Blue state Republicans are the problem

When it comes to housing reform in the Northeast, right-NIMBYs are quiet online but loud in state legislatures.

We’ve got two new local Slow Boring events on the calendar! Thanks to Thomas for organizing a meet-up in Salt Lake City on June 25 and to Casey for putting together a happy hour during YIMBY Town 2025 on September 15. Details and links to register on the Events page.

Last week, Scott Wiener’s SB-79 creating mandatory upzoning near mass transit stops passed the California state senate by a 21-13 margin.

That’s not the end of the story for this legislation, but people in California who track this closely say that the senate was likely the toughest hurdle to clear and that the assembly and the governor will be easier. This is a really big deal for a state that, despite its reputation, has actually invested a lot in building out mass transit systems over the past generation, but where few places outside of the Bay Area have the land use patterns to support ridership.

Importantly, for procedural reasons, this bill needed 21 votes to pass — a bare majority would not have been good enough — and it drew a lot of opposition from Democrats representing Greater Los Angeles. So even though the bill’s lead author was a Democrat and its main proponents are Democrats, it only passed because Republicans like Megan Dahle (from the rural northeast of the state), Shannon Grove (from Bakersfield), and Rosilicie Ochoa Bogh (from the eastern part of the Inland Empire) voted for the bill. Plenty of Republicans joined the NIMBY Democrats in voting no. But it was a bipartisan bill, and it passed because it was a bipartisan bill.

And bipartisanship in housing reform matters beyond the vote count.

There’s been a lot of discourse recently about the political appeal (or lack thereof) of “abundance” ideas, but I think a key real world factor is that bipartisanship is good politics. A governor who signs a pro-growth, bipartisan, commonsense regulatory reform bill is burnishing his image in the eyes of swing voters and setting himself up for upward mobility. Signing a bill that splits your own party while uniting the opposition, by contrast, is risky. Over in Connecticut, for example, a big zoning reform bill also recently passed — House Bill 5002 — but this one met with unanimous GOP opposition, plus a few Democratic defections. The blunt fact that this is a partisan bill makes it politically dicier than the California one.

This question — the attitudes of blue state Republicans — is in my view the underrated dark matter of American housing politics.

Republicans have led several major pushes for housing reform in red states. These efforts are inevitably GOP-led because these states have GOP-controlled legislatures, and to the best of my knowledge, none of them have met with uniform GOP opposition. But in New York and Maryland, we’ve seen divided Democrats unable to push through housing reforms supported by Democratic governors in the face of relentless GOP hostility.

You may hear “blue state problems” and think “problems with Democrats,” but outside of Hawaii, what the Republicans in blue states do really matters.

The NIMBY right

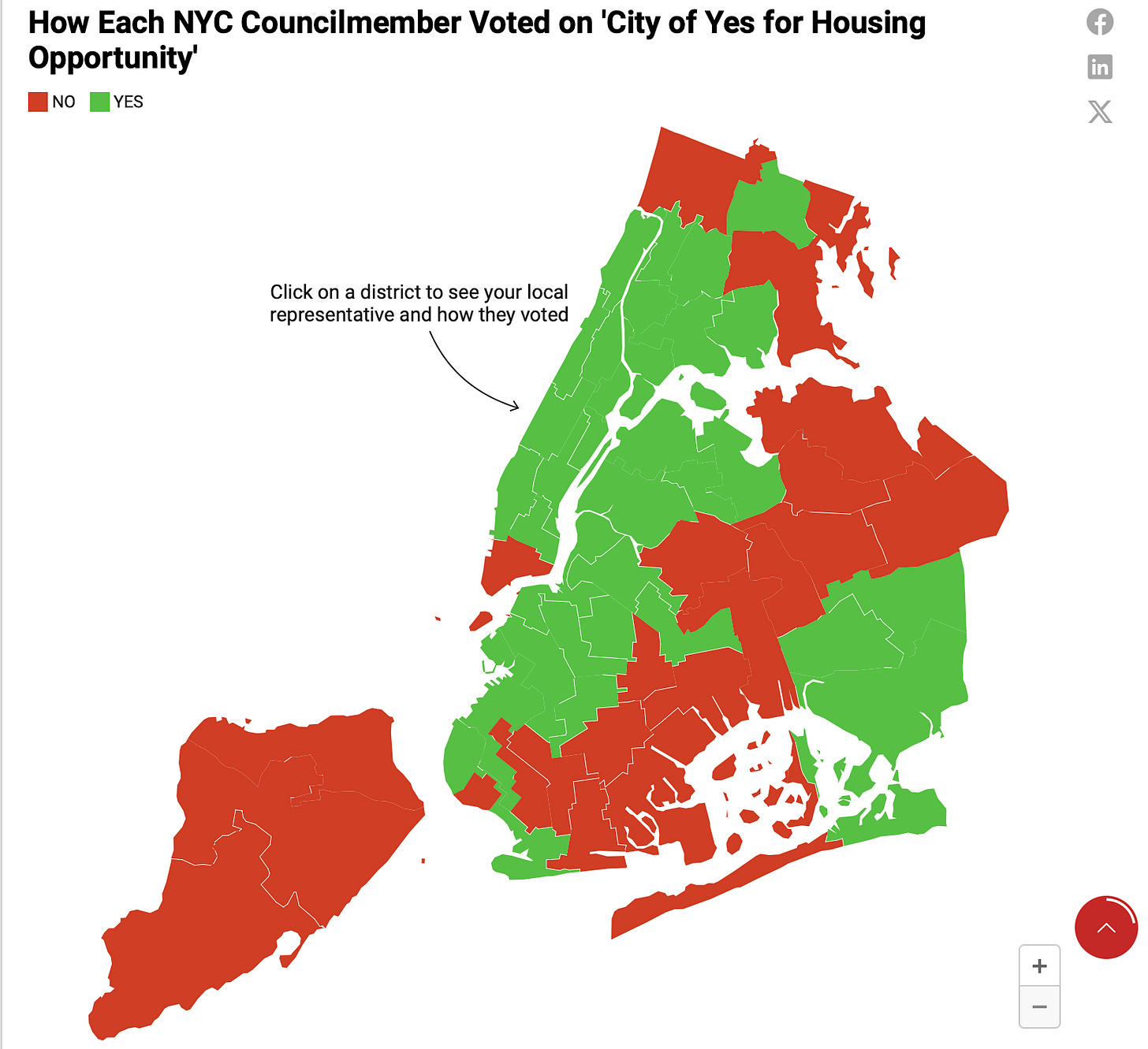

There are only five Republicans on the New York City Council, but they all voted “no” on the City of Yes zoning initiative last December. What’s more, a lot of the “no”-voting Democrats on the council were people like Kamillah Hanks from northern Staten Island, who could plausibly lose an election to a Republican.

Left-NIMBYism has an extremely vocal presence on the internet, where people care a lot about relative status and agenda control. And it has a non-trivial voice in real world politics, as you can see in the career of Henry Stern a “climate change attorney turned California State Senator,” according to his Twitter bio, who consistently votes against transit-oriented zoning bills in the legislature.

But right-NIMBYism is also a powerful force, both in blue state suburbs and in quasi-suburban peripheral neighborhoods of big cities like New York.

This school of thought doesn’t have much of a voice on the internet, though, in part because it’s a politics of cranky old people who aren’t especially online. But also I think it’s in large part because it’s pretty literally NIMBYism. Zoning reform opponents in southern Staten Island don’t have some kind of galaxy brain take about the nature of housing and the economy — they just literally do not want their neighborhood to change and don’t necessarily have long-winded essays or critical geography papers about why that is.

Indeed, to the extent that right-NIMBYs in the northeast speak about their views at all, they tend to misstate the issue, because being Republicans, they don’t want to admit that they’re arguing for stricter regulations.

When New Jersey governor Phil Murphy suggested some kind of statewide zoning reform, for example, Tony Bucco, the GOP leader in the state senate, said, “I think the devil will be in the details. If they’re just going to impose zoning requirements, then no, I don’t see that.”

In other words, he talked as if Murphy was proposing to put more stringent economic regulation in place, in which case you would obviously expect Republicans to be opposed. But what’s being “imposed” here is a reduction in regulation. Similarly, in Maine, where the state’s Democratic governor has been looking at various housing reforms, the local free market think tank denounced any effort at subsidizing affordable housing on the grounds that the real problem is overregulation, but also stated that they oppose anything that would undermine “local autonomy.” Here, again, to square the circle rhetorically, they said that “state intervention risks undermining property rights, local decision-making, and market-driven solutions to housing challenges.”

But the actual thing happening is that local decision-making undermines property rights and market-driven solutions.

New construction has both costs and benefits, and the benefits are larger than the costs. But the costs (more traffic, less parking, crowding at local schools or parks) tend to be localized while the benefits of a more dynamic economy are broadly spread. That’s why most new housing in the United States is built in unincorporated areas where there is no local authority to block it, and it’s why New England, which has almost no unincorporated land, has the most severe housing shortages.

When Republicans love to preempt

In red states, meanwhile, Republicans are temperamentally much less inclined to favor local control.

Big cities everywhere are full of Democrats who like to implement various kinds of business regulation. And a perennial favorite activity of GOP-controlled state legislatures in places like Tennessee, Texas, and Georgia is passing laws to preempt local efforts to raise the minimum wage or otherwise lib out.

Preempting local zoning rules is a different kettle of fish, but it’s a broadly similar-looking kettle, and as a result, Republicans are open to the argument that they should do zoning preemptions. This spring, Texas passed a big zoning reform, SB 840, that will allow apartment buildings and mixed-use projects by right across all land that is currently zoned for commercial purposes.

One downside of “strip malls into apartments” land use reforms is that they kind of concentrate lower income families into the highest-traffic, noisiest, most polluted parts of your city. But it is still much better than giving those families nowhere to live at all. And I get why it strikes some people as a politically safe form of infill, because the new apartments aren’t intruding into single-family neighborhoods.

What’s weird about SB 840, though, is that it applies only to cities with over 150,000 residents that are located in counties with over 300,000 residents. This is an odd conceptual gerrymander that ensures local autonomy will continue to be respected across almost all the suburbs of Texas’s major cities, and also for small cities like Lubbock (population 270,000) and Laredo (population 260,000). Instead of a broad statewide measure, it specifically targets the major cities of Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, Austin, and El Paso, and it also hits a whole bunch of suburban communities in the DFW metroplex (Arlington, Plano, Irving, Garland, Frisco, McKinney, Grand Prairie).

Don’t get me wrong! Even though I think this structure is ridiculous, I would vote for the bill anyway. I believe it will generate a lot of infill housing, some of it in genuinely desirable areas, and be good for the state.

And that’s basically how it passed.

Not only did it get overwhelming support from Republicans, it was backed by a 6-4 margin among Democrats. In Montana, where there’s been a strong cross-party pro-housing bloc in the state legislature for a few years now, Republican Katie Zolnikov has a bill that would basically exempt all multifamily housing from local parking requirements — but only in the state’s 10 largest cities. There’s no principled reason for doing it this way that I can think of. But this sort of limitation in applicability means that red state land use reform has a bit of a lib-owning quality that helps make it appealing to Republicans.

Conversely, in blue states, Republicans are accustomed to thinking of the state government as the enemy and tend to fight tooth and nail for local control, even though it defies their official analysis of the states as over-regulated and too hostile to business.

Constructive blue state conservatism would help

This is why I’m a little annoyed by the potshots aimed at Abundance Democrats by the Manhattan Institute.

It’s not that I think the points Reihan Salam is making in this article or Charles Lehman is making in this article (or that I’ve seen them and their colleagues make on Twitter) are all completely wrong. But I do think that they are more or less completely ignoring the fact that the attitudes of blue state Republicans are actually an important driver of the dysfunctional dynamics that we all agree are bad.

Or maybe to put it more positively, I am really glad that several rural Republicans in California rode to the rescue of Wiener’s transit-oriented development bill.

You could easily imagine a world in which they instead decided to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the NIMBYs from the LA suburbs and engage in obfuscatory rhetoric about local control. Their constituents in rural California, after all, are almost certainly not enthusiastic about ideas like urban infill and boosting transit ridership. It would be easy to come up with reasons to vote no. Precisely because it’s a blue state whose legislative leaders are all pretty progressive, the bill’s authors have structured a deregulatory initiative to align with progressive values rather than the values of rural California. But senators Dahle, Grove, and Bogh looked beyond the vibes to see pro-growth deregulatory legislation that objectively serves the interests of their constituents and aligns with conservative policy analysis and voted for it.

If the state legislatures in New York and Maryland and New Jersey had blocs of Republicans like that, they could pass some bills and get things done. In Connecticut and Maine, they could probably pass bolder legislation.

I get that blue state land use reform is not necessarily pitched in a rhetorical mode optimized to secure Republican support.

The main Connecticut YIMBY group is called Desegregate Connecticut, which is a name that seems aimed at Yale professors rather than suburban Republicans. But it’s important to be pragmatic and, at times, meta-pragmatic. The way the Texas bill is structured offends my sensibilities, but it’s also just clearly the case that in a red state, anything that happens is going to be primarily geared toward Republican sensibilities. On the list of things Texas Republicans could possibly do, forcing Texas cities and some of the Dallas suburbs to upzone is pretty good. I’m glad most of the Democrats in the legislature voted for it, and I wish that more did.

The Northeast needs a better housing debate

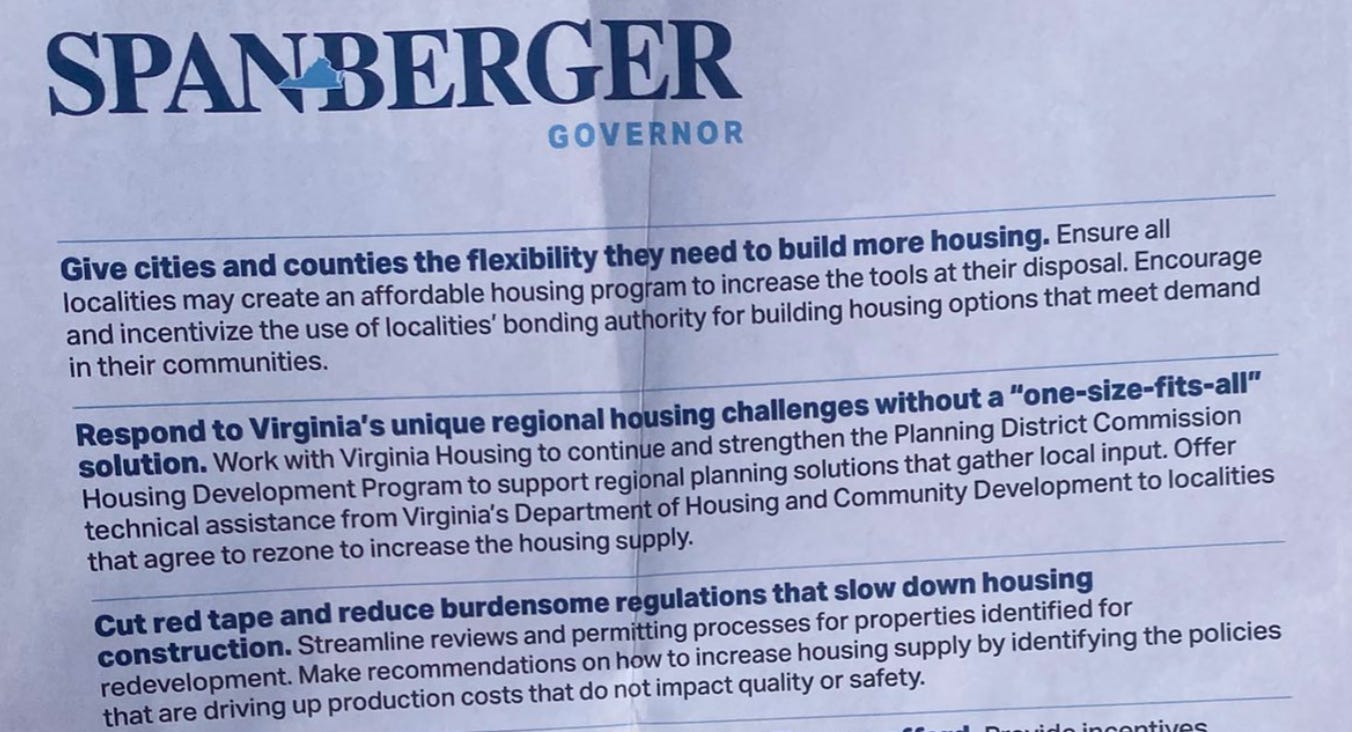

Abigail Spanberger, the moderate House Democrat running for governor of Virginia, recently released her plan to lower the state’s housing costs if she wins in November.

At the level of abstract rhetorical analysis, it’s good. She understands the need for supply, and front loads the idea that delivering more supply involves regulatory reforms. But the actual proposals are extremely weak tea. She wants local governments to want to rezone, but doesn’t want to make them. I get the need for political pragmatism on housing as on other things, but this is a level of pragmatism that ensures very little will change, and we shouldn’t kid ourselves about that.

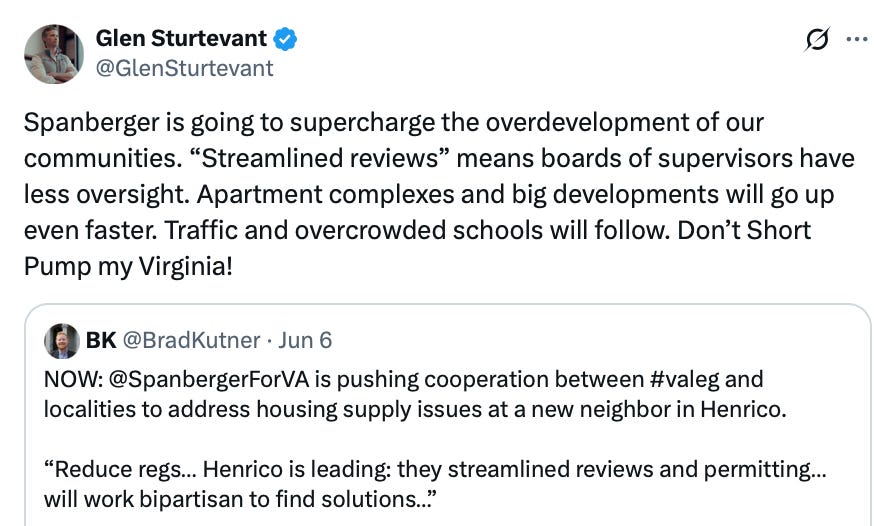

And yet the outraged response from Glen Sturtevant, a young up and coming Republican in the state senate, makes it sound like she’s putting forward a visionary statewide deregulation plan that would unleash incredible levels of growth. I wish he were right!

I don’t think Sturtevant’s bad tweet gets Spanberger off the hook for failing to meet the moment. But it is illustrative of the problematic dynamics we’re dealing with here in the northeast.

Neither the local Republican parties nor the local business communities that they’re responsive to are particularly interested in promoting pro-growth regulatory reforms. To some extent, they’re trapped in their own suburban identity politics. But in the California case, rural Republicans ultimately got to yes on a transit-oriented zoning preemption that simply won’t impact their constituents. And in Texas, Republicans cooked up a form of zoning preemption that didn’t preempt the jurisdictions they care about personally. There are creative ways to generate proposals that make an impact while also being limited.

And if cautious politicians like Spanberger (or Janet Mills in Maine, or Ned Lamont in Connecticut) were being challenged to do more to address the northeast’s over regulated housing markets rather than less, we could actually accomplish something useful.

“ This school of thought doesn’t have much of a voice on the internet, though, in part because it’s a politics of cranky old people who aren’t especially online.”

May I introduce you to Nextdoor?

And here I am in Boise, where the city officials here took it upon themselves to rewrite their own zoning code, which allows by right ADUs almost everywhere, (du/tri/quad)plexes in the grand majority of residential land, up to four stories on most parcels, and my favorite: completely abolished commercial zoning and replaced it with mixed used zoning so that any retail or office space can also by right add housing on the lot...while meanwhile, the city is being utterly repressed by a zillion evil state preemption measures imposed by people who, live far, far away from Boise and have little in common other than being lumped in together via arbitrarily drawn borders from more than a century ago.

And since Matt is curious about the "greater than # residents" provisions, the purpose is very much to keep urban centers down and powerless, because of rural resentment and fear over urban areas doing the same, even though whatever laws the cities pass wouldn't impact each other! "Greater than 100,000" has been used for many years just to specifically target Boise, and now that some of the suburbs ans Coeur d'Alene are surpassing that, I'm guessing they'll change all of that to 250,000 some day. This should be an Equal Protection Clause violation. Just evil, evil stuff.