Congressional Republicans’ coming war on poor people

What we know about GOP reconciliation plans

Donald Trump is nothing if not a master of attention, and the eyes of the world have been on his executive orders. With most of these, my sense is that there’s less to them than meets the eye, primarily because that’s just the nature of executive orders: It’s not usually the case that you can dramatically alter public policy with presidential memos. There are a few exceptions that I want to dig into later, but the biggest stakes in elections really are the legislative agenda, and the biggest impact of a Republican being elected president is that he will sign bills that Kamala Harris would have vetoed.

This means, first and foremost, some kind of tax cut bill, partially or entirely offset with some kind of major spending cuts. Many things about this are true simultaneously:

It’s hard for Republicans to pull off, because their House majority is very narrow.

It’s unprecedented in recent history for the House rather than the Senate to be the “hard” part of major partisan fiscal legislation, so the dynamics are difficult to predict.

It’s inevitable that something big will happen here because it is genuinely inconceivable that Republicans would just let the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act expire.

Democrats are on much firmer ground politically contesting GOP priorities on core fiscal issues than almost anything else, except January 6 pardons.

I don’t want to say that everything else that’s going on is a distraction, but it is wise for everyone to be mindful what they post about and what the politics are.

There is a huge amount of uncertainty about what will actually happen here, but Republicans made it pretty clear through their early memos that, in broad strokes, what they want to do is take medical care and nutrition assistance away from poor families in order to facilitate regressive tax cuts. How and why this all comes together is very much TBD. But it’s useful to start from the top with a reminder of the budget reconciliation process and the relevant constraints.

Two congressional maths

The premise of all of this is that Republicans will cut taxes in a budget reconciliation bill, rather than going for a bipartisan bill that could secure 60 votes in the United States Senate. One could question the tactical and strategic wisdom of this choice, but absolutely nobody in the GOP caucus is questioning it, so I’ll leave it unquestioned for these purposes.

If you look at the big Democratic reconciliation bills of 2021-2022, the core question was, “What will Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema vote for?” And if you look at the big GOP reconciliation bills of 2017-2018, the core question was, “What will Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski, and John McCain vote for?” If you go back to 2009-2010, while the Affordable Care Act ended up being pushed over the line by a reconciliation rider, the main legislation was actually a bill that passed the Senate with 60 votes, so the main question was, “What will Ben Nelson and Joe Lieberman vote for?” Jim Jeffords from Vermont, similarly, was the pivotal vote on the 2001 Bush tax cuts. Which is just to say that these have all been Senate-driven processes. In my adult life, House dynamics have been the most relevant factor in trying to pass bipartisan bills. At one point, progressive House members threatened to sink the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that had passed the Senate, and Conservative House members did sink the Gang of Eight immigration bill that passed the Senate in Obama’s second term.

But I can’t think of a situation in which House moderates were the relevant sticking point.

This time, though, the GOP can afford to lose Collins and Murkowski and a third senator and still pass bills with 50 votes, plus JD Vance. It’s not really clear to me who the pivotal senator is in this dynamic. In the House, by contrast, there are currently 218 Republicans and 215 Democrats, plus two vacancies that will probably (though not certainly) be filled by Republicans via special election. Three of those Republicans (Bacon, Lawler, and Fitzpatrick) represent districts that Kamala Harris won, and there are a lot of other close ones. The question of what frontline House Republicans will swallow is not really something that’s ever been tested, but it’s going to be critical here.

The constraints and the forcing action

Even though the House is where Republicans will struggle to get the votes, the Senate rules governing budget reconciliation are still a binding constraint.

The key thing here is that the Congressional Budget Office scores legislation for its budgetary impact over a ten-year window. But to pass muster under reconciliation rules, a bill cannot raise the long-term budget deficit. When Republicans were putting the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act together, the way they did this was to first raise a certain amount of revenue by closing tax loopholes — capping the SALT deduction, for example. They then wrote a bunch of tax cuts, the cost of which on a year-to-year basis was a lot more than the revenue they raised by cutting loopholes. But then, they scheduled a bunch of those tax cuts to expire — specifically, to expire this year — so that the bill scored as reducing rather than raising the long-term deficit.

Now the cuts are set to expire, and what conservatives would like to do is make them permanent by offsetting them with spending cuts.

This is important substantively, because defaults matter a lot in American politics. Since Republicans won in 2024, it turned out not to be so bad for the right that so much of TCJA was written as temporary. But a very small shift in the macro-political environment would have given us President Harris and Speaker Jeffries. In that world, even though Democrats didn’t hold the Senate, they could (and would) have used TCJA expiration as leverage to force Senate Republicans into making concessions. Had TCJA been made permanent in 2017, that leverage wouldn’t exist. So among policy-minded conservatives, achieving permanence is important to the long-term trajectory of policy. This is probably not important to Donald Trump, personally, but it’s a big deal.

Of course, Republicans could have made TCJA permanent back in Trump’s first term by finding offsetting spending cuts. They didn’t because they felt they didn’t have the votes for this. Are things different now?

One thing that is different is that back in 2017-2018, we were still at a time of low inflation and low interest rates with the prime age employment-population ratio below historic norms. Today, none of that is true. Which is to say that even absent budget reconciliation rules, it’s probably not advisable to take policy steps that increase the long-term budget deficit. Doing so will place more inflationary pressure on the economy, which will probably translate to higher interest rates. Republicans are also constrained by the fact that they’ve promised not to cut the two largest domestic programs (Social Security and Medicare) and they want to increase spending on the military and border enforcement. So there’s pressure to cut spending and also tight constraints on what spending can be considered.

The upshot is they’re currently looking at big cuts to spending on the poor.

What’s on the menu

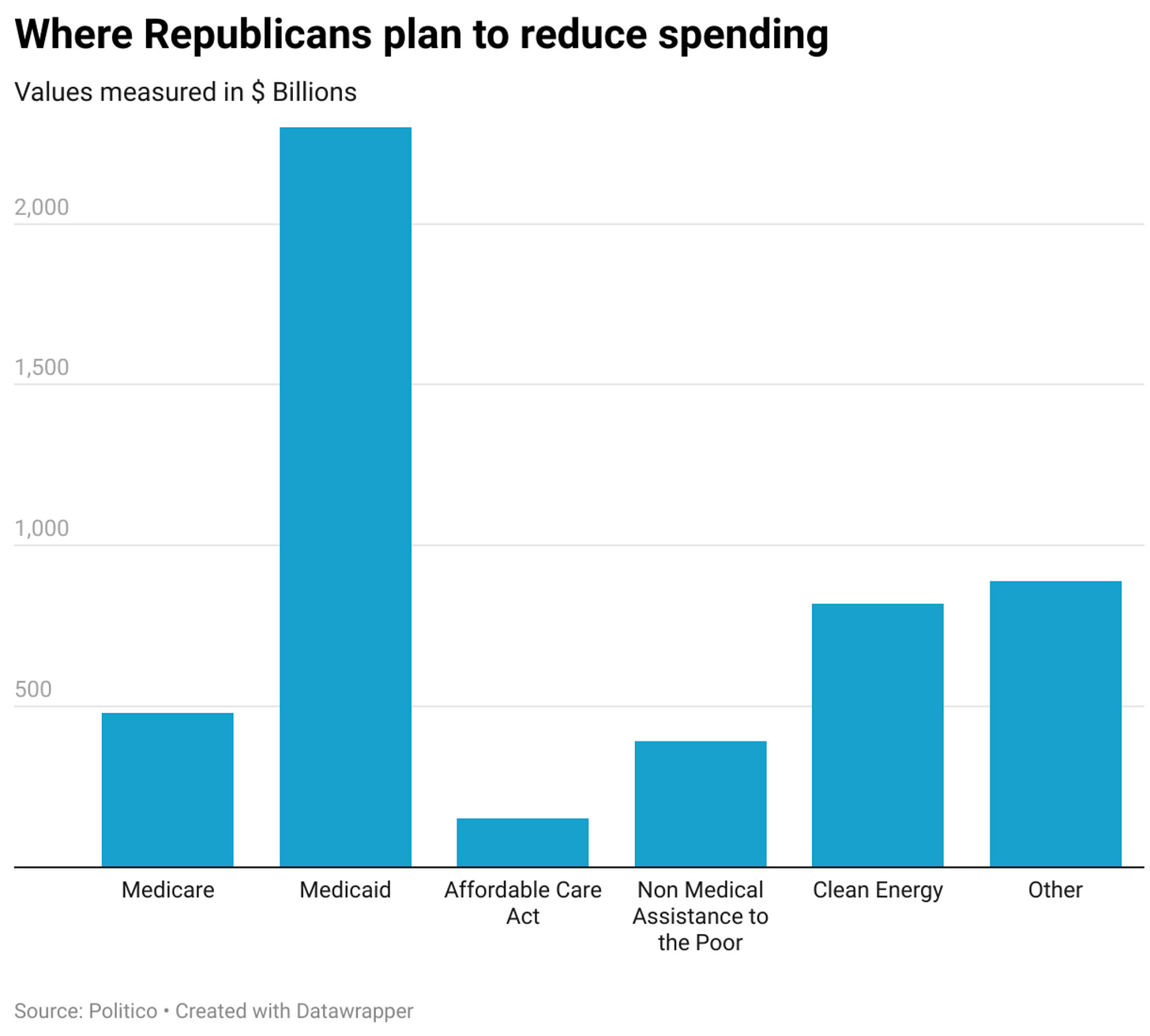

Republican leaders on the House Ways and Means Committee kicked the process off by outlining a “menu” of potential budget cuts that add up to north of $5 trillion in offsets, mostly coming from health care programs.

That doesn’t mean the whole menu will be for dinner. According to Punchbowl, leadership is hoping to get somewhere between $2-3 billion worth of cuts in the bill.

In line with that smaller number, here are the specifics they’re reporting:

“Up to $2 trillion of cuts” from work requirements and other Medicaid cuts

“Up to $500 billion in cuts” from education, mostly looking at student loans

$100-250 billion in cuts to SNAP

A long tail of smaller cuts

The biggest differences between the Punchbowl reporting and the menu come from Medicare and clean energy programs. The Medicare cuts from the menu were basically a good idea, a reform known as “site-neutral payments.” The United States has a lot of hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) or ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) that perform procedures that don’t require overnight stays in a hospital bed. Many of the procedures that can be done at a HOPD or an ASC can also be done in a regular doctor’s office. There may be reasons to think the HOPD or ASC model is superior to a basic doctor’s visit in some cases, but right now, Medicare arbitrarily reimburses HOPDs and ASCs at a higher rate. That costs the government money and also generates perverse incentives.

I’m hoping that the reason this didn’t make the list is just a question of committee jurisdiction and that it’ll be included by Ways and Means in the end. Alternatively, Republicans decided they didn’t want to piss off the hospital lobby, so they left it out.

The aspiration to cut back on Inflation Reduction Act clean energy subsidies seems to have been scaled back for the more straightforward reason that a critical mass of Republicans don’t want to cut some of these programs because they’re good for their districts.

The student loan cuts I frankly would support in a different context. After their broad student loan forgiveness initiative got thrown out by the courts, Biden’s education department re-wrote the regulations governing the student loan program to make it more generous to borrowers in a range of ways. Most of what they did here is reasonable, but I wouldn’t say that any of it struck me as a particularly high value use of funds. It was done because it was a thing the administration could do without a congressional vote, whereas other higher-value things would require a new law. But that makes rescinding it a juicy pay-for for Congress. And if they used it to finance a balanced deficit reduction bill or for some other worthy purpose, that could be fine. Using it to offset regressive tax cuts, though, I don’t love. But the main problem here is the Medicaid and SNAP cuts.

The war on poverty poor people

A generation ago, David Stockman talked about how he became Ronald Reagan’s first OMB Director and was excited to go to work on shrinking what he saw as the bloated American state. But in the end, he felt they went after “weak claimants” rather than “weak claims.” And that’s what this effort to reduce spending on the backs of the poorest people in the country amounts to. We have farm subsidies and Social Security benefits that go to people with above-median incomes. We have a Medicare Advantage program that is rife with overpayments to rent-seeking insurance companies. And then we have… health care for poor families.

The Republican view is that it’s politically better and easier to finance tax cuts for the rich at the expense of the most vulnerable people in the country, and they may be right that it’s easy, but I find it pretty hideous.

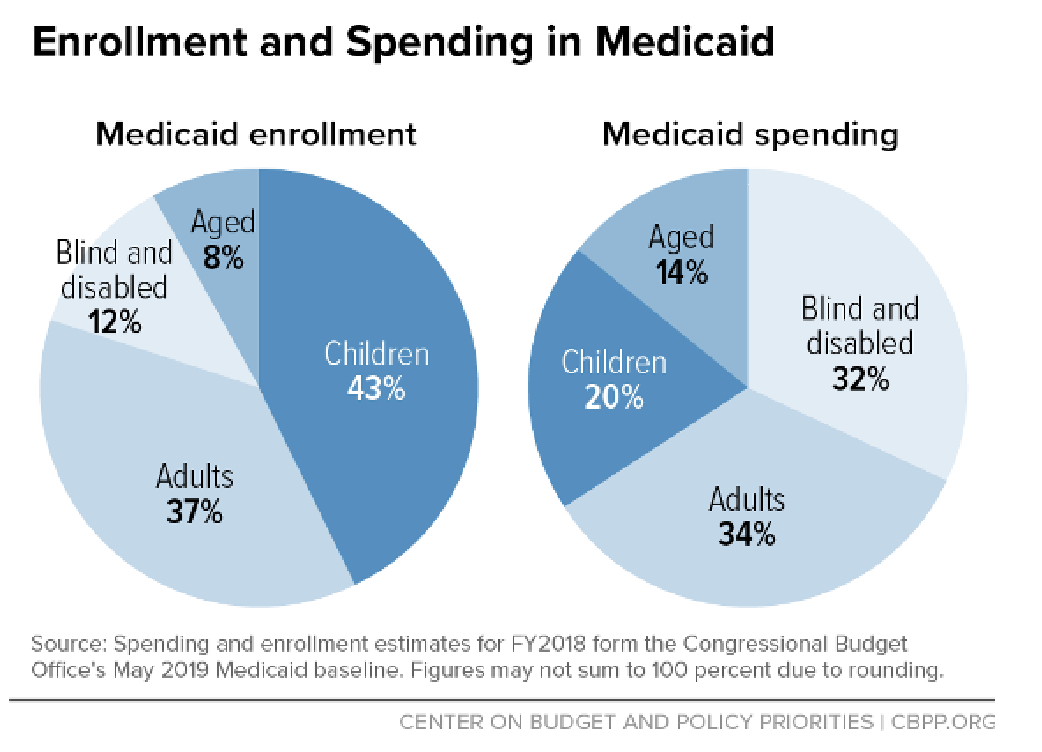

The biggest idea here is barely even an idea, it’s just to impose “per capita caps” on federal Medicaid spending. Right now, Medicare pays providers a lower reimbursement rate than private health insurance, and Medicaid pays an even lower reimbursement rate. So although it’s an expensive program, it’s also a quite thrifty one. Poor people are not getting lavish benefits, and a large share of providers refuse to see Medicaid patients at all because the reimbursement rates are so stingy. Per capita caps on Medicaid spending don’t do anything to make the program more efficient or to target waste. They just save money by saying that federal willingness to pay for a covered person’s health care won’t grow even if the cost of providing care for that person does grow.

In terms of the population that will be hurt by this, we’re looking primarily at poor kids. Kids are relatively cheap, though, so unless you want to hit them with really savage cuts, you’re also going to need to stick it to high-need disabled people.

Trump has a habit of evaluating economic policy based on stock market reaction, and it’s true that unlike with broad tariffs, there’s no reason to think the S&P 500 would object to taking medical care away from poor kids and the disabled to pay for business tax cuts. Your mileage may vary on the ethics of that.

Finally, the GOP plans to cut SNAP benefits. The backstory here is that the 2018 farm bill, signed by Donald Trump, directed the US Department of Agriculture to periodically update the USDA’s official Thrifty Food Plan, which is a basket of groceries that the US government thinks reflects what a representative family of thrifty people need to eat. This was quietly done in 2021 by the Biden administration and made the program more generous for the vast majority of recipients. Dylan Matthews hailed it as one of the best things the Biden administration did. But even though that 2018 farm bill passed a Republican Senate and was signed by Trump, Republicans have always hated the revisions, saying the TFP update was never intended to actually help poor families or cost money. Now it’s available for them to crawl back to offset tax cuts.

This was a pretty high-level overview, in part because I suspect there will be plenty of opportunities to cover all of this in more detail going forward.

But opposing this kind of thing is, I think, at the core of a big-tent Democratic Party. I believe in a growth-friendly economic policy that rejects the fantasies of post-neoliberalism, and also in an economic policy that commits not to leaving the vulnerable behind, or putting them first in line for sacrifice if fiscal austerity is needed. It’s long been the case that GOP-aligned states that benefit more from these safety net programs tend to vote Republican. But a big change over the past three presidential cycles is that a much larger share of actual poor people who use SNAP and Medicaid have started voting for Trump. Defending their interests — and communicating about it — is integral to winning those votes back and to rebuilding a more functional politics.

For all the shit he catches from “the left,” nobody describes the concrete materialist stakes like MattY.

Also, for all the squabbling post election, it’s crystallizing to see who the enemy is - The GOP exists really, to do this, to cut income and capital gains taxes for high earners and reduce wealth distribution. If you think that’s bad, the guns point that way.

It's remains incandescently stupid that the only bipartisan sacred cow is transfers to wealthy retirees. No side in these budget fights is defensible as long as Social Security is an unfixable political quagmire.