Capitalism needs honor and ethics

Don’t dedicate your life to scams, slop, and the exploitation of compulsion.

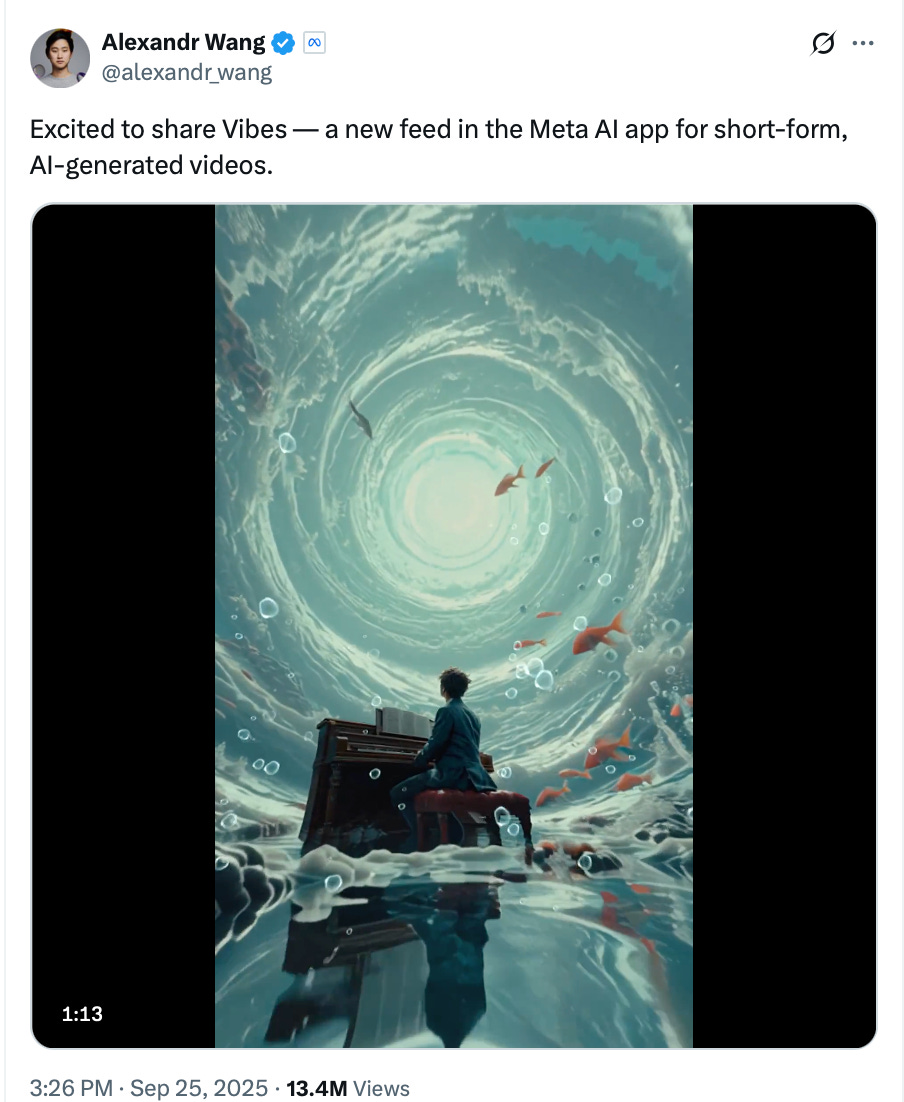

Last week, Meta’s chief A.I. officer was apparently excited to announce Vibes, a new product in which users can find themselves ensorcelled by A.I.-generated short-form video.

I don’t think it should be illegal to use A.I. to generate videos. And for fundamental free-speech reasons, we can’t make it illegal to create feeds and recommendation engines for short-form videos. Part of living in a free, technologically dynamic society is that a certain number of people are going to make money churning out low-quality content. And on some level, that’s fine.

But on another, equally important level, it’s really not fine.

Apple recently rolled out an A.I.-powered live translation feature for AirPods, which they claim will let users have a basically realtime conversation with someone who’s speaking another language. I’ve heard (perhaps unsurprisingly) that this is clunkier in practice than it appears in Apple’s demonstration videos. But simultaneous A.I. translation is a product that would be genuinely exciting. The translation space has seen significant A.I. innovation that has already transformed the business and may have important second-order benefits for the world. Super-cheap, super-fast translation should be helpful in many small-scale, non-lucrative areas, like making it easier for schools to communicate information to parents who don’t speak English.

Which is just to say that not all legitimate, legal commercial endeavors are equally worthy.

Adam Smith wrote famously that “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

Smith’s quip summarizes nicely the positive-sum nature of market exchange. But there’s a difference between earning your living by baking bread and earning your living by coming up with ad campaigns designed to induce heavier drinking among college students. There’s a difference between developing A.I. for drug discovery and developing A.I. to make compulsive short-form video. And I think that an important part of sustaining a liberal society and a market economy is regaining some form of judgmentalism about this kind of thing.

I think we all want to be part of a society in which people obtain social status by launching good businesses and good products that solve big problems and make the world a better place, not one in which anything that makes a buck is equally good.

The social responsibility of business

I think a lot about Milton Friedman’s famous 1970 essay, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.”

He was writing as one of the leading proponents of a right-wing course correction just after the apogee of 1960s left-wing politics. And in the piece, he’s pushing back against activist campaigns aimed at getting businesses to use quasi-voluntary action to tackle problems like racism and poverty. The view he’s putting forward, which makes a fair amount of sense, is that these campaigns are, in many respects, more like theft than like charity. An executive who hires a bunch of tough-to-employ cases from the community to do jobs that don’t generate revenue commensurate with their pay may seem like he’s being a nice guy. But it’s the shareholders’ company — does he have the right to do that? If he embezzled funds, everyone would see that as bad. Even if he embezzled the funds to do something sympathetic, like pay for his niece’s medical care or renovate a playground, there’s still an obvious problem with giving executives license to steal from the companies they are working for.

There’s also something a little short-sighted about praising my hypothetical executive. Yes, it’s nice for the people who get jobs. But there are a lot of people in the world who are poorer than they would like to be. Business profits don’t just vanish into thin air; money cycles through the economy in various ways. Capital is allocated to the places where it earns the highest return. This efficiency should ultimately make more people better-off than the alternative of allocating capital in inefficient ways that happen to help out the people who tugged on the heartstrings of tender-minded C.E.O.s.

This argument has been so influential because it makes a lot of sense.

But it has also, over time, served as a kind of universal acid that has eroded the very cultural values that were presupposed by Friedman’s essay.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.