Do we need a bigger defense budget?

The answer to a dangerous world can't just be more more more more

The U.S. spends an enormous amount of money on defense. Joe Biden is seeking a $30 billion increase in the Defense Department’s budget (a very restrained increase when you take inflation into account), but Congress seems likely to appropriate considerably more funds, for a total DoD budget north of $813 billion.

But Kori Schake writes in Foreign Affairs that we ought to be spending dramatically more, arguing that “the changes needed to bring the Defense Department’s budget back in line with its strategy involve a hefty price tag: around an additional $384 billion per year, a figure about 50 percent greater than the current Pentagon budget.”

The political economy of the late-Obama years plausibly led to underspending on defense as part of the goofy dynamics of the budget sequester and the austerity politics that dominated after the 2010 midterms. And on macroeconomic terms, I was not critical of the Trump-era surge in military spending — the economy handled the ballooning budget deficits just fine, and Congress was consistently increasing domestic spending during those years as well. As a question of politics and economics, the buildup was fine. Today’s inflationary situation is different, though, and in most cases resources consumed by the defense establishment probably do come at the expense of the civilian economy. Noah Smith argues that life is more complicated than a simple “guns or butter” tradeoff, which is true. But I still think we have moved from an era in which the economy was operating well below potential and the tradeoff was mostly fake to one in which we are facing relevant supply-side constraints.

I’m open to Schake’s argument, but the article doesn’t address the skunk in the room: in 2020, the United States spent more than twice the combined defense budget of Russia and China. If we are nonetheless leaving critical holes in our capabilities, that strongly suggests either a profound failure to set appropriate priorities or else a badly broken contracting model.

A detour into purchasing power parity

To say that spending twice as much as Russia and China combined is inadequate seems absurd on its face. And it’s rendered even more so by the fact that whatever their shortcomings, America’s allies are clearly more formidable than Belarus and Cambodia.

This leads some to argue that, as Michael Kofman and Richard Connolly wrote in 2019, “Russian military expenditure is much higher than commonly understood (as is China’s).” Their case is that these comparisons are more relevant when made in terms of Purchasing Power Parities rather than market exchange rates, which does in fact shrink American defense spending while raising that of basically every foreign power (including our main allies).

I think the dismal military performance of Russia in Ukraine should cast some doubt on the idea that the Russian military was secretly much more formidable than estimates indicated. I also know more about PPPs than I do about military procurement, so I feel confident saying that Kofman and Connolly are mostly wrong.

They do make the good point that using market exchange rates generates a sense of excess volatility in military spending. For example, in 2014 the global price of oil tumbled. That led the value of the ruble on world markets to tumble, so charts show that Russia’s defense spending tanked during this period. And if Russia were a country that imported tons of western military equipment, the ruble’s plunge really would have put a squeeze on their procurement. But they’re not. There was no plummet of Russian military spending followed by a sharp rebound — in ruble terms they basically held steady.

But economists are aware that foreign exchange methods display excess volatility and can use the Atlas Method to smooth out the fluctuations.

PPP is something else; it’s a cost of living index. Say a big global bureaucracy (a company, an NGO, a government, whatever) needs to send some employees to Oslo and some others to Nairobi. The actual work they’ll be doing is similar and requires similar skills, so you want to pay them all roughly the same amount of money. PPP reminds us that even though many globally traded goods cost roughly the same amount in Oslo and Nairobi, much of what people buy in their daily lives are non-traded local services. And it is dramatically more expensive to hire a Norwegian person to cut hair or serve a restaurant meal than to hire a Kenyan person to do the same. PPP, by looking at the local price of a bunch of stuff, tries to adjust for this and says you need to pay your Oslo-based staff more than your Nairobi-based staff to account for the fact that non-traded goods are so much more expensive in Norway.

In that sense, PPP is important. But the concept doesn’t always make sense expanded to other domains.

For instance, some PPP-heads say that China has already surpassed the United States to be the world’s number one economy. But have they?

The point of the Oslo/Nairobi PPP adjustment isn’t to say that Kenya is “really” richer than it seems. The point is that precisely because Kenya is poor, you should revise downward the salary of your Nairobi-based staff relative to what you pay employees in rich, expensive Oslo. In China, despite decades of growth, it’s cheap to buy unskilled labor compared to the United States. That’s not the same as saying the Chinese economy is larger than ours; particularly for something like that, the ability to buy globally traded goods is important.

In military terms, this comes down to what are you spending money on.

Doing a principled comparison is really hard

Let’s return to our hypothetical global bureaucracy.

Imagine this organization needs to rent a nice office with space for 10 foreign employees, hire one local person as a receptionist and another to clean the office, and purchase things like computers, a refrigerator, and some coffee machines. The budget for this wouldn’t make sense in terms of a generic PPP basket. You want to ask what that stuff actually costs. A lot of those things are globally tradable, and I wouldn’t be shocked if it turned out that computers cost more in Nairobi than in Oslo. But the office rent is presumably less in Nairobi, and the local cleaner is definitely less. The point is, you’d have to ask what these specific things cost.

Peter Robertson of the University of Western Australia created a military-specific PPP comparison and reached the conclusion that the “real” military spending — not just of Russia and China, but also of Ukraine and tons of other middle-income countries — is badly understated.

The individual country results for the largest countries are summarised in Table 1. It can be seen that market exchange rates generally underestimate real military spending and that the difference is dramatic. China’s budget in military-PPP terms is 1.62 times larger than the market exchange rate figure. Moreover, India, Russia, and Turkey have budgets that are more than three times the market exchange rate value and some middle-income countries, such as Indonesia and Ukraine, have real military budgets that are 5–6 times the market exchange rate value.

This accounting at least reconciles the “Russia’s military is underrated” theory with the observed fact that we actually overrated it, because he says the Ukrainians were even more underrated.

Basically the theory here is that poor countries can hire soldiers for cheap. As this Economist piece put it, “entry-level pay for soldiers is 16 times higher in America than in China.”

I wonder about this, though. During the Vietnam War, the United States had a cheap military based on conscription and also a general understanding that high-socioeconomic status people could generally avoid being conscripted. We moved away from that model in favor of one that has higher per soldier costs but that also recruits better soldiers. The service academies that churn out our officers draw from the top third of the SAT/ACT distribution. Enlisted troops need to meet minimum scores on the AFQT (this is basically an IQ test), and in the vast majority of cases, they must graduate from high school in order to serve. Military service is also fairly prestigious in the United States, with veterans overrepresented in Congress relative to their share in the population by about four-fold.

In other words, we certainly could cut personnel costs. Russia relies on conscripts brought in via an easily evaded draft augmented by “contract soldiers” mostly drawn from the poorest parts of the country, which are the only places where the pay is attractive. It’s basically what America had in Vietnam, minus the NCOs. America has deliberately adopted a strategy that is more expensive in order to get a better military. American soldiers are led at the squad (and to an extent, the platoon) level by professional senior NCOs with years of experience. You could try to argue that this is all a mistake and we should revert to a cheaper personnel model, but nobody seems to actually think that. So you can’t just do a crude pay comparison — you get what you pay for.

The problem with equipment comparisons is that the market for military hardware is highly segmented. Australia and Canada basically buy from the same group of sellers, so you can just compare their money. To the extent that Australia buys stuff that Canada doesn’t (and vice versa), it’s all stuff that Canada could buy, so just comparing the prices is sensible. But Russia and China don’t buy NATO hardware and NATO countries don’t buy Russian or Chinese hardware. So you have to ask what the equipment actually does and whether it’s any good.

What are we doing here?

Note that Schake said we need to spend hundreds of billions of additional dollars on the military in order to “bring the Defense Department’s budget back in line with its strategy.”

That’s consistent with the idea that the strategy is bad.

For example, I don’t think the United States should be in the business of defending Europe from a Russian attack. We should be as helpful as possible about this. But the European Union has drastically more money and manpower than the Russian Federation, and we should be working with them to ensure that French, German, Spanish, Italian, and British soldiers are positioned to do a forward defense of Poland and the Baltic states while encouraging Sweden and Finland to join NATO.

More broadly, the upshot of all these efforts at PPP comparisons is that just as in global trade, the United States is well suited to do things that are technology-intensive and poorly suited to do things that are labor-intensive. Having American infantry squads walking around Iraq trying to do preventative security policing was very poorly suited to America’s comparative advantage in the world. It’s true that a “strategy” that calls for this is extremely expensive, but that’s in part because it’s a bad strategy. By contrast, gathering lots of intelligence (via satellites, drones, whatever electronic snooping capabilities), building lots of weapons, and then giving intel and weapons to Ukraine to use against Russia is a very good, very cost-effective strategy that plays to our strengths.

And there’s actually a convenient correspondence between what strikes me as the most legitimate strategic focus for the United States (helping friendly countries defend themselves from attack) and our comparative advantages (R&D, high-tech manufacturing, intelligence). It’s the inherently labor-intensive task of physically controlling a foreign population that is so costly. Our military has spent a lot of time during my life attempting to pull off that kind of mission, often for bad reasons, and it didn’t work very well.

We need a strategy that focuses on better goals, like maintaining a qualitative technological advantage in scalable military products that can be purchased and/or given away to friendly countries. We should also be strongly prioritizing the formation of an alliance with India, a country that is poor and has a huge population — you could imagine a highly complementary relationship between the U.S. and India to check China with a mix of technology and manpower. But achieving that edge in scalable hardware requires asking some tough questions about procurement.

It’s bad to waste tons of money

I’m not going to solve defense procurement in a blog post, but I do want to note that there is some kind of profound problem here comparable to the cost overruns that I’ve come to understand in the mass transit space.

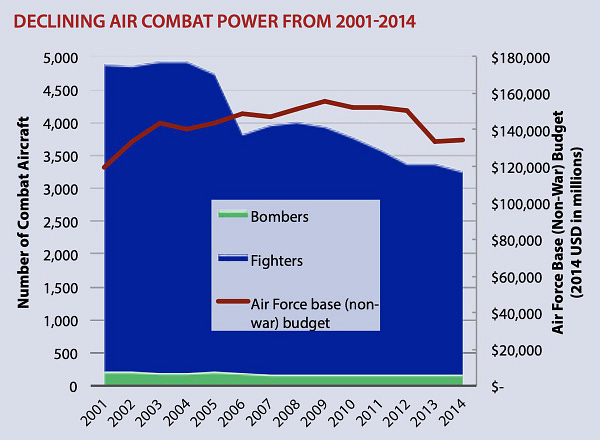

In recent years, the military started complaining that its amount of available firepower for a great power conflict has declined due to the expenditures on the Global War on Terror. But as Paul Scharre shows, even if you look exclusively at inflation-adjusted non-war money, the Air Force is getting less stuff for more money, and something similar is at work in the Navy.

The F-35 project is a legendary disaster, but in some ways, the Ford-class aircraft carriers are an even clearer example. They cost $13 billion a pop over and above massive R&D costs that can’t be spread out with international sales because nobody wants a gigantic $13 billion aircraft carrier. And they aren’t just expensive; it seems like in the event of a war with China, they wouldn’t actually be used because China’s short-range missiles are too good (this is called A2/AD for “anti-access area-denial” in military jargon). For a really strong version of this case, you can read former John McCain staffer Christian Brose’s book “The Kill Chain” in which he argues that almost all the big American military platforms are nearly useless.

Robert Farley correctly argues that this is overstated — over the past several decades, we have gotten a lot of mileage out of using aircraft carriers to fly planes into uncontested airspace and will continue to find things for them to do in the future.

But to the extent Schake is right that we have important unmet spending needs, it’s important to acknowledge that this is in part because we appear to be spending very large sums of money on projects of questionable value. The market for military equipment isn’t a traditional kind of market, but I do think injecting some market thinking into topics like aircraft carriers is useful — if the U.S. government is the only buyer for a given piece of hardware, that suggests the program is not very compelling on the merits and is being driven by domestic political considerations. At the other end of the spectrum, the shoulder-launched anti-tank missiles that we’re seeing used in Ukraine are clearly very cost-effective ways of blowing up enemy vehicles, and every country is going to want to buy some. That’s the kind of thing you want to be developing — products for which there will be strong demand, whether or not we decide for strategic reasons to ultimately approve the sales.

For most of my career, I was not very worried about the idea of the military wasting money on low-value hardware — interest rates and inflation were almost always low, unemployment was almost always high, and it just didn’t seem worth fussing about. Today’s macroeconomic circumstances are different, though, and expensive military projects really will crowd out potentially useful private spending or domestic social programs, so we need to be more cautious.

Can we improve contracting?

I don’t know a lot about space policy, and to some extent I find space enthusiasts to be baffling people.

But I did really enjoy two Eli Dourado posts about NASA contracting — one about the very wasteful Space Launch System and one about the successful Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) contract — that I think have important implications for defense policy.

Often, and in the case of the Space Launch System, NASA puts out a very detailed Request for Proposals saying exactly what it wants, and really only a tiny number of well-connected insider companies are positioned to adequately answer all the specifications of the RFP. And then there is the difficult problem of overseeing the contractor as it tries to fulfill the terms of the agreement. The structure of the whole thing is a “cost-plus” arrangement where NASA agrees to pay the contractor whatever it cost them plus an increment for profit. Basically, the contractor gets paid more for making the thing more expensive and leaves NASA on the hook for delays or overruns.

For COTS, though, NASA used its authority to engage in “other transactions” that are technically not procurements and structured the whole thing differently:

In addition to this legal distinction, COTS differs from traditional procurements in other ways. First, each of the companies selected was expected to pay part of its own development costs. This ensured that the companies were building something useful they could go on to commercialize — they would not have agreed to share costs to build something they knew was inefficient.

Second, the use of fixed-price, milestone-based payments limited the amount of oversight necessary to ensure success. It allowed NASA to turn over development entirely to the companies, knowing that it was only on the hook for payments when the programs successfully met pre-defined milestone criteria.

Third, NASA didn’t dictate the vehicle’s requirements. They evaluated the proposals based on the goal of providing reliable cargo service to the ISS, but they didn’t specify the technical means that participants could use to achieve that goal.

Basically, NASA said, “if you can build a thing that does X, we will pay for it — you figure out the rest.” SpaceX wound up building the Falcon 9, which earned them money from NASA but has also gone on to become a successful commercial product.

Now you can’t apply exactly this model to military procurement because of course we’re not going to let a company develop the world’s deadliest weapon and then sell it to random hobbyists or rogue states for profit. But I do think the basic model has a lot of appeal and application to the defense realm. Notably, if we want to be the arsenal of democracy (and we should), then it really does make sense to incentivize companies to develop products that have broad appeal to a wide range of friendly states rather than being hyper-prescriptive about exact designs. And even more importantly, to the extent that we think computers and unmanned systems will be an increasingly significant part of war (and we should absolutely think that), then we want to open the ecosystem to input from companies with an IT rather than aerospace legacy, as well as to startups and new entrants.

We need a winnable race

Convincing Congress that we should totally overhaul military procurement is a difficult sell, as is convincing the Navy that they need to find a way to live without gigantic bespoke aircraft carriers

It’s easier to just give the military more money while also not giving them nearly as much money as Schake thinks they need. Because giving them that much money would actually be very difficult and push us squarely into the realm of tradeoffs. Now you can say “well, too bad, the civilian economy just needs to suck it up and deal with the needs of the military-industrial complex.” But I don’t think that is ultimately any easier politically than trying to reform the procurement system.

But it’s also not strategically tenable. If we want to go with the PPP-adjusted numbers, then the key fact is that the American economy is already smaller than China’s. We’re not, in the long run, going to be able to beat them in a PPP-adjusted spending race. To maintain a lead, we need to do three things:

Focus on growing the American economy, which is the ultimate wellspring of national power.

Focus on the fact that most countries would rather ally with the United States.

Focus on our comparative advantage in advanced technology.

This means spending more intelligently on high-tech stuff with broad demand and spending an amount that does not prevent us from making important investments at home. Lead remediation, developing new sources of energy, and otherwise strengthening the domestic economy — ideally by growing the population — are as important if not more so to national security than short-term military spending.

I work in the humanitarian sector and at a previous job did a lot of software contracting with USAID projects. It was basically impossible to structure any of the contracts in a way that produced good software at a fair price – in fact, we often produced software that wasn't used, was overpriced, AND we somehow made a loss on it. It's no individual's fault in the contracting chain but the end result is basically insane.

We tried to get away from the cost-plus ('time and materials') model to just paying us a fixed price for a product, but that just led to constant back-and-forths on whether things really matched the requirements and what was a new feature request etc. etc. Ultimately cost-plus was safer for both sides, but it rarely resulted in good software. I work in the same field, but with a much better, non-government structure now. I think military contracting largely functions like USAID, and it's so difficult to fix how it works.

I don’t particularly agree with this take because if you look at the Department of Defense’s budget justification books (which I do for a living now) you’ll see a fair amount of the defense budget (& future outlays) are dedicated to military salary, retirement, healthcare and not specifically defense related military construction. A fair portion of our defense budget has very little to do with lethality or competing with the PLA (assuming that we ignore European security, which I disagree with as well).

The point that procurement is wholly broken I 100% agree with. The Ford-class carrier is an okay example but a bigger example is the botched procurement of the Littoral Combat Ships (which are being retire well before their service life, some basically new) and the Zumwalt-class DDGs (only made 3 with guns that we couldn’t afford the ammo for). Another commenter mentioned the Navy should notionally be the lead service in directing the competition against the now larger People’s Liberation Army (Navy) but the US Navy is incapable of building or developing new ships for that competition because of decades of not investing in public & commercial shipyard infrastructure. Trying to reorient the Navy & to a lesser extent the Air Force will require more money and more than the nominal 4% defense increase from last year (2% if you take out the Ukraine supplemental funding).