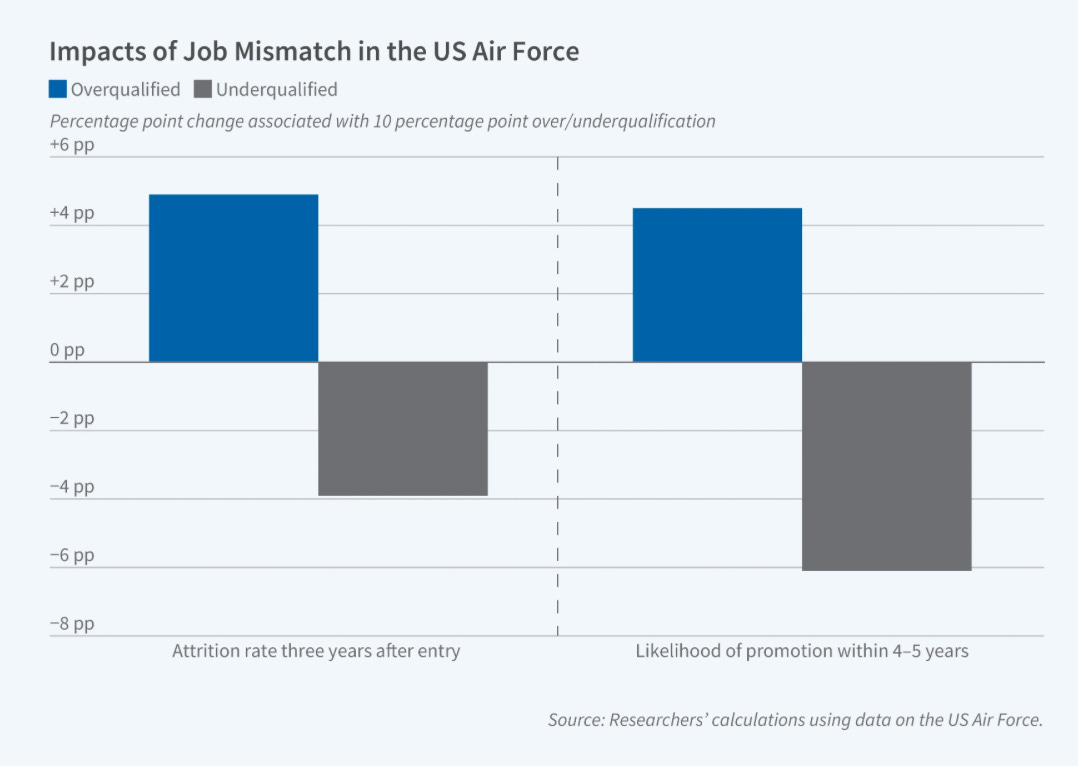

What they find is that overqualified applicants are unusually likely to quit (and underqualified applicants unusually unlikely to quit), but they’re also more likely to be promoted (again the reverse is true for the underqualified).

Beyond attrition, the people who are overqualified for their jobs display a range of problems. They manifest more behavioral issues, they get worse performance evaluations, and they do worse on general knowledge tests about the military. They seem, in other words, to be kind of pissed off and demotivated by being slotted into a career track that is beneath them.

But, they still do better on job-specific assessments and are more likely to be promoted.

I’ve found that this is an unpopular take because it’s snobby and elitist, but there’s a lot of evidence that intelligence is an asset in a wide range of scenarios, and that’s what you’re seeing here. The Air Force only has so many smart recruits to go around so they need to prioritize. But when they end up with a surplus of smart recruits, those recruits are better than average at their lower-status jobs.

The thing about this paper that is of broader interest to me, though, is that these different occupations have very different profiles in terms of earnings potential when recruits transfer to civilian life.

The researchers estimate that every 10-percentage-point increase in ability surplus leads to a 10 percent decline in predicted civilian earnings, while a 10-percentage-point ability deficit leads to a 13 percent increase in predicted civilian earnings. The long-term impacts may be smaller because differences in underlying ability typically reassert themselves. But they are still real.

The years of on-the-job training in specific technical fields don’t just vanish, you’re sort of screwed by overmatching — which the authors think helps explain why overmatchers don’t put in much effort.

Everything about this is perfectly reasonable from the standpoint of the Air Force trying to manage its personnel needs. But it illustrates an underrated point: Even totally reasonable meritocratic systems can be unfair in important ways.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.