Americans have been gaining weight for as long as records exist

There's no need for a big obesity whodunnit

Fresh episode of “Bad Takes” is out today, and this time it is actually on a related subject! We’re talking about the new childhood obesity guidelines and the backlash to them.

In reading about obesity recently, I’ve noticed that conventional wisdom seems to have settled on the idea that there was a sharp uptick in obesity starting around 1980.

That’s kind of an odd thing, and it has understandably led a lot of the people writing about it to view obesity as a puzzle to be solved.

There’s a fascinating and highly readable series of posts on the Slime Mold Time Mold blog that’s very explicitly written as a kind of whodunnit (“the study of obesity is the study of mysteries”) that eventually points the finger at chemical contamination via lithium. It’s a pretty niche theory and appears to be based in part on several factual errors about wild animals and the relationship between altitude and adiposity.

But as with any great mystery, there are rival theories. One that’s gotten very popular on the internet right (though there is prior art from Mother Jones on the left) points the finger at “seed oils.” The idea here is that the American diet has been wrecked by the deviation from traditional animal-derived cooking fats to non-traditional cooking fats manufactured from various kinds of seeds. The seed oil theory is something of a successor to the (mostly leftwing) concern about “trans fats” that popped up 10 to 20 years ago.

Another common theory blames… public health advice.

After all, it was in 1980 that the government officially recommended a low-fat diet — advice that almost everyone now agrees backfired and encouraged the consumption of low-nutrition, low-satiety carbohydrates as people told themselves that foods full of added sugar were healthy because they were low in fat.

I think the entire premise of a mysterious obesity inflection point around 1980 is probably wrong. The whodunnit is a classic genre, and if you’re trying to create compelling content, it makes sense to twist your nutrition narrative into that shape. But the evidence suggests a much more boring story about a long-term increase in average weight punctuated by the Great Depression and World War II. And this in turn suggests that there probably isn’t some unitary big bad we can blame so much as a broad tendency for food to be cheaper, more widely available, and tastier, which is a situation with a lot of virtues but also some downsides. I do not (yet!) have a bestselling book promising solutions to all this, but I do think it would probably be helpful to start with a more realistic baseline.

Weight gain over the long term

The framing of a relatively sudden and recent shift is widespread. A 2016 CBS story, for example, says “The average Americans' weight change since the 1980s is startling.”

And it is pretty startling. Of course, as with a lot of slightly misleading popular narratives, you’ll note if you read the article that it’s not like it explicitly denies that there was startling weight gain prior to 1980. It just doesn’t address the issue, in part because it’s harder to find nationally representative data the further back you go. But the data we do have suggests that this is not a recent phenomenon — weight change since the 1880s is also startling.

It’s helpful to consider the context of the pre-1980 period. The median age in the United States in 1960 was 29.5, which fell to 28.1 by 1970 before rising again to 30 in 1980. This is to say that the population didn’t age at all over this 20-year span. By contrast, since 1980, the median age has risen steadily to 32.9 in 1990, 35.3 in 2000, 37.2 in 2010, and 38.6 in 2022. Population aging has a mechanical impact on average obesity that is unrelated to changes in diet and nutrition.

John Komlos and Marek Brabec explain in their paper on the evolution of BMI values that the 1980 discontinuity arises because of studies that “do not look at birth-cohort effects — that is, the evolution of weight among people of the same birth year.”

They present this terrible-looking chart of BMI deciles, not over time but across birth cohorts. It shows that people born in 1900 were heavier than people born in 1880 and that people born in 1920 were heavier than people born in 1900 and so forth. They also show a lot of dispersion in body-mass index across birth cohorts. The top 20 to 30% of the population has gotten dramatically heavier, while the bottom 20 to 30% percent has gotten only slightly heavier. The bottom 10%, notably, has gone from being underweight on average to being healthy. People born in 1880 were thin, but that wasn’t necessarily good news.

They back this up with a nicer-looking chart using some older and less representative data from new cadets at West Point and The Citadel in South Carolina. They show that Citadel cadets born in the late 19th century were a full 7 kilograms lighter than those born in the interwar period, and that West Pointers born in the mid-19th century were even slimmer than those citadel grads.

Both charts show a slowdown in average weight gain around the middle of the 20th century. This is not surprising — there was a global economic crisis and a war that produced the last historical famines in Europe during this period (I recommend Cormac Ó Gráda’s book “Famine: A Short History”). Wartime conditions in the United States were much more comfortable than those in Greece or the Netherlands, but even we were rationing food. Then after World War II, the Baby Boom introduced another confounding factor to national weight statistics.

But the basic story is that in birth-cohort terms, people have been adding weight as far back as our high-quality data goes, and lower-quality data suggests they were adding weight before that, too.

More data on this

Despite my reputation, I hate being called a contrarian — so to be clear, the Komlos and Brabec paper is not the only source pointing to long-term weight gain.

Dejun Su compares the weight of U.S. Civil War draftees to American men in the early 1970s and, while this isn’t the primary finding of the paper, notes a huge increase. Max Henderson, likewise, notes briefly that men in the 1971-1975 NHANES I study are much heavier than Union soldiers, although the point of the paper is to do some complicated math about mortality risks. The bare fact that there was substantial weight gain pre-1980 doesn’t even seem remarkable enough in this subfield to be the subject of a paper.

Scott Allan Carson, looking at 19th-century data, also finds people were much slimmer back then. His key finding is related to higher BMIs among farmers in the 19th century, which he argues is because they had better access to food than tradespeople and urban workers.

Again, not to be too contrarian about this, but one reason for the focus on the post-1980 trend is that the rise of the “obesity problem” genuinely is very new. Carson isn’t finding that farmers were problematically fat and urban workers were hale and hearty, he’s finding that urban workers had serious food security issues while farmers had routine access to nutrition. The shifting population age trends can distort our understanding of aggregate national statistics. But from a “what should we be talking about as a society” lens, the fact that society in 2022 is much older than it was in 1982 is a genuine change, not a statistical illusion, and it’s totally reasonable to be paying more attention to the health problems this shift brings.

In 1969, Richard Nixon hosted a White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health. This was kind of a triangulation effort to steal thunder from Bobby Kennedy’s famous Appalachian rural poverty tour, which itself built on work in Congress by Bob Dole and George McGovern on nutrition. But what all these people — Dole, McGovern, Kennedy, Nixon — were talking about was hunger. Nixon vowed to “put an end to hunger in America for all time,” and this late-60s discourse itself came after a good deal of earlier policymaking in the hunger space. Richard Russell and the Truman Administration created the federal school lunch program in the 1940s, and SNAP goes back to congressional politics in the 1950s and some JFK executive orders before really expanding as part of the Great Society.

And this all basically worked to the extent that nowadays we tend to focus on food insecurity — a different standard reflecting a more affluent time. A household qualifies as food insecure if they “obtained enough food to avoid substantially disrupting their eating patterns or reducing food intake by using a variety of coping strategies, such as eating less varied diets, participating in Federal food assistance programs, or getting food from community food pantries.” This is just to say that food insecurity doesn’t mean people are going hungry despite efforts to provide help — it’s defined such that the people getting the help are by definition food insecure.

The point here is that the Diet Detectives have taken a true fact (obesity only emerged as a significant public health concern during the 1980s) and turned it into a puzzle (why did weight suddenly increase after 1980?) when everyone who’s looked into long-term trends seems to find broad continuity in weight gain. For example, even without the cohort analysis, you see a decline in the share of underweight Americans during the 1960s and 1970s:

Seen in this light, I think the puzzle is a bit less interesting. Why have Americans been steadily gaining weight, except when interrupted by depression and war? Because we like food and we’re getting richer.

It’s easier to get food

I’m not going to offer a comprehensive theory of obesity and nutrition policy in this post. Suffice it to say that for the overwhelming majority of human history, food insecurity — occasional bouts of not having enough food to eat or needing to change eating patterns due to lack of money — was incredibly common.

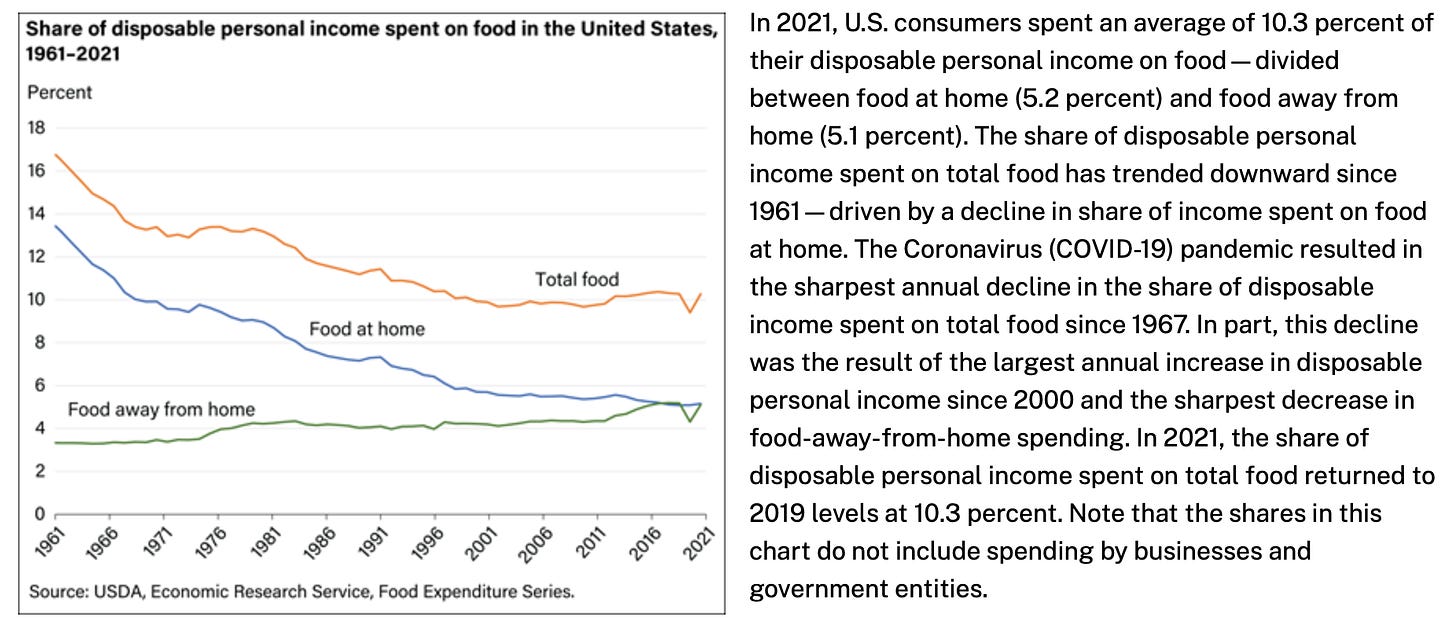

One of the great privileges of living in one of the wealthiest societies the world has ever known is that spending on groceries has plummeted as a share of household spending. It’s plummeted so fast that aggregate food spending has fallen a lot even though people dine out more.

The food is also (and relatedly) better across many dimensions of betterness.

That’s true, of course, of the much-deplored ultra-processed junk food, created by skilled scientists who labor to make tastier and tastier concoctions with which to tempt us. But it’s also true that in 2023, you can get pretty good Thai food in Blue Hill, Maine and okay sushi in Kerrville, Texas in a way that wasn’t true in 1993 and certainly wasn’t true in 1973. When I was growing up in Manhattan, we did have Thai restaurants and sushi (very cosmopolitan!), but we didn’t really have avocados in the supermarket and all the Mexican food was terrible. Within the fast food space, we now have Shake Shack and Chipotle, not just McDonald’s and Taco Bell. I had a delicious Sichuan meal one time in Cleveland.

You also see this, though, in home cooking.

Here’s a great Kenji Lopez-Alt recipe for beef stew, for example, in which he explains that “I’ve started making my stews with two different batches of vegetables.” One batch of vegetables goes in with the meat for a long cook to produce a flavorful stew broth. But then those vegetables are discarded and replaced by a second batch of vegetables that were brown separately and then added to the stew shortly before it’s done cooking. This gives you the rich flavor of the long-cooked vegetables in the broth, but the actual vegetables that you eat are perfectly cooked rather than overdone.

Your grandmother would have found this advice insane because you are literally throwing away food, and the point of a stew is to be cheap. But while we continue to enjoy many cucina povera dishes, we’re mostly not actually desperate to minimize our spending on raw carrots and onions — we want to know how to make the best stew, not the cheapest stew.

In today’s more affluent society, it is much less common to need to choose between going hungry and eating something you don’t like. The vast majority of Americans on the vast majority of days have access to food that we subjectively enjoy, and we also have the opportunity to rotate through foods if we get bored of them. If you focus narrowly on the subset of food that is “junk,” “fast,” or “ultra-processed,” then you can make this out to be a bad thing. But it’s really true across the whole spectrum of culinary experiences, and the change has been occurring steadily for as long as we’ve had modern economic growth.

It just turns out that like a lot of things, this has some downsides. The question of what, if anything, to do about those downsides seems pretty difficult to me, but I don’t think its origins are a big causal mystery.

If anything, making the origins out to be some huge puzzle lends itself to the false suggestion that there’s a very simple and straightforward solution. The truth — that we are experiencing some downside to living in a society with a great deal of material abundance — is harder to wrestle with, since people would be pretty unhappy about policy changes that reversed the 100+ year trend toward food becoming tastier, more available, and more convenient.

"The seed oil theory is something of a successor to the (mostly leftwing) concern about “trans fats” that popped up 10 to 20 years ago."

That's a weird spasm of both-siderism on your part, Matt.

The campaign to reduce trans fats was not primarily directed against obesity but rather against heart disease, because transfats have an outsized impact on atherosclerosis, I.e. the deposition of fatty plaques on coronary arteries.

And so far as I know, the research that showed that transfats caused greater atherosclerosis was extensive, solid, and still holds good today.

So: you are comparing speculative, YouTube conspiracy theories about "seed oils" making us obese, to well -established research showing that trans-fats cause heart disease, all so that you can say, "the leftwing does it too!"

Not good.

I like to think of how each decade’s reputation is really just about baby boomers’ point in their life (50s idyllic boring suburb life, 60s a time of discovering drugs and sex and music, 70s partying a bit too hard, 80s time to make money) and adding in the 80s/90s oh no we’re gaining weight in our 30s and 40s is funny to me.