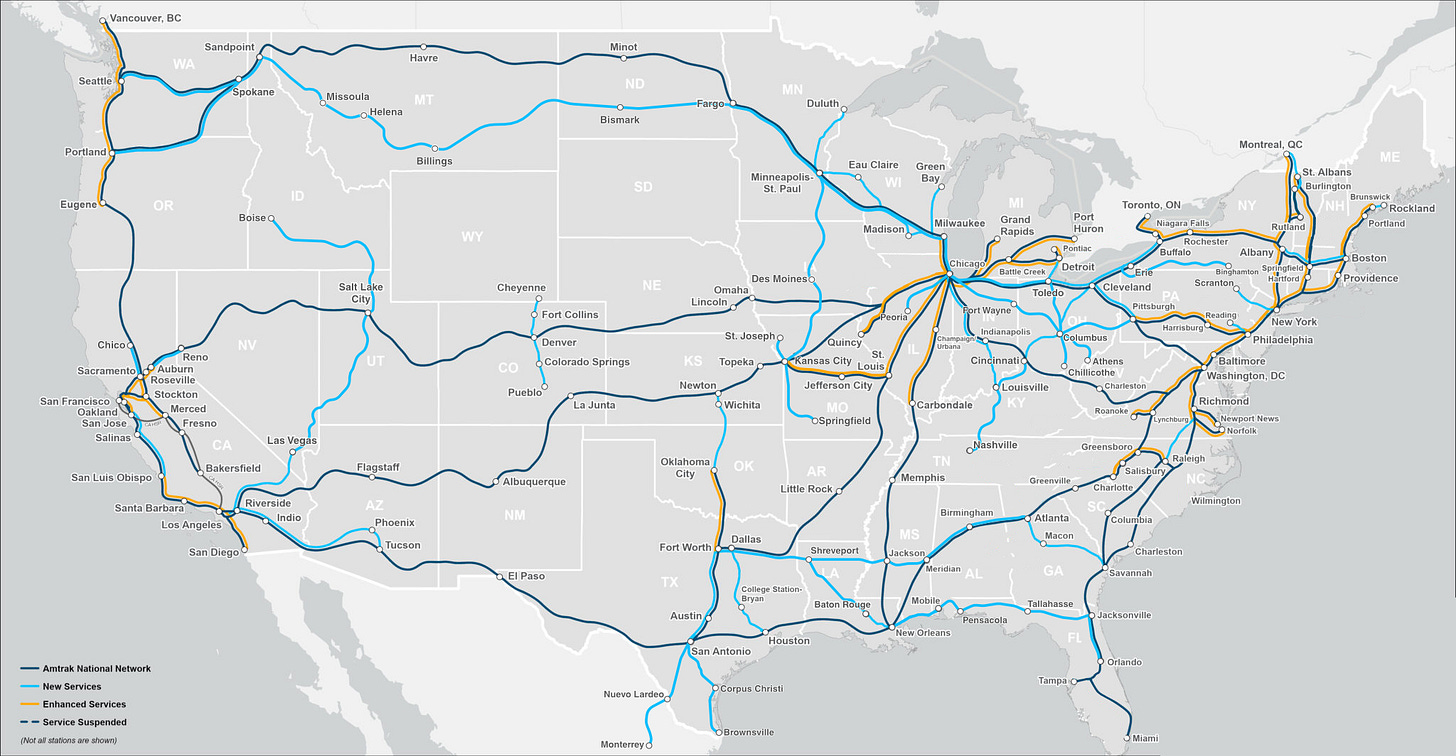

Amtrak released their new vision for passenger rail expansion in the United States, and I don’t really know what to say except that it sucks. They’re proposing incremental expansion of a national network of slow, infrequent trains that I guess will serve the needs of weirdos and hobbyists who want to ride a train from Birmingham to Shreveport or from Athens to Fort Wayne via Columbus but serves no particular transportation purpose.

I get the politics of this idea — spreading a lot of money around to a lot of different places and making modest upgrades to existing legacy rail lines and thus avoiding any difficult engineering problems or potential land use conflicts.

But it’s sad, and I really think Amtrak should be doing basically the reverse. They should draw no new lines on the map, but instead invest meaningful money in building true high-speed rail infrastructure along one of the best high-speed rail corridors on God’s green earth, connecting Washington, D.C. to New York and Boston via Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Haven, and Providence.

I was looking into some potential future travel in France, a country that’s put a lot of money and engineering resources into high-speed rail as a national project, and I was struck by how bad the underlying population geography is. One problem is that outside of Paris, none of France’s cities are really all that large. But also, France is sort of a pentagon with Paris in the center, whereas the whole deal with trains is that they work best in straight lines. If Paris, Rennes, and Bordeaux were all in the same direction that might be a great train route, but as things stand it’s all pretty marginal.

The exception to that is, naturally, the route that goes from Paris to Lyon and then on to Marseille. And the planned extension from Lyon to Turin and then Milan seems quite promising.

Italy itself, though less train-famous in America than France, has much better geography, with a Turin-Milan-Bologna-Florence-Rome-Naples route linking its first, second, third, fourth, seventh, and eighth largest cities. Hooking France into that with the Lyon-Turin line seems like a good idea, though I imagine it’s also very expensive to build through those mountains.

But I was thinking about this mostly because it reminded me of how annoying it is that the United States is stuck between perpetually debating railfan fantasy maps and naysayers talking about how most of the country is too sparse for rail, when the truth is that a small portion of the USA should be one of the world’s great high-speed train markets. I refer of course to the Northeast Corridor, whose incredible potential is cast into stark relief by the success of the relatively unpromising Paris-Lyon-Marseille line.

Big cities on a straight line

Paris, Lyon, Marseille.

Paris has a metro area population of about 13 million people. The New York MSA, by contrast, has about 20 million people. Just because New York is 54 percent larger doesn’t mean you’d expect it to generate 54 percent more trips, since part of the metro area being so huge is that a lot of people don’t live even remotely close to the train station. Still, you can offset that partially by having a separate station in Newark to serve North Jersey customers. The point, at any rate, is that New York is bigger than Paris.

Then you’ve got Lyon in the middle with about 2.2 million people, compared to roughly 6.6 million across the Philadelphia metro area. Again, Philly doesn’t necessarily generate triple the traffic of Lyon, but it does mean the area can support a second station in Wilmington to serve a broader range of people. The point is Lyon is much smaller.

Then at the southern end is Marseille with a metro area population of about 1.9 million people, somewhat smaller than the 2.8 million strong Baltimore MSA. The TGV line also serves Avignon, which is about the size of the Trenton/Princeton MSA.

So basically we could connect a city that’s 50 percent larger than Paris to a city that’s triple the size of Lyon, to a city that’s 50 percent larger than Marseille. Now sure, our mass transit systems aren’t as good. Still, Philly and Baltimore are not exactly poster children for American sprawl. These are real cities with centrally-focused destinations and transit and cabs and people walking around. And New York to Baltimore is only 190 miles versus 480 miles from Paris to Marseille. When you’re going really far, airplanes dominate trains because they move faster. But on shorter trips, the fact that you’re not wasting all this time on airport nonsense makes trains more appealing. Good, fast trains win the bulk of the market share on the Marseille-Lyon-Paris route these days, so the much shorter journeys south of New York are a no-brainer for trains.

And doing these direct city-to-city comparisons doesn’t even take into account that there’s actually a fourth metro area (D.C.) just 40 miles south of Baltimore that’s slightly larger than Philadelphia. So you actually have a city that’s 50 percent larger than Paris (New York) connecting to a city that's triple the size of Lyon (Philadelphia) connecting to a city that’s more than triple the size of Marseille (D.C.). You then get all the connections to and from Baltimore — a metro area that is larger than the second-largest metro in France — for free. This “for free” point is important to the logic of rail. When you have a really strong initial segment, then incremental expansions of that segment can piggyback on what you already built.

To Boston and beyond

To the north of New York, Boston (4.9 million) is bigger than Lyon. Providence (1.6 million) is smaller than Marseille, but New Haven is bigger than Avignon. So while NYC-New Haven-Providence-Boston isn’t nearly as good as the southern leg, it’s still decent compared to the French corridor. But what makes it really great is that you get the connections to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and D.C. for free.

With today’s Northeast Corridor service, taking the Acela from D.C. to Boston is something only someone with a serious fear of flying would do. And even though taking the train to New Haven is objectively the best way to get there from D.C., it’s a pain in the butt. But at true high-speed rail speeds, the Boston-D.C. trip would take about the same time as Paris-Marseille. So all these trips — D.C. to Providence, Baltimore to New Haven, Boston to Trenton — are very feasibly made by train. And again, while it’s certainly true that France outperforms the United States at small-city mass transit, we’re mostly talking about cities with strong centers and moderately difficult parking.

Now what’s intriguing is you could potentially extend this logic in the other direction.

A train from Virginia Beach (1.7 million people) to Richmond (1.2 million people) and then to D.C. is not that compelling. The good news is the distance involved isn’t huge, so the cost wouldn’t be enormous. These cities aren’t very large and they are pretty sprawly. But they would also get the connections to Philadelphia and New York and even points north for free. That’s potentially pretty compelling. And then the same thing applies as you consider extending from Richmond to Raleigh and Raleigh to Charlotte, and then next thing you know you’re going to Atlanta.

If you just go by the numbers, D.C.-Richmond-Raleigh-Charlotte-Atlanta could work. D.C. is smaller than Paris, of course, but Atlanta is much bigger than Lyon and Charlotte is bigger than Marseille, and you’ve also got Richmond and Raleigh in there. Now does anyone actually want to take a train to or from cities with the urban form of a Charlotte or a Raleigh? I’m not sure. I would expect them to underperform French cities based purely on population. But by how much do they underperform? Because even if this leg underperforms Paris-Marseille, it benefits from the northern connections to Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. Yes, only psychos would want to take even a very fast train from New York to Atlanta. But the evidence from Japan is that a nonzero share of the population is psychos and New York and Atlanta are very large cities, so it adds up to more than nothing, especially if you get it for free.

You can see a lot of mathematical modeling of this southern leg from Alon Levy here, and their model (which is trained primarily on European data about population, distance, and ridership) suggests that D.C. to Atlanta pencils out surprisingly well precisely because of the free northeast corridor. Now I want to flag here that Alon concedes that sunbelt cities would probably underperform this model due to sprawl. They’re obviously right about that; the only question is exactly how big the underperformance is. The reasonable thing to do would be to build to Richmond and see what happens. I’m skeptical that the bigger project would pan out, but in this case, it would be worth trying the small extension just to see.

Northeast HSR would improve aviation

Even if a D.C.-to-Atlanta train worked great, it wouldn’t necessarily accomplish anything transformative.

One reason the core Northeast Corridor train project would be so valuable is that not only would a lot of people use it, but building it would strengthen America’s passenger aviation system. Right now there are three airports subject to FAA slot controls due to capacity constraints — JFK, LaGuardia, and DCA. There are also four airports under a soft control system — O’Hare, LAX, SFO, and Kennedy.

There are currently 34 flights per day from DCA to Boston and seven to Providence. There are 19 flights from JFK to Boston, eight to DCA, and three to Baltimore. There are 24 flights from LaGuardia to DCA. Replacing a large fraction of this intra-northeastern flying with train trips isn’t just some dopey railfan fantasy, it would let these crowded airports offer more flights to other destinations.

This is another part of the story where the fact that New York is quite a bit larger than Paris becomes relevant. France is aiming to eliminate short-haul domestic flights in favor of train trips as an ecological matter. That’s a nice idea, but also a bit eccentric. The New York version of this is more down to earth. More people want to fly into this giant city than its airports can accommodate, and there’s no good way to expand the airports. But the world has the technology to make train trips from New York to elsewhere in the northeast very fast and convenient, which would let the finite airport capacity be used to take people to Memphis or Minnesota or Missoula or wherever else.

And again, the core system is so good that it at least might allow for significant further expansions. By the numbers, NYC to Toronto via Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo could work. And in a world where people are taking the 3:20 train ride from Toronto to New York, there are also people taking the 3:25 ride from Syracuse to D.C. or the 3:05 ride from Rochester to Philadelphia that you get for free. The availability of those freebies strengthens the case for New York-Toronto (a pretty good transit city) which, again, relieves the airport congestion. Levy, feeling expansive, thinks there’s even a case for a line that would go from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, which because the Northeast Corridor already exists, lets you get from Pittsburgh to New York in 2:30 or from Pittsburgh to D.C. in 3:05. Once that exists you can extend to Cleveland, which reaches New York in 3:10. This is a bit marginal, but the power of going all the way to Cleveland is once you’re there, a modest Cleveland-Toledo-Chicago segment also gets you Chicago-Pittsburgh in 2:30 and Chicago-Philadelphia in 3:40 for free.

As with the southern extension to Atlanta, I don’t know if those midwest routes would really pan out. You’d want to use Richmond as the test case for travel demand outside of the northeast. The point I want to make is that the case for the core Northeast Corridor route is very strong, and the case for other routes is much stronger if the fast Northeast Corridor already exists. If you want to build high-speed rail from Chicago to Cleveland, the best way to do it is to have a strong Northeast Corridor in place first.

We need proposals that make sense

Back to the map of France. While Paris-Lyon-Marseille makes perfect sense on its own merits and the route from Paris to Lille facilitates important international connections (the Chunnel to London and the Thalys to Brussels), the routes in other directions are mostly about covering the whole map in a way that’s fair.

This is not ideal for France, as very few people live in Le Mans or Rennes. But the country isn’t all that big, so if some wasteful lines get built, it’s not the end of the world.

The United States, by contrast, is gigantic, so if you just start drawing lines on a map for fun, you come up with things like trying to route multiple lines through the vast empty spaces surrounding Denver or the idea that there is so much demand to go to Columbus, Ohio that it warrants multiple redundant high-speed connections between Pittsburgh and Chicago.

Amtrak is, I guess, pragmatic enough to see that nobody wants to build a dedicated high-speed rail line from El Paso to Albuquerque. But they do want lots of lines on the map. So we get these proposals to re-activate passenger service on all kinds of existing freight rights of way. The problem with that is it’s way too slow to compete with flying, and it doesn’t make sense as an alternative to a long drive if you’re going to need a car when you get to your destination anyway.

We need something much smaller and more focused but much better in terms of the actual quality of the transportation service offered — something that could run frequently, attract lots of riders, and help ameliorate the real problem of NYC aviation congestion. You can sort of see why the federal government doesn’t want to fund such a geographically focused project. On the other hand, I don’t think Amtrak’s strategy of acting like a giant pork barrel program is actually very successful in securing support for the railroad. It’s true that finding financial and political support for a technically sound high-speed rail proposal would be challenging, but the potential benefits of a plan that makes sense are actually very large (and not truly limited to the northeast), so they’d have a fighting chance. And if they fail, at least they’ve failed at something that would have been worthwhile.

Pete Buttigieg has been a disappointment as Secretary of Transportation. If smart, young technocrats we’re good for anything, it would be lowering construction costs. He seems to have done zero on that front. He hasn’t even done a symbolic house cleaning at Amtrak. Google him and you’ll see he recently visited a UPS facility and has been active talking about LGBT rights.

This is very sad because his incentives are almost perfect. He will never win a statewide election in Indiana. His only viable paths are moving to a different state or running for President or Vice President. Cutting through red tape and bashing entitled bureaucrats to build eco-friendly rail and mass transit would be a great strategy for capturing the vital center. And yet this extremely disciplined, smart dude hasn’t made any changes that matter.

As Yglesias has written before, [1] the issue is Amtrak leadership.

> I sometimes like to tell the story of the time an Amtrak executive told me “to be honest, I don’t know that much about trains.”

> And I think this is emblematic of Amtrak. It is run by people who are not curious about trains.

A leadership shakeup is needed to address these issues. The suggestion in that earlier article is to bring in a foreign CEO who has experience in running a functional rail system. E.g., someone from the rail programs of France, Italy, Japan, Korean, etc.

But there just isn’t the political will to fix Amtrak leadership and there are existing constituencies that benefit from the current pork barrel approach.

[1] “Amtrak should bring in foreign experts to make trains great again”, https://www.slowboring.com/p/amtrak-should-bring-in-foreign-experts

*Edited to fix typo