Democrats' strange victory in the 2022 midterms

The normal backlash materialized — but not in the key races

Interest in election analysis tends to peak the day after the election, which is unfortunate because even under modern conditions, we don’t have accurate vote counts that quickly. Hot takes based on exit polls with very low reliability and impressions tend to congeal quickly.

For my money, the best source of information about who voted for whom is the “What Happened” reports that Catalist puts out months after voting is done. Because Catalist isn’t a media company that’s trying to maximize clicks, they take their time and match survey data with data from their extensive voter file. Their “What Happened 2022” report is now available and I’d recommend that anyone who’s interested in U.S. elections read it.

What really stands out to me this year is something that I think is a little unfashionable but hard to deny: Democrats did a really, really good job, on a technical level, at the blocking and tackling aspects of running effective political campaigns. They raised a lot of money, both from small donors and through large super PACs, and they seem to have been quite effective at translating that money into ads and other campaign messages that voters in key states and districts found persuasive. There are limits to how much this can accomplish, but in close races, it matters a lot.

A different kind of non-wave

After successive down-ballot landslides in 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018, the notion of a “wave” election became so ingrained in the discourse that I think we sort of lost sight of what a non-wave election might look like. But to understand why observers were initially so impressed by those waves, consider a map of the 1998 Senate elections, which were a wash even though six seats changed hands.

To an extent this is just a different era, one in which Democrats held seats in Arkansas, Louisiana, and South Carolina. But it’s important to note that even back in 1998, South Carolina was more GOP-friendly than Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, Arizona, or Georgia. Democrats gained a seat in Indiana while losing one in Illinois. Bill Clinton won Ohio in 1996 and lost North Carolina, then two years later the Ohio senate seat flipped blue and the North Carolina seat flipped red.

This was, in other words, a non-wave election. The national political climate mattered (the typical midterm backlash was neutralized by a sense that the GOP was overreaching with impeachment), but you can’t really explain the specific results in terms of national trends. There were strong incumbent effects, local news coverage was very important, voters were less cognizant of big-picture partisanship, interest groups did more cross-endorsements — politics was, generally speaking, very complicated. Sometimes a big partisan “wave” would crash across the country (as in 1994) and everything would break one way. But elections would frequently turn on the specific dynamics of something like a politician’s personality.

Or for a truly classic non-wave, look all the way back to 1984 when Ronald Reagan won in a crushing landslide and Democrats gained two net seats in the Senate.

That was a long time ago, but it’s important to understanding the development of the concept of the “wave” because it’s not like 1984 was a close election. It was a huge landslide. But it wasn’t a wave. Down-ballot voters were picking based on candidates or matchups or local concerns. In part that’s because it was a different time. But in 1980, Reagan did have long coattails that generated a wave, and in 1982 there was a midterm backlash wave. So it’s not like waves never happened; it’s just that they only happened sometimes.

The non-wave of 2022 differed in several key waves from those older non-waves. In 2014, Democrats did 4 points worse nationally compared to 2012. Then in 2018, Democrats did three points better nationally than they’d done in 2016. In 2022, Democrats did three points worse nationally than in 2020. Same old, same old. But what made 2022 different, per the Catalist data, is that Democrats did way better than average in precisely the closely contested races where it mattered most.

That’s highly unusual. In both 2018 and 2014, the swings were uniform. The tossup districts are very different from the base districts, but there are a certain number of moderate, cross-pressured, or otherwise persuadable voters in any given district. And in recent elections, the persuadable voters have tended to lean one way or the other basically everywhere. But 2022 wasn’t like that. In the safe districts, a healthy number of Biden voters flipped to the GOP. But in the swing districts, they didn’t. Because most seats are safe, the overall national result (-3) is much closer to the safe seat result (-4) than it is to the tossup seat result (0). But because the tossup seats are the ones that actually matter, the outcome wound up being really strong for Democrats.

Changing women’s minds

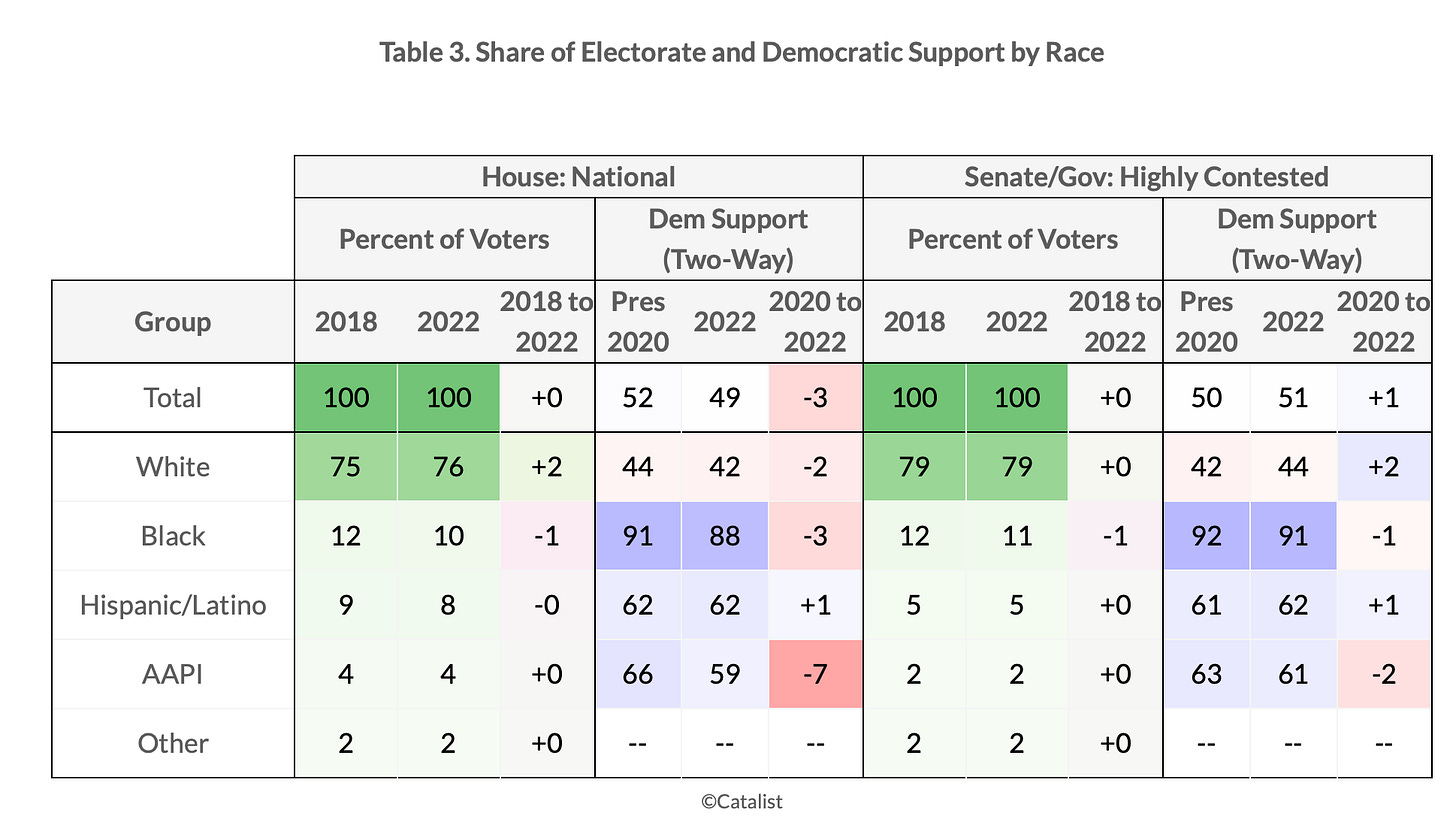

So who was persuaded by Democrats’ campaign messages in the swing states? Looking at the national House vote shares by race, Democrats were basically flat with Hispanic voters but lost ground with white, Black, and Asian voters relative to 2020. In the highly contested races, they did about the same with Hispanic voters, slightly worse with Black voters, slightly better with white voters, and quite a bit worse with Asian voters.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.