Biden's media problem

An industry full of young, educated, urban progressives is a mixed blessing at best

The people who produce the news are primarily young college graduates living in big cities, a demographic that skews way to the left of the electorate. And the audience for this news, though less ideologically skewed than the producers, is still significantly to the left of center.

That dynamic is a powerful force multiplier for platforming and disseminating new left-wing ideas, including ideas that go from edgy to dominant — like “gay couples should be allowed to get married” — as well as ideas that provoke massive backlash the minute they get any purchase — “maybe cities don’t need police departments.” It’s a major structural feature of the media landscape that helps explain why the general policy trajectory over the past generation has been toward the left.

But electorally, it’s a decidedly mixed bag, since the journalists, though clearly on the left ideologically, aren’t partisan propagandists.

In fact, precisely because their left-of-center ideas appeal to the left-of-center audience, more or less nonpartisan journalism tends to crowd out the potential marketplace for partisan propaganda on the left. But beyond that, the ideological skew really is downstream of demographic factors. The media is on the left, but that doesn’t mean the media heavily represents the views of Hispanic SEIU members or elderly churchgoing Black women. Young, educated urbanites are a very Democratic demographic group, but they’re not typical of Democratic voters, much less of the public as a whole.

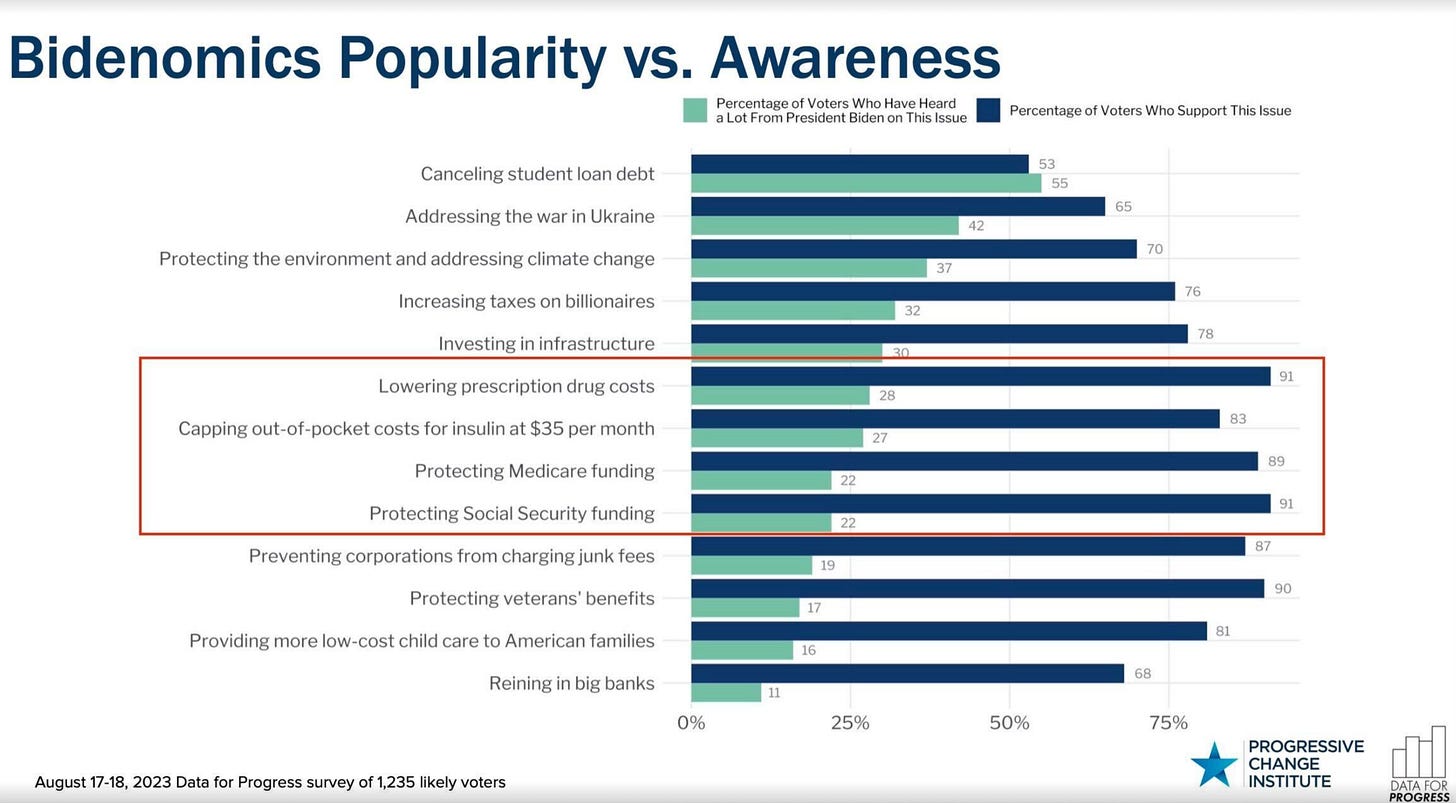

That partly explains findings like this one, where the Biden policies people feel they’ve heard the most about — student loans and Ukraine — aren’t his most popular ones:

Some of that is arguably flawed messaging from the White House — I think Biden’s team tweets too much about student loans, and the president seems more personally interested in the details of foreign policy than domestic issues. But it’s largely a media effect. The people who make (and, to a lesser extent, the people who consume) journalism are very interested in the student loan issue and not as interested in the Medicare stuff. But the voters care a lot about Medicare, and if they viewed the 2024 election as a referendum on Joe Biden’s approach to Medicare versus Trump’s promise to repeal these planks, that would be a huge boost to Biden.

Unfortunately for the president, his actual Medicare policies have played essentially no role in the public’s understanding of contemporary politics.

Student loan coverage dominates Medicare

The Biden administration has done four big things related to Medicare and prescription drugs:

Capped the price of insulin at $35/month

Negotiated down the price of 10 major prescription drugs

Capped annual out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs

Implemented a tax to discourage companies from raising prescription drug prices

They’ve also undertaken a number of student loan forgiveness initiatives. And both sets of initiatives have been covered in a range of media outlets, but the people who feel like they’ve heard way more about student loans aren’t mistaken — virtually every outlet dedicates dramatically more coverage to student loan policy than to prescription drugs.

And though you wouldn’t know this from listening to people talk about politics on Twitter, a much larger share of the population has Medicare benefits than student loan debt (18 percent vs 12 percent). And almost everyone will get Medicare at some point in their lives, which is certainly not true for student loans.

To be fair, some of this falls out of structural differences between the issues.

Biden’s multi-pronged Medicare policy is a set of provisions that were all rolled together in the Inflation Reduction Act, which also included a ton of climate provisions. His student loan policies, by contrast, were announced individually as the Education Department has rolled out a bunch of different initiatives.

I also think conservative media exercises strategic message discipline in the way that they talk about Biden. Fox News runs plenty of criticisms of Biden. But they don’t run segments talking about how senior citizens are now living high on the hog thanks to his improved generosity of Medicare benefits. Even though conservatives don’t like these ideas and have promised to repeal them, conservative media limits their criticism to more controversial Biden initiatives, like electric cars, which results in more discourse from both sides about Biden’s less popular ideas relative to his more popular ones.

So there are structural reasons the coverage has shaken out this way. But those reasons aren’t totally unrelated to the fact that the media fundamentally finds the student loan topic more interesting.

Picking fights

Young media progressives were intensely-but-sporadically interested in health care policy when it was linked to Bernie Sanders and a sweeping vision of Medicare for All. Which is just to say they have a kind of hazy ideological interest in the subject more than a practical interest in the year-in, year-out grind of incremental policy change. It served for a time as a signifier of intra-party factional positioning, but the issue was displaced by police defunding and then later by Palestine. But again, it’s precisely because something like prescription drug policy isn’t a factional signifier that it would be good for Biden if it was covered more.

Democrats healthcare ideas are not just popular, they’re also ideas that Joe Manchin and Bernie Sanders agree on.

They might disagree about how much further you’d ideally take these ideas. But insofar as the topic of conversation is the Chamber of Commerce trying to get the Supreme Court to toss this stuff and Donald Trump promising to repeal it, the issue unifies Democrats and divides rank-and-file Republicans from their party leaders.

Again, though, it’s precisely because the media tends to be left-wing that the media tends to focus on ideas that divide Democrats rather than ideas that unite them. The factional infighting is something that journalists think is intellectually interesting and that their readers like to read about. Years ago, when the federal minimum wage was $7.25 and some Democrats wanted to raise it to $15, the “Fight for Fifteen” got a lot of coverage. More recently, $15/hour became something like a party consensus position, at which point coverage of it vanished.

But the federal minimum wage is still only $7.25/hour. If Democrats were to recapture the House and secure a Sinema-proof Senate majority in 2025, it would likely get raised. But nobody is talking about that precisely because it no longer has interesting factional stakes.

Bad vibes and trouble

A point I tried to make on our Politix episode with Will Stancil is that progressive-minded people — and particularly progressive-minded media figures — have a certain ideological investment in the promotion of bad vibes.

Younger left-wing people are notably more depressed than politically conservative ones, which may be partially selection effect, but I think is driven by the fact that so much progressive messaging about the world is marked by negativity and doomerism. I read a cool story last week out of the Bay Area about how BART brought engineering work for new rolling stock in-house, which wound up delivering the trains under budget and ahead of schedule. That’s an upbeat, positive news story that’s also straightforwardly left-wing in its implications. But that’s not the kind of narrative that gets traction in progressive media spaces, which are dominated by pronouncements about how we live in a late capitalist dystopian hellscape.

I think that realistically, if you ask an average person to articulate their doubts about left politics, it’s probably not that they need to be convinced the status quo is a hellscape; rather, they think that if they empower progressives to raise taxes, progressives are just going to waste a bunch of money rather than deliver anything useful.

News like the BART officials coming up with ways to spend money more efficiently and make things work better would actually help alleviate doubts and concerns. Or to get back to health care, health care is a topic where most people are broadly sympathetic to the Democratic Party’s values and think the free market idea that if you’re poor you should just get sick and die untreated is insane. So they might be interested to know that years of incremental reforms from Democrats have succeeded in driving the uninsurance rate down to the lowest-ever level. And note that this 8.6 percent figure includes people living in the country illegally, which is not a great situation, but that’s really much more of an immigration policy issue than a health care policy issue.

But it’s considered both un-progressive and un-journalistic to talk about good things rather than to expose problems.

These impulses align with partisan imperatives as long as there’s a Republican in the White House. But if all we talk about is how awful everything is during a Democratic Party presidency, we’re ensuring that any Democratic incumbent will be swimming against the current.

You don’t need a weatherman

This nexus between left-wing politics and doomerism is, I think, particularly problematic for Democrats in an era when the party has put so much effort into combatting climate change. The IRA’s climate provisions aren’t perfect, but they are a very smart and well-designed compromise between Democratic leaders’ belief that it’s very important to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the public’s view that they are not so interested in this problem. And as long as you can avoid massive backlash, which Democrats have, it’s fine to do things that most voters don’t care about.

But you’d ideally want the people who do care about the issue to be really happy with you.

And why shouldn’t they be? American climate emissions are at their lowest level since 1991, the trend toward lower emissions has accelerated thanks to Biden’s policies, and contrary to the haters, the overall American economy has continued to grow at a nice clip.

But it’s considered un-progressive to emphasis this kind of positive news about emissions. Year-end climate coverage was dominated not by the news that US emissions are down below their pre-pandemic level, even as the economy has grown, but by the fact that 2023 was the hottest year on record.

These are both true stories, and there’s nothing wrong with reporting both of them.

But one story — the climate doom narrative — is considered progressive to emphasize. The other — the narrative about how Biden’s policies are succeeding — is the one that, if emphasized, is likely to help Democrats win elections, which will continue to drive emissions lower. After all, it’s not Joe Biden’s fault that China continues to build coal plants. China has also engaged in massive deployments of nuclear and renewables, and they’re ahead of us in electric cars, so there is some reason to hope their emissions will start falling soon. But if you want to know why global emissions aren’t falling now, it isn’t any shortcoming of American public policy. American climate policy is succeeding and people ought to know that.

Meanwhile, it continues to be the case that far too many of the people who care about climate change don’t realize that the RCP 8.5 doomsday scenarios are now considered very unlikely to occur. That doesn’t mean there’s no problem here. But losing a finger is a much smaller problem than losing a whole arm or your head, and if you were facing all of those possible outcomes, you’d want to know which it is. I keep seeing jokes on TikTok about how there’s no need to save for retirement because of climate change, and that’s just not true.

Be the change

To an extent these are just observations.

Conservatives find it annoying that American journalists are so left-wing. But in practice, this generates a much more complicated partisan landscape than you might think. The conservative audience is alienated by the values of mainstream journalism and spends a lot of time consuming propaganda news that is optimized for partisan purposes. The progressive audience finds mainstream journalism congenial enough that it’s hard to compete with, and yet, mainstream journalism produces a steady stream of negativity and ultra-specific focus on the idiosyncratic problems of young urban professionals.

But media outlets are also trying to make money.

Here’s a USA Today story about a new federal rule to force insurance companies to stop dragging their feet in deciding whether to approve new prescriptions or procedures. I have not seen a lot of coverage or discussion of this story, which is a typical “important but in a slightly dull way, mostly to older people” story that could be meaningful to a lot of voters but doesn’t get media attention. But if you all click on and share the story — on X, on Facebook, on LinkedIn, whatever — it will get more attention. If everyone ignores it, it won’t. At the end of the day, it’s as simple as that.

No quibbles with the column, but the bigger problem with over-hiring from this cohort is the lack of subject matter expertise. They have a lot of ideological commitments, high confidence, and very little knowledge. So they fill in the gaps with their assumptions or repeat the conventional wisdom in their newsroom.

Example: an Army friend was complaining to me the other day about crappy coverage of military topics. I saw an analysis showing that less than 0.5% of NYT staffers have any military background, and those people mostly work on the tech side. So it’s not surprising that they’d make errors of fact and analysis. But why? The military has trained journalists that the NYT could hire from.

And for the love of God, foreign correspondents should speak the language. At a minimum, they should be able to have a basic conversation on the street. If they can’t even communicate, who knows what cultural assumptions or biased filters are showing up in their work. Imagine trying to report on the US without speaking English. But this means more hiring of immigrant kids, Mormons, etc., not Penn grads.

"An industry full of young, educated, urban progressives, ...American journalists are ... left-wing."

As a claim about individual journalists, this seems broadly true, for the demographic reasons you cite.

"The media is on the left...it’s precisely because the media tends to be left-wing that the media tends to focus on ideas that divide Democrats...."

As a claim about an industry, i.e. the media, this seems broadly false. "The media" is not equivalent to a bunch of cub reporters: it is the owners of Sinclair and Fox, as well as the owners of the Wall Street Journal and NYT, all of them much further right than their employees.

The WSJ is a good example: it's reportage has generally been excellent, while it's editorials have generally been laughably bad. It's clear which of these is the journalists and which is the owners. But which is "the media"?

To make the point about journalists that you want to make, references to "the media" obscure more than they clarify.