Can Democrats Win Back the Working Class?

Four ways they can at least help stop the bleeding

This is a guest post from Jared Abbott, the Director of the Center for Working-Class Politics, and Fred DeVeaux, a PhD student at UCLA and researcher at the Center for Working-Class Politics.

Democrats have begun to recognize that they have a working-class problem, but it remains unclear how to solve it. We ran an experiment to find out (you can find the full report “Trump's Kryptonite” here).

Our results suggest that Democrats can reach working-class voters by running candidates from working-class backgrounds who center working-people in their campaign rhetoric, call out economic elites, focus on the need for more and better jobs, and distance themselves from the Democratic Party establishment.

Democrats’ biggest problem

No matter how you define it—by income, education level, occupation, self-identification—it is clear that Democrats have been losing the support of working-class voters since at least 2012, and likely much earlier.

Although most commentaries on the Democrats’ working-class problem have focused on working-class white voters, the last several election cycles suggest that Democrats have a working-class problem tout court. For instance, the progressive data analytics firm Catalist found Trump’s vote share among working-class (non-college) voters of color jumped six percentage points between 2016 and 2020, with both Black and especially Latino voters shifting toward Trump. Similarly, a comprehensive precinct-level analysis of 2020 voting patterns in high-Latino districts found that support for Trump in 2020 surged even in precincts with the highest number of Latino immigrants. These developments all challenge the widely-held notion that the US’s emerging majority-minority population will save the Democratic Party.

What’s more, Democrats’ woes with working-class voters extend far beyond the rural and small-town voters many pundits have placed at the center of this story. Indeed, recent analyses indicate that the party faces a “ticking time bomb” with urban working-class voters in key swing states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, where both turnout and Democratic vote shares in 2020 were down relative to 2012.

Our analysis of data from the Comparative Congressional Election Survey (CCES) and General Social Survey (GSS) survey shows similar trends. First, working-class disillusionment with the Democrats appears to have set in as early as the 1980s, with the percentage of working-class Americans (measured by occupation) who identified with the party falling from a high of around 65% in the 1970s to south of 40% by 2022. And since we find no comparable trend among middle/upper-class Americans—hose identification with the Democratic Party has fluctuated narrowly between the low and high 40s since the early 1980s—it seems this secular dealignment is a specifically working-class phenomenon.

We see a clear class divide open up in electoral terms beginning in 2012, with working-class voters (in this case measured by income and education) shifting slightly toward Romney and decisively toward Trump in 2016, as middle- and upper-class voters began their steady ascent in the opposite direction. By 2020, the class gap in support for Democrats had widened into a yawning gulf. And while the American working-class has been abandoning its historic home at the fastest rates in Red and Purple states, we see similar trends even in states where Democrats are dominant.

Can Democrats Afford to Abandon the Working Class?

Some argue that Democrats’ declining fortunes among the working-class may not be fatal, and may even help Democrats. Chuck Schumer’s once-questionable prediction, so they claim, has turned out to be right after all: For every blue-collar Democrat lost, the Party has picked up two suburban, high-income Republicans. Though Democrats have been losing working-class voters, they have made spectacular gains among college-graduates and higher-income voters. This, combined with efforts to minimize losses among the working class, delivered Joe Biden the presidency in 2020 and helped Democrats hold fairly firm in the 2022 midterms.

In turn, this argument goes, it is not clear that the Democrats’ tarnished reputation among working-class voters can ever be repaired, regardless of what Democrats do. Shortly after the 2020 election, Nate Cohn of The New York Times made a case for pessimism on that score that nicely encapsulates many Democrats’ uneasiness with a working-class focused electoral strategy. Cohn argued that the large-scale changes in class-voting we saw between 2012 to 2020 are “largely baked. The idea that Iowa’s going to lean blue again, or that Dems are going to win 60% in the Mahoning Valley [formerly industrialized Youngstown, Ohio], seems far-fetched.”

Democrats, Cohn concluded, are incapable of credibly making the bold economic pitch required to win these voters back, since deindustrialization and offshoring have effectively put a cap on the level of job creation that’s actually reasonable. And even if Democrats did shift to such an approach—which looks increasingly unlikely as their electoral coalition becomes more upscale—Republican support among working-class voters would be difficult to dislodge in the face of pervasive culture war fights.

But without at least maintaining their current share of the working-class voters (a dubious prospect given recent trends), Democrats’ chances of winning the presidency and securing a stable majority in Congress are small indeed. The structure of the US political system—especially the electoral college and the US Senate—is inherently biased toward battleground states where working-class voters are a majority of the electorate, and, equally important, where there are not enough persuadable middle-class voters to compensate for Democratic losses among working-class voters. As William Galston and Elaine Kamarck explain, in four of the five battleground states carried by Biden but lost by Clinton in 2016 (Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Arizona), working-class white (non-college) voters alone outnumbered the size of the white college-educated, black, and Latino votes put together. Since Democrats have no chance of maintaining regular control of the Senate without winning these states, they simply cannot afford to lose the working class.

Yet according to Schumer’s logic, the size of the working class isn’t necessarily the deciding factor. As long as Democrats can make larger gains among middle and upper middle class voters than they lose among working-class voters, a strategy focused on highly educated voters could still secure Democratic victories in battleground states.

In practice, though, this logic runs into a major obstacle: the vast majority of swing voters in battleground states are blue-collar, not middle-class voters. According to data from the American National Election Survey (ANES), of the battleground state voters who switched parties between 2016 to 2020, nearly three quarters (72%) were non-college graduates. With these numbers, if Democrats followed Chuck Schumer’s advice and focused on a strategy to trade blue-collar for middle-class suburban voters, they would virtually ensure Republican victory. Rather than picking up two middle-class voters for every one working-class voter they lost, Democrats would sacrifice three working-class voters for every middle-class voter they picked up.

Democrats could conceivably make up for the loss of working-class voters by boosting turnout among middle and upper-class voters. But the working-class’s share of the 2020 electorate was 24 percentage points larger (62% to 38%) than that of its middle and upper-class counterparts, and there is little indication that turnout rates among middle and upper-class voters are likely to rise any faster than those of working-class voters in the foreseeable future. So this also seems like an unlikely strategy for success.

Crucially, however, even if Democrats were able to hang on to power by winning over more wealthy and highly educated voters, their victory would be a hollow one. A Democratic coalition increasingly reliant on affluent voters and donors would severely limit the party’s capacity to implement the transformative economic reforms needed to lift millions out of poverty and ensure a habitable planet, for starters. This is because, regardless of party, upper-class voters are less likely to support important forms of economic redistribution than their working-class counterparts.

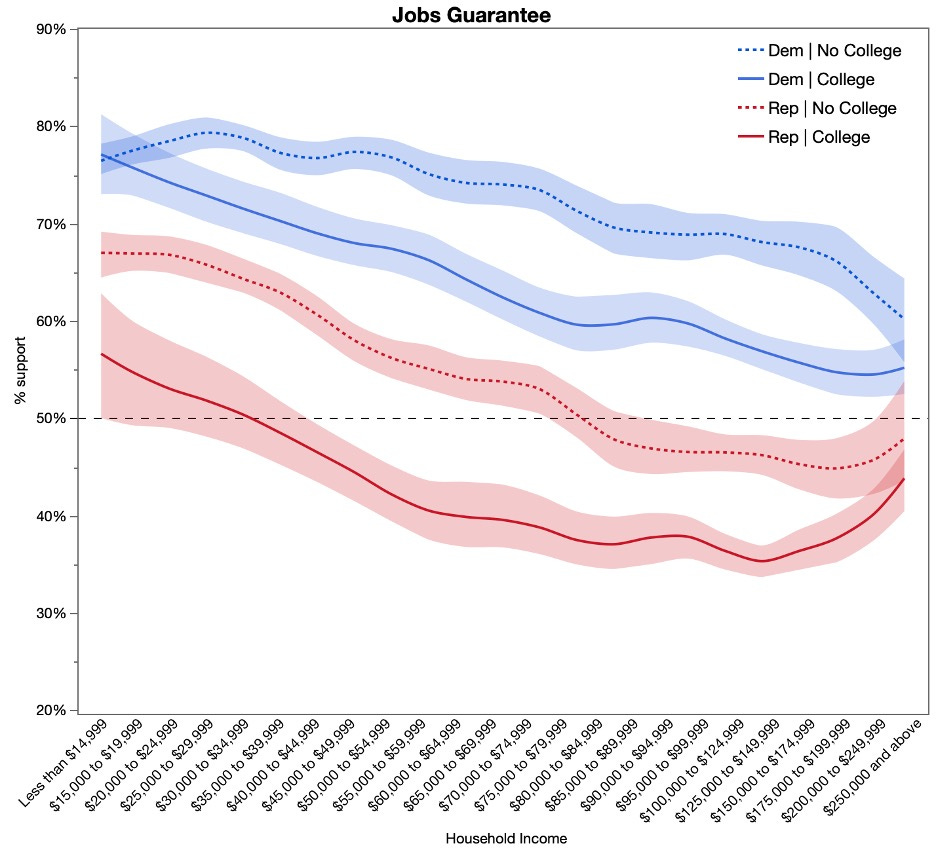

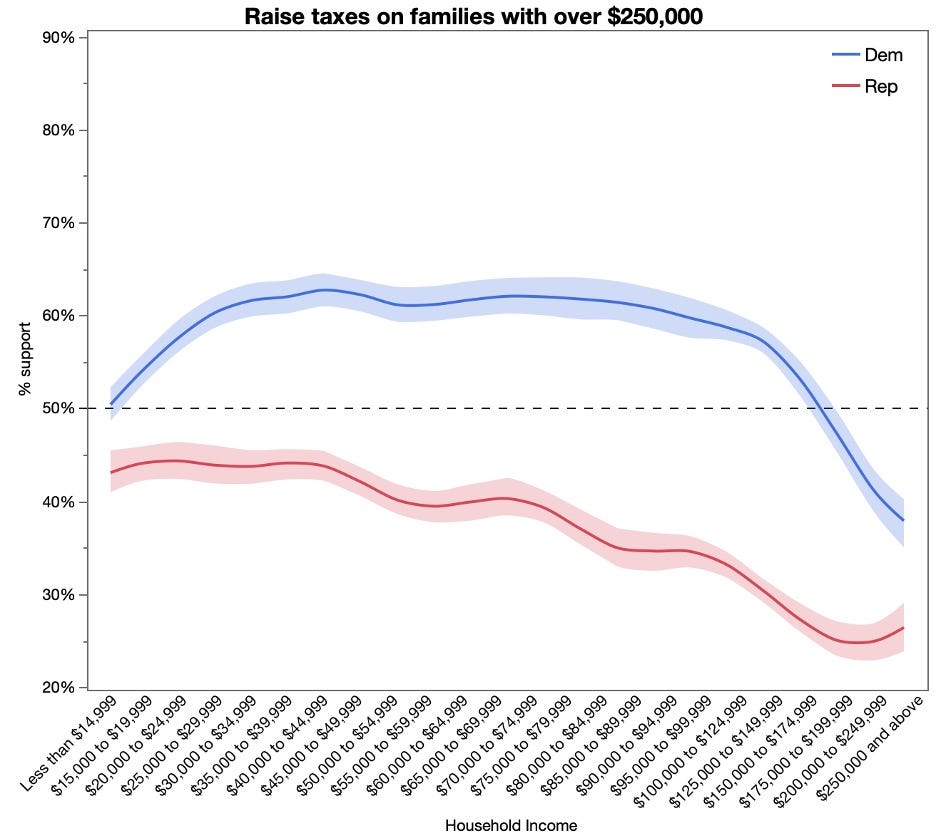

Indeed, not only are working-class Republicans far more supportive of economic redistribution than wealthier Republicans, but when it comes to certain key progressive issues like a jobs guarantee or raising taxes on incomes $250,000 and above, working-class Republicans are even more supportive of economic redistribution than wealthy Democrats. A Republican voter without a college degree making $40k a year, for instance, is nearly twice as likely to support a jobs guarantee than a college-educated Republican making over $80k, and nearly 10 percentage points more likely than a college-educated Democrat making over $80k. Put differently, wealthier Republicans are the last group that Democrats should want to bring into their coalition, especially if they come at the expense of working-class voters.

In short, losing working-class voters means losing them to right-wing populism, while turning the Democrats into a party of rich elites—a political coalition unwilling to get behind real economic redistribution.

Bringing Workers Back to the Democratic Party

So how can Democrats appeal more effectively to working-class voters?

We asked 1,650 Americans to evaluate pairs of hypothetical Democratic candidates. Each candidate was randomly assigned demographic attributes, such as race, gender, and previous occupation, as well as policy positions and a rhetorical style. After comparing each pair, respondents reported which one they preferred. We limited our analysis to focus only on voters who do not describe themselves as “strong partisans,” and therefore are most likely to change their voting behavior from one year to the next and play a pivotal role in deciding elections.

Our results indicate that Democratic candidates can do four things to appeal to working-class voters across the political spectrum.

Run working-class candidates. All else equal, working-class voters prefer candidates from non-elite, working-class occupations (middle school teachers, construction workers, nurses, and warehouse workers) over those from elite, upper-class occupations (corporate executives, lawyers, and doctors).

Focus on messages that champion the working class and critique economic elites. We found that working-class voters prefer candidates who say they will serve the interests of the working class and who place blame for the problems facing working Americans on the shoulders of economic elites. In results we do not show here, we find that this economic populist message is particularly effective among working-class respondents who work in manual jobs, a group that Democrats increasingly struggle to reach.

Run on a jobs-first program. Working-class voters viewed more favorably candidates who highlighted a progressive federal jobs guarantee rather than one of the moderate economic policies we included in the survey (a small tax increase on the rich, a $15 minimum wage, and a jobs training program through small businesses). And this result was not limited to working-class Democrats. Indeed, the only policy we tested that was viewed positively by working-class respondents across the political spectrum was the progressive federal jobs guarantee—though working-class Republicans were slightly more favorable toward candidates who ran on the moderate job training program. Candidates who centered jobs were also favored by a range of other key constituencies from whom Democrats need to maintain or improve support, including African Americans, recent swing voters, low-engagement voters, non-college voters, and rural voters. Unfortunately, however, in our analysis of 2022 Democratic television ads, we found that just 18% even mentioned jobs.

Take a critical stance towards both parties. Candidates who explicitly criticized the Democratic and Republican Parties for being out of touch with working- and middle-class Americans were viewed more favorably across the board compared to candidates who either said nothing or stressed that Democrats have delivered for working- and middle-class Americans (proud Democrat in the graphic below). Importantly, these results are not simply driven by voters who lean Republican, but also Independents and those who lean Democrat.

Working-class voters may find economic populist working-class candidates appealing, but does any of that matter once they hear candidates’ views on social and cultural issues? In our experiment, we did indeed find that social issues—specially immigration—had a larger impact on working-class voters’ candidate preferences than economic issues.

However, working-class respondents were no more conservative on social issues than middle- or upper-class respondents, so there is little reason to think Democrats can only reach working-class voters by alienating socially-liberal college graduates in their coalition. While most voters preferred Democratic candidates who ran on moderate rather than progressive social policies, their views on social issues largely divided voters along partisan rather than class lines. That is, potentially divisive social issues are no more of a liability for Democrats among working-class voters than they are among middle- or upper-class voters.

In addition, respondents’ reactions to candidates varied widely across social issues, meaning that the degree to which social or cultural issues blunt the impact of economic populism depends heavily on the issue at hand and messaging approach around that issue. That said, as we have shown in other work, they should be careful to present their policies in a way that is relatable to working-class voters.

Democrats need not, and should not compromise on progressive social issues, and were right to highlight Republicans’ backward positions on abortion in their midterm campaigns. But overall, if Democrats want to stop bleeding working-class voters—and indeed, win many of them back—then they need to run campaigns that appeal to working-class voters. That means running candidates from working-class backgrounds who call out economic elites, center a jobs-first agenda, and critique the Democratic and Republican Party establishments for being out of touch with ordinary Americans.

If Democrats shy away from the working class, they risk losing the left's key constituency to right-wing populism. A Democratic coalition that includes the working class is the only kind of coalition that can deliver historic gains to working Americans and carry out the social and economic changes that ordinary Americans so desperately need. Working-class politics is the only viable path forward for a democratic and humane future.

"Although most commentaries on the Democrats’ working-class problem have focused on working-class white voters, the last several election cycles suggest that Democrats have a working-class problem tout court."

The use of "tout court" here elevates this to the Hall of Fame level of self-parody. If it was intentional, then I congratulate the authors on their comedy-writing chops.

In DougJ's frame, this would go, "At Dolly's Diner in this abandoned mill town, working-class patrons are divided over whether "tout court" or "sans phrase" does a better job of capturing the flavor of "uberhaupt". But they all agree that they love the flavor of Dolly's apple pies."

First, good essay and very helpful in terms of exploring the set of messages that can help win back what used to be the core constituency of the Party.

Did your analysis explore WHY the Republicans have picked up votes in this area? Polling test questions is good, but I think it has proven less predictive than we'd all like. We know the working class agrees with Dems on specific economic questions, but the losses have continued. What positions did Republicans take that attract, or that Democrats take that repel?