Confessions of a former “studies say” guy

Wrestling with questions about how we know what we know

Reading the many rounds of back and forth over whether it’s actually true that Mississippi generated sustained improvement in its early literacy instruction, I’m reminded of a broader question in policy journalism: How do you know things? What counts as good evidence?

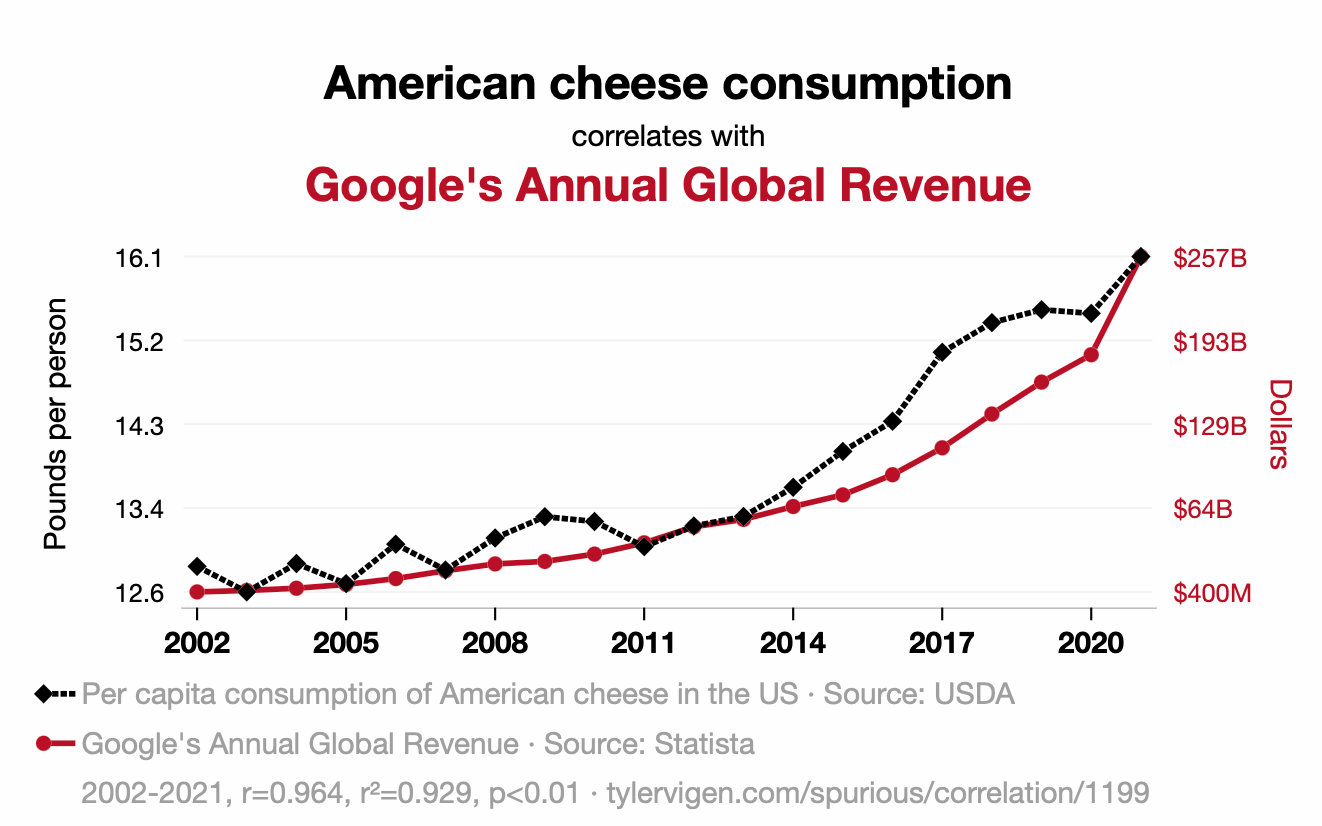

Sensible, informed, honest people understand that post hoc ergo propter hoc is a fallacy and that correlation is not causation. This chart is not good evidence that cheese consumption is driving Google’s revenue.

On the other hand, for policymaking purposes, it doesn’t make sense to demand absolute gold-standard evidence before making a policy change. There’s an old joke about how there are no randomized controlled trials showing that parachutes save lives when jumping out of an airplane.

But the larger issue is that sticking with the status quo is itself a policy choice.

If you’re a professor teaching quantitative social-science methods to undergraduates and you’re asked about smartphone bans in K-12 schools, I think the right answer is probably to say that the quality of the available empirical evidence on this is low. But if you’re the newly elected governor of New Jersey and you’re asked about a smartphone ban, I think you want to say that the weight of the empirical evidence suggests you should do it.

Similarly, I think it’s fine to say that the breadth of our experience with education policy reforms suggests that the Mississippi experience will turn out to be either overhyped, difficult to replicate at scale, or both.

And yet, if you’re the newly elected governor of a state whose early literacy scores have been dropping, you probably want to do something about that.

And since you definitely need to appoint someone to do K-12 policy jobs in your administration, I think it would be a pretty good idea to pick people who’ve worked in Mississippi or Louisiana or Tennessee or Alabama and have some plan to apply what’s worked in those states to your state. Just putting a huge thumb on the scale of the status quo until someone can devise a perfectly designed experiment doesn’t make a ton of sense.

Journalism and social science

These are issues that I wrestle with all the time in my work and that I’ve been wrestling with for a long time.

Social science isn’t new nor is the idea that public policy should be informed by evidence. But the idea that political journalism should be heavily informed by academic social science is relatively new, and I was part of the cohort of writers who pushed it into the mainstream in the mid-aughts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.